When Stuart Robertson, a marketing executive with the England and Wales Cricket Board, conceptualised T20 cricket, the idea was to do away with the mundane traits of ODIs to get the crowd back to the grounds.

Till the early 2000s, ODI cricket provided the thrills mostly for 20 overs out of the 50 that made an innings — the first 15 overs when the openers went berserk with the advantage of the fielding restrictions and the last five overs when the urgency to stretch the team total kicked in with batters throwing their bat at almost everything. If the batters failed, the bowlers struck.

But the middle phase — 15 overs to 45 overs — was often spent in batting teams accumulating runs in singles and twos and bowling teams trying to dry them up. That was the script more or less. Robertson detected the problem and suggested that the middle bit be chopped off. That gave birth to T20 cricket and the rest, you like it or not, is history.

Purists feared that 20-over cricket would annihilate the 50-over game. But ODI cricket, which was first played in 1971 as a replacement for a washed-out Ashes Test, has survived and we are just a couple of days away from yet another 50-over World Cup.

Following the trend

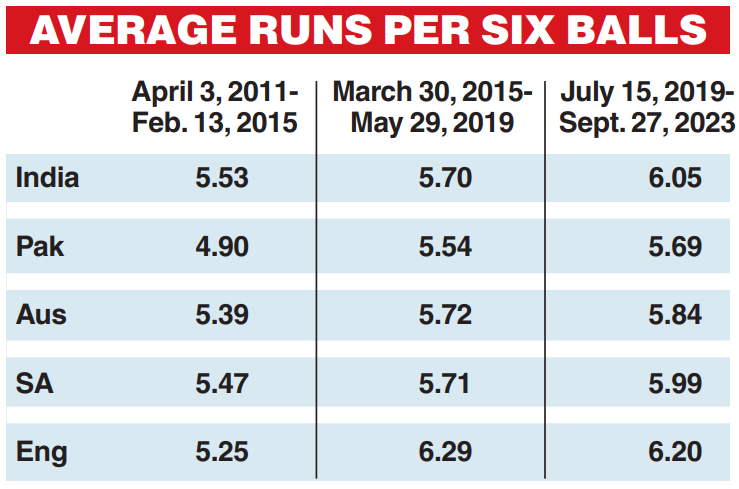

What has one-day cricket done to keep itself afloat? To simplify the answer, it has been trying to reinvent itself in a T20 mould in order to do away with the “boring” tag.

Look at these numbers — 392, 338, 416, 315. They were the totals of the team batting first in the recent South

Africa-Australia ODI series. Four out of the five matches saw 300-plus scores, that too with two top-bracket teams competing.

In the 2011 World Cup, which was co-hosted by India, there were only two matches where 300-plus totals were made batting first with two traditionally stronger teams competing against each other — the India-England and Pakistan-New Zealand games. The rest of the matches which saw 300-plus scores involved either Bangladesh, Zimbabwe or an associate nation. Mind you, a total of 49 matches were played in that edition of the World Cup.

One isn’t saying that the upcoming World Cup will see a flurry of 300-plus scores, because the varying playing conditions in a vast country like India will surely come into play when the teams devise their strategies. But whatever the overhead and under-the-feet situation, one can rest assured that the teams will seldom go into a shell. That’s because, thanks to T20s, the mindset of playing an ODI has changed.

Game of chase

Most of the current generation of cricketers have grown up feeding on T20 cricket, sometimes an overdose of it, and therefore consciously or subconsciously they play their cricket, even Tests, with an aggressive touch. And the authorities too pamper such an approach because that attracts eyeballs and advertisers.

So the T20-isation of ODI cricket is in full swing, be it technique or tactics.

There was a time not too long back when posting a 300-plus total would almost guarantee a win. Not anymore. And a team doesn’t have to belong to the elite club to have that confidence that any total is chaseable. The Netherlands almost chased down a 375-run target in a World Cup Qualifier match against the West Indies earlier this year. The scores were tied before the Dutch won via the Super Over.

Commentators and experts nowadays seldom ask captains what is a safe score.

It is no coincidence that of the ten 200-plus individual scores that are there in 50-over cricket, none have come before 2010. Six of them have come after 2015 or later, the period which can easily be called the T20 era with tournaments like the IPL and Big Bash gaining unprecedented popularity and acceptance.

It’s shrinking, but...

It is no surprise then that often selections for ODI national teams are made evaluating the players’ T20 form. No, no selector will ever say that on record, but whatever is unsaid is not necessarily untrue.

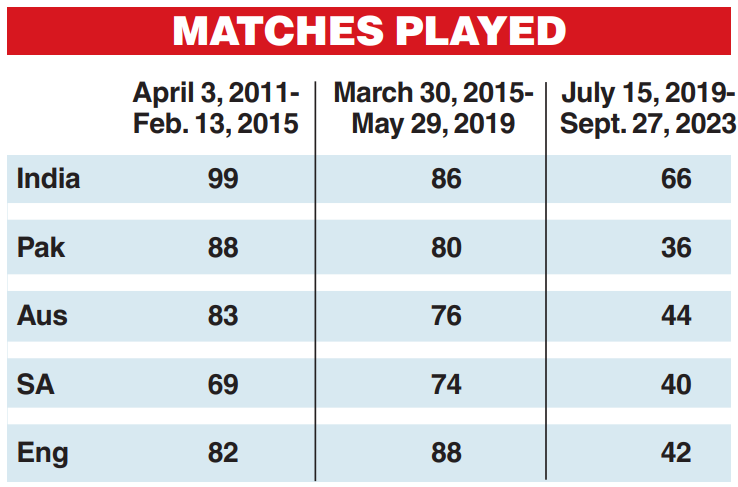

But that to some extent is also unavoidable with the teams playing lesser number of bilateral ODI series nowadays. The tri-nation or quadrangular meets are also a thing of the past. The bilateral engagements are either

Tests, because the red-ball contest is still a matter of prestige and honour, or a bouquet of T20s which interests fans of all ages.

The impact of T20 cricket in the 50-over white-ball game is not restricted to batters unleashing outrageous shots and teams piling mountains of runs. What about the slower bouncers? Or the relay-catches at the boundary? They all are T20 imports.

So does all of the above mean that the upcoming month-and-a-half-long 13th ODI World Cup will just be a glorified version of the IPL? Maybe not. The varied challenges of Indian surfaces and conditions might just force teams to be a little more old-fashioned than they usually are. If that happens, ODIs might save itself from being just a part-time exercise in between T20 extravaganzas. The thrill is not necessarily only in the swing of the bat.