Given that the BCCI recently announced prize money of Rs 1.25 crore for Indian curators and groundsmen at the conclusion of the IPL, lauding them as “unsung heroes”, it is worth pointing out that this year’s Wisden carried an article, “The pitch debate”, by Andy Bull, a senior sportswriter for The Guardian.

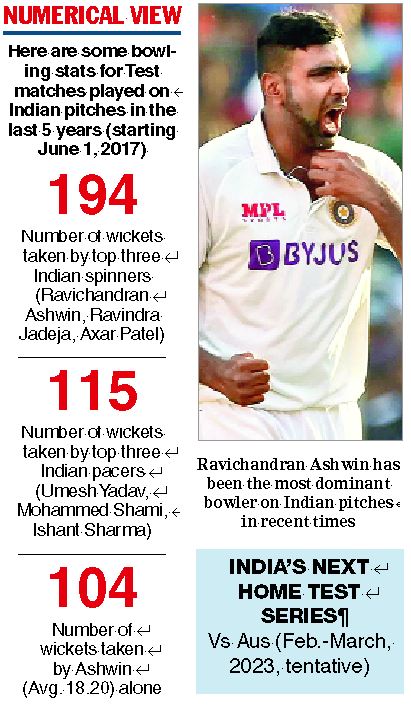

Basically, India has long been accused of producing dust bowls on which its spinners can wreak havoc against visiting Test sides. Joe Root has been replaced by Ben Stokes as England captain but the former did hint his side would get its own back when India toured his country.

With James Anderson and Stuart Broad back in the England side (after being dropped during the tour of the West Indies earlier this year), it can be assumed groundsmen at Edgbaston will prepare a pitch suited to them when the fifth Test against India left over from last summer is played at Edgbaston from July 1-5.

The series was left 2-1 in India’s favour so things did not turn out quite as Root had hoped. It has generally been accepted practice for groundsmen to prepare pitches that favour home sides, not least in England.

Bull’s Wisden article is not entirely unfriendly to Indians but he refers to “the row that broke out during the tour of India in 2020-21. After a handsome victory at Chennai, England were badly beaten on spinning pitches in the next three matches.”

He adds: “The low point came in the Third Test at Ahmedabad, where India won inside five sessions, and five spinners took 28 of the 30 wickets. England’s players kept their own counsel, though Joe Root hinted at his feelings when he said India would face ‘really good pitches’ on their return tour a few months later. Some of his predecessors as captain were blunter. ‘Tough to watch’, said Alastair Cook; ‘awful’, said Michael Vaughan; ‘a lottery’, said Andrew Strauss.”

Bull goes on: “India’s response was led by India’s off-spinner Ravichandran Ashwin, who had taken seven of those 28. When an English journalist asked him if it had been ‘a good pitch for Test cricket’, and whether he wanted ‘a similar surface in the next match’, Ashwin replied with questions of his own: ‘What is a good cricket surface? Who defines it?’ The journalist suggested a balance between bat and ball. Ashwin agreed, then repeated his questions.”

Bull says: “Of course, they were rhetorical: it is the ICC who define the quality of a pitch, on a scale ranging from ‘very good’ to ‘unfit’. And Ashwin was familiar with their criteria. As he put it: ‘Seam on the first day, then bat well, then spin on the last two days?’ It wasn’t far off: the ICC’s pitch-monitoring tool defines a ‘very good’ pitch as one which offers ‘good carry, limited seam movement and consistent bounce throughout, little or no turn on the first two days, but natural wear sufficient to be responsive to spin later in the game’.”

In marked contrast, “a ‘poor’ pitch offers either ‘excessive seam movement or unevenness of bounce at any stage, excessive assistance to spin, especially early in the match, or no or little seam movement, spin, bounce or carry’.

The idea is to provide ‘a balanced contest between bat and ball over the course of the match, allowing all the individual skills of the game to be demonstrated at various stages’. In short, a pitch should do a little of everything, and not too much of anything.”

Bull then poses the question: “How much is too much? It depends what we understand by ‘excessive’ — which means the regulations are, in effect, a more complicated version of that single word used in 1727: ‘fair’. The interpretation is so loose that only one international pitch in the last four years has been rated poor: the Wanderers at Johannesburg in January 2018, when the umpires ended play 20 minutes early on the third evening after South African opener Dean Elgar was hit under the grille by India’s Jasprit Bumrah. Even South Africa didn’t try to defend it. The Ahmedabad pitch, on the other hand, was rated average.

“If the regulations read like an attempt to please everyone, it may be because everyone wants something different. Fast bowlers want pitches to be hard and green, slow bowlers dry and dusty, batsmen true, chief executives durable, spectators entertaining, and coaches whatever gives their team the best chance. Groundstaff, you suspect, simply want the critics off their back.”

Bull concludes: “And that’s what Ashwin seemed to be getting at. There was a lot to unpick in his exchange with the journalist, since the question implied India had fixed the pitch to suit their strengths, produced a surface so tricky for batting it resulted in a game of chance, and robbed spectators of over three days of cricket. His answer came across as a challenge to the moral authority of the English, and tapped into old charges of arrogance, exceptionalism and hypocrisy. Simmering beneath was the idea of fairness: how far it stretches, who defines it.”

One way and another, these are testing times for pitches, especially the ones prepared for five-day international games in India.