Orthopaedic surgeon Sivaraman Arumugam is willing to bet that cricket fast bowlers under training in Tamil Nadu will soon have an edge over their counterparts elsewhere in India — unless other states too adopt his centre’s “protocol.”

Promising fast bowlers under the watch of the Tamil Nadu Cricket Association are set to be offered a biomechanics-based strength and conditioning protocol designed to minimise their risk of injuries, enhance their performance and prolong their cricket careers.

The protocol — a tailored set of exercises to strengthen the lower back — is the outcome of a study of fast-bowling biomechanics conducted by Arumugam and his colleagues at the Sri Ramachandra Centre for Sports Science, Chennai.

While bowling overload — the repeated hurling of a ball over months to years — contributes to the risk of injury, earlier studies have also suggested that the mechanics of fast bowling critically influence the performance and the level of this risk.

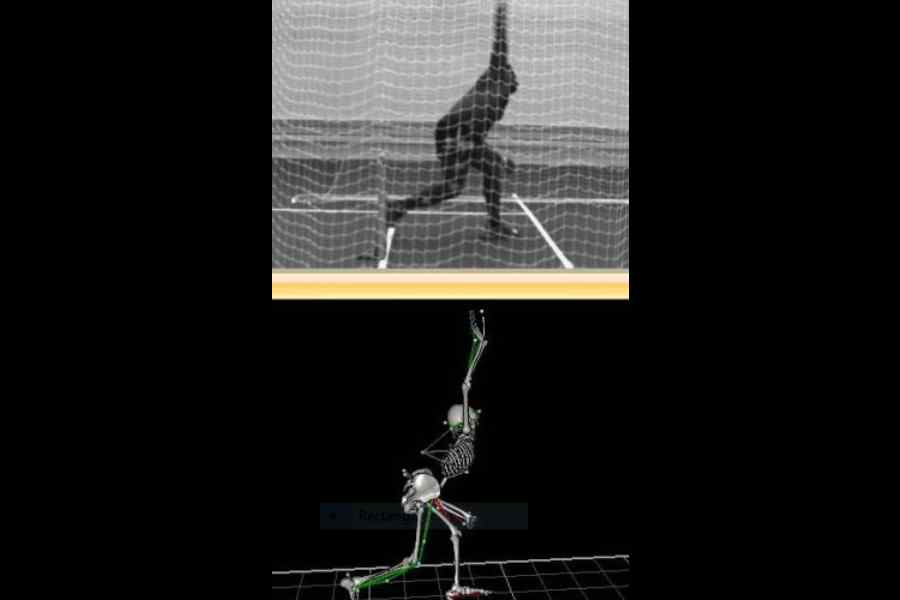

Arumugam and his colleagues invited state-level fast bowlers from Kerala and Tamil Nadu into their biomechanics lab and measured three risk factors for lumbar spine injury — their sideward bending angles, the knee rotation angles, and the peak vertical ground reaction force when throwing the ball.

The risk of lumbar spine injury in the bowlers increases when the sideward bending and the knee angles and the peak ground reaction force exceed threshold limits. The Chennai researchers found that one in four bowlers exceeded angle thresholds, while 46 per cent of the bowlers exceeded the peak vertical ground reaction force limits.

The findings implied that nearly half the fast bowlers were at risk of lumbar spine injury.

The researchers, collaborating with experts in Australia and South Africa, designed the strength and conditioning protocol — an exercise regimen including plyometrics, squats, lunges, planks, broad jumps, hamstring curls and back extensions, among others — to lower the risk.

They studied the ball hurling behaviour of 21 fast bowlers who continued with standard practice and training and 21 other fast bowlers who were asked to adopt the protocol for 12 weeks. Those who took up the protocol showed significant improvements in the sideward and knee movements as well as lower peak ground force, decreasing the injury risk.

“As a bonus, after the training, the ball’s speed also increased — the bowlers threw the ball faster under movements that lowered their risk of injury,” said Arumugam. The Tamil Nadu Cricket Association has sought to incorporate this protocol as part of its training programme for fast bowlers.

The Sri Ramachandra Centre for Sports Science has proposed to the Board of Cricket Control of India to consider introducing the protocol in other states. Multiple studies from India and other countries have underlined the risk of lumbar spine injury and its consequences for fast bowlers.

Mandeep Dhillon, an orthopaedic surgeon at the Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, has described the Chennai study as an illustration of how biomechanics can provide insights into the forces generated during fast bowling.

Such information, in turn, can help experts design specific actions to generate more bowling pace while minimising injury risk, Dhillon wrote earlier this year in a commentary on the science medicine of cricket published in the Indian Journal of Orthopaedics.

A study among elite male academy cricket players in England and Wales, for instance, has shown that the lumbar spine was the most common site of injury, making up 15.3 injuries per 100 players per year, followed by the hand (12.1), ankle (11.1), and the shoulder (8.1) and knee (8.1).

The study by Amy Williams and her colleagues at the University of Bath in the UK, published last week had also found that lumbar spine injuries most commonly occurred during bowling. A large proportion of these injuries were stress fractures that typically take four to six months to fully heal.