At first, I thought it was fake news. But soon enough, it became real — gradually, and then, all at once. Football was about to change. Forever. The world’s most powerful clubs had decided that they wanted to create their own paradise. The lesser mortals with whom they had jostled for decades were not invited. The Super League was introduced as a behemoth that would overhaul the sport and herald a fresh dawn. The finances had been secured, the marketing had begun, the muscle power of Europe’s elite was on full display. In the midst of the pandemonium, one stakeholder of the game had been conveniently forgotten. In football’s latest glittering product, there was no place for people like myself, no place for the fans.

A NEW WORLD ORDER

They said they were listening to the fans of the future, who apparently wanted to see Barcelona play Liverpool every second week. They said they were listening to 16-24 year olds, who apparently wanted to see more exciting football, even if that meant less than 90 minutes of action per match. In reality, they, the biggest football clubs on the planet, were only listening to their pockets.

As someone who has followed football religiously over the past decade, I have heard murmurs of discontent at the top before, threats issued by leading clubs to break away. But never could I have imagined that the clubs, each of whom are a global brand, would try to pull off the ultimate sporting heist. And yes, it was a heist; a master plan to uproot the pyramid of football in the middle of a pandemic and concentrate even more wealth at the top, to redistribute even less from the revenue pot, and complete football’s transition into an oligopoly, paving the way for a new world order that only celebrates the rich, the powerful, the sinister.

A HOUSE OF CARDS

A single league where there is no promotion or relegation, no qualification battles for a bigger tournament, no tangible motivation to succeed and no tangible risk to fail is not a sporting face-off, it is an avenue for producing content that overdoses the viewer on all things world-class: players, managers, stadiums, and so-called tussles of the best against the best.

Durga Puja would lose its charm were it to happen every month. The satisfaction of a spoonful of biryani would not be the same were it to be served every night. Similarly, there would be nothing special about watching the best against the best, if the best never squared off against the rest, if there was no underdog to rally behind, no upsets to cherish, no Shakespearean tale of rise, fall, and redemption.

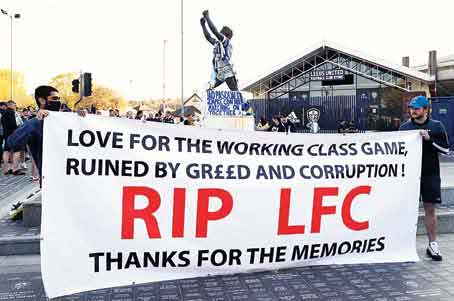

The Super League’s intention to homogenise football and force it into a regurgitating bubble paid no heed to what has kept the game alive for generations of supporters. And once these supporters showed the Super League the red card, it was only a matter of time before this avaricious adventure came to a screeching halt.

Once more, though, the speed of it all left me dazed. Less than 50 hours after the founding members had championed the League, a domino effect kicked in, which saw them leave in lockstep. Like a pack of cards, the Super League came crashing down, its foundations revealed to be even more fragile than the egos that helped erect it in the first place.

THE FUTURE OF FOOTBALL

When the Super League was officially cancelled, I felt as if I had woken up from a nightmare. The relief, however, remains temporary. Football is financially broken, and the spectre of the Super League is bound to return in a more nebulous avatar. Notwithstanding the ceaseless ambition of the big clubs to corner resources for themselves, it is no secret that they are losing money. The depreciating broadcast revenues over the last six or seven years, combined with the devastating economic impact of the pandemic, means that a different financial model is a must.

But that model cannot be the Super League. For such a model only serves to rescue the rich by killing the poor. Fans like myself, who are prone to bouts of sentimental socialism, would probably suggest making all football clubs owned (at least in part) by their supporters, to invite government aid to haul up those at the very bottom, and to create a mechanism for equitable distribution of funds. Yet, deep down, fans like myself also understand that this is asking for too much, yearning for the moon while being scorched on earth.

The final solution that can plausibly propel football forward is one that involves a compromise, between the mercantile interests of the “dirty dozen” (a coinage referring to the founding members of the Super League) and the survival instincts of the remaining field. This compromise can come about through fine-tuning current tournament structures instead of burning everything down and starting from scratch. The best that such a compromise can do is take football closer to what it was in the 1980s and ’90s — an imperfect landscape, but one where there is unpredictability and a modicum of fair competition.

Should such an arrangement fail to arrive, the cabal who plotted the Super League will be back. They, it is vital to remember, have only been delayed, not denied.

THE TIMELINE

April 18: The newly formed Super League releases a statement outlining its plan to “save football”. A total of 20 teams are supposed to comprise the League, with 12 founding members — Manchester United, Liverpool, Manchester City, Chelsea, Arsenal, Tottenham, Barcelona, Real Madrid, Atletico Madrid, Juventus, Internazionale, and AC Milan.

April 19: The Super League, with Florentino Pérez as its president, faces a barrage of criticism from former players and managers. The list of naysayers include former Man United captain Gary Neville and United’s legendary manager Sir Alex Ferguson.

April 20: Pep Guardiola, manager of Manchester City, argues why the Super League is “not sport”. With fans from several European clubs protesting in-person and millions more joining them on social media, Chelsea becomes the first team to back out of the new League, and within minutes, one founding member after another begins to drop out. The Super League releases another statement, this time declaring its cancellation.

THE REBELS

t2 profiles the men who dreamt of changing football, engineered the breakaway in form of the Super League, and failed:

Florentino Pérez

The president of Real Madrid has always seen himself as a pioneer. The Super League may have been Pérez’s most audacious attempt yet at overhauling the status quo, but it has been an attempt germinating for decades. Convinced that teams like Real Madrid should not waste their time playing against those who do not match their status and pedigree, Pérez is reported to be the catalyst behind the League — the man who believed federations, fans and governments would ultimately yield to his grand design for the future.

Andrea Agnelli

Italian business scion and chairman of Juventus, Italy’s most decorated football club, Agnelli has steadily harnessed a reputation of being a lonely man at the top. For the Super League, however, Agnelli worked closely with Pérez throughout, all the while convincing his associates at the European Club Association (ECA) that he fully backed reforms for the Champions League at the expense of the Super League. Over the last few days, Agnelli has been dubbed everything from a “visionary” to a “back-stabber” and a “snake”. His polarising image is unlikely to improve now that his brainchild has had a stillbirth.

Ed Woodward

Frequently cast as the corporate pantomime striving to undermine the spirit of football, Woodward had been the man in the shadows, pulling the strings for the formation of the Super League. Unlike Pérez or Agnelli, the Manchester United executive vice-chairman had rarely backed the idea of the League in public. This is why UEFA, the English FA, and fans in general were appalled by Woodward’s sudden volte-face to join the gang of rebels. Despite playing a critical role (as an investment banker) in securing funding from JP Morgan, the failure of the League means that Woodward stands red-faced, with his stock having never been lower.