From Doom to Call of Duty, first-person shooters have been popular for decades. But what if the thrill for video game fans was never really about the guns?

The just released Immortals of Aveum, for Windows computers and the latest PlayStation and Xbox consoles, tests this theory. The game, set in a fantasy world with several kingdoms at war over the control of magic, abandons the tried-and-true formula of arming players with guns and bazookas. Instead, they battle with bracelets. Or more precisely, sigils that cast spells.

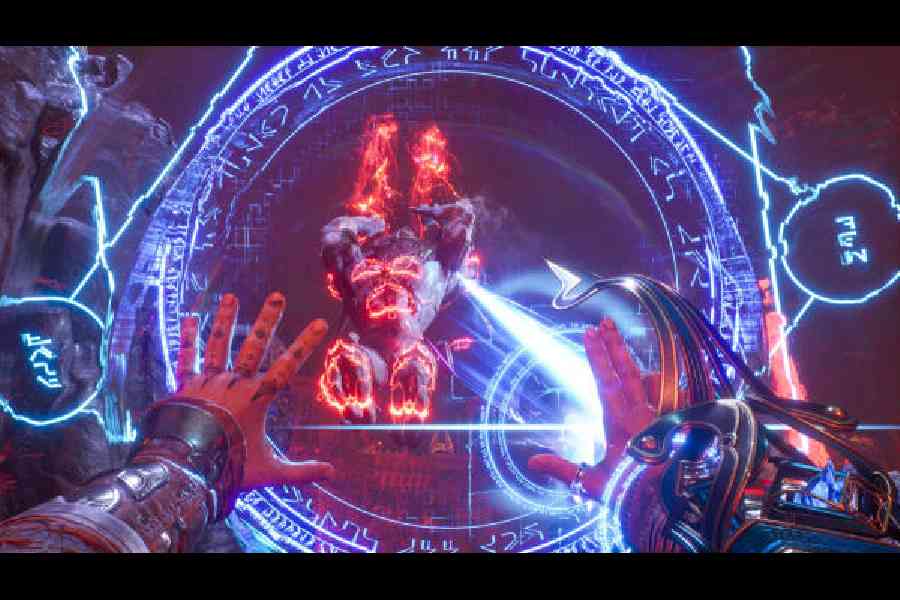

In the single-player game, a battlemage named Jak joins an elite militarylike force, collecting spells to make his sigils more potent. Players rotate among three coloured sigils that correspond to the familiar weapon classes in games such as Counter-Strike and Halo: the blue sigil shoots long-distance energy beams akin to a sniper rifle; the green sigil acts as a rapid-fire blaster; and the red sigil’s short-distance bursts are like a shotgun.

Immor-

tals of Ave-um is the first from Ascendant Studios, mostly composed of employees caught in a sizable layoff at Telltale Games that made The Walking Dead and Tales From the Borderlands. It is published by Electronic Arts as part of its indie label focusing on new intellectual property.

Ascendant’s founder, Bret Robbins, whose tenure includes Call of Duty, Lord of the Rings and James Bond titles, said that by swapping out guns for sigils, his team was taking a risk, as is always the case when creative professionals try to break ground. But the decision simply came down to making a game he wanted to play.

“I just didn’t see anyone making a fantasy version of a shooter — a big, epic, fast-paced, awesome fantasy game in the spirit of something like Call of Duty,” he said.

Guns have charmed gamers as far back as Duck Hunt, which was packaged with the Nintendo Entertainment System in 1985, but as a storytelling device, they tend to box video games into narratives that justify their presence. Early Call of Duty titles, known for their extensive weaponry inspired by real-life rifles, machine guns and pistols, centred on soldiers in WW II. Tom Clancy’s Rainbow Six has followed a counterterrorist organisation. Shooter games that took creative liberties often conformed to a similar mould — Doom, a progenitor of the genre, follows a Marine fighting monsters in outer space.

Replacing guns with magic could let Immortals of Aveum, which promises about 25 hours of gameplay, tell a more unconventional story. The protagonist, Jak, is an “unforeseen”, someone who preternaturally gains magic powers later in life; he fights alongside the Immortals, a group of battlemages.

Incorporating magical elements in first-person shooters is not a new phenomenon. BioShock featured “plasmids” that set objects ablaze, hypnotised enemies and fired lightning bolts. Each character in Destiny possesses distinct supernatural abilities.

Jose Zagal, who teaches courses on video game design at the University of Utah, US, said first-person shooters have evolved to add more complexity, challenge and speed to their gameplay. The basic concept of running around and firing a gun is not enough.

In this game, certain spell colours work better against particular types of enemies. Reflexes and timing will be tested with defence-shattering attacks, an energy shield and a magic whip to draw enemies in closer.

“It’s a different kind of design for an audience that’s more savvy and more demanding,” Zagal said.

When first-person shooters such as Wolfenstein 3D and Doom were arriving in the early 1990s, guns may have acted as a metaphor to make it simpler to grasp a new concept — that gamers could dash around a 3D environment and fire projectiles at enemies. But those weapons might not have been the true draw.

Similar to the mindfulness and satisfaction that people experience during activities that require intense focus, such as rock climbing, playing chess or composing a song, fans of first-person shooters may have been hooked by the complicated split-second decision-making — which, yes, involves shooting weapons at fast-moving objects.

Zagal said fresh game concepts usually just have to do well enough to raise funding for a sequel; the second game is where they peak. “I think what they’re doing is exciting,” he said.

NYTNS