The first images from the Webb Telescope have wowed the world with their beauty. But what do they mean for the future of astronomy? Planet Earth had its head in the sky when the James Webb Space Telescope's first images of the cosmos were revealed.

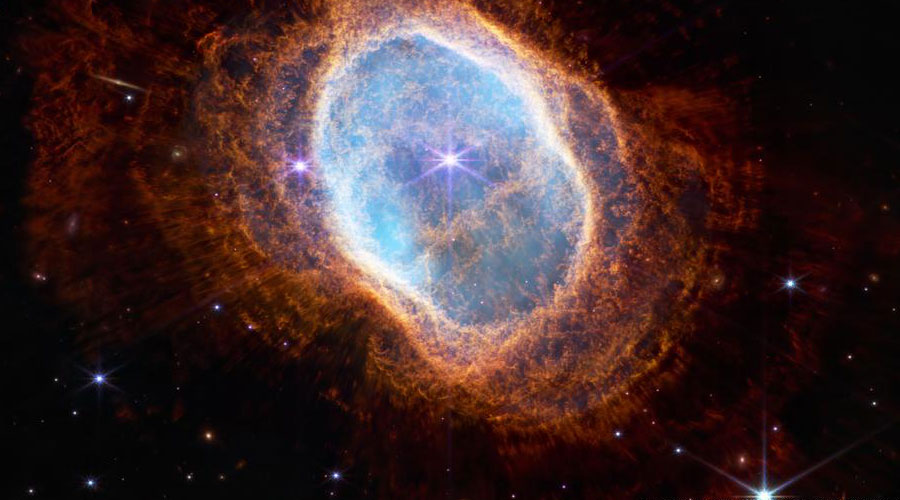

Five stunning images showcased the telescope's capabilities, capturing views of stars being born and a group of galaxies locked in a cosmic dance. The pictures are the deepest and sharpest color images of the universe so far.

While celebrating the beauty of the images, scientists have been keen to point out the scientific significance of the international project, which is a collaboration between NASA, the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Canadian Space Agency (CSA).

"These images show us that Webb works incredibly well. Webb will help us to study our universe in much more detail," said Kai Noeske, an astronomer and communications officer at the European Space Operations Centre (ESOC).

Looking back in timeWebb's first image was a deep field image of a tiny spec of the vast universe, showing distant galaxy clusters. Some of these galaxies are more than 13 billion years old and were created when the universe was in its infancy.

"It is light from the early universe, in its first 500 million years, which is reaching us today," Noeske told DW.

The curious effect of looking back in time is caused by the speed of light and how long light takes to reach us. Light travels at 300,000 kilometers every second (about 670 million miles per hour). This is extremely fast. But space is really big, so it can still take a long time for light to travel.

For example, the sun is about 150 million kilometers (93 million miles) from Earth, and it takes around eight minutes for light to reach us from our sun.

The objects in Webb's images are many billions of light-years away. One light-year is the distance traveled by light in one year, which is about 9.5 trillion kilometers.

This means the light has traveled through space and time to reach us over billions of years. We would have to wait another 13 billion years to see these galaxies as they are today.

The scale of these distances is difficult to imagine, but it certainly makes a walk to the store feel rather short by comparison.

Making the invisible visible

In the kaleidoscopic images of the Carina Nebula and Stephan's Quintet, Webb shows us emerging stellar nurseries where stars are being born and developing. Scientists have never been able to observe galaxies interacting in this much detail.

It's thanks to Webb's infrared cameras that we're able to see the stars in all their glory.

"Infrared gives us a lot more information on the young universe than was possible before. The light from these galaxies was stretched as it traveled to us. Webb lets us see that," says Noeske.

The colors in the Cosmic Cliffs were artificially added to the original image by Webb’s science team. However, that's not to say the colors are not there. In fact, the light emitted from stars contains information far richer than we can see with the human eye.

Researchers use data about light emitted from stars to understand how galaxies form, grow, and merge with each other, and in some cases why they stop forming stars altogether.

For example, blue galaxies contain stars but very little dust. The red objects are enshrouded in thick layers of dust, while green galaxies are populated with hydrocarbons and other chemical compounds.

"Webb will address some of the great, open questions of modern astrophysics: What determines the number of stars that form in a certain region? Why do stars form with a certain mass?" NASA said in a press release on Tuesday.

Richer information about the universe

It will take weeks and months to analyze the first images and demonstrate more of what Webb is capable of doing in the future.

Each photo we see is a composite of many hours of imaging. Study teams will "slice and dice" the information into many images for detailed study, much like clinicians do with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

"It was a big step forward from what Hubble showed us. The sharpness and level of detail made it clear how much potential Webb has for scientific research. Webb not only looks further back in time, but also in higher detail," Noeske told DW.

Webb will help scientists to answer questions about how planets, stars, galaxies, and ultimately the universe itself, are formed.

Finding Earth 2.0?

While less beautiful than the Cosmic Cliffs, Webb's spectrographic analysis of the exoplanet WASP-96 b's atmosphere is an example of perhaps more exciting information to come in the future.

WASP-96 b is a type of gas giant around 1,150 light-years away that bears little similarity to the planets in our solar system. Webb's team has analyzed the planet's transmission spectrum, measuring starlight filtered through the planet's atmosphere like a barcode.

"This is an amazing trick that astronomers use. The planet passes in front of its star — a bit of light passes through the planet's atmosphere, and that light shining contains the chemical signature of the atmosphere imprinted into it like a barcode," said Noeske.

The analysis showed the planet has an atmosphere that contains water, along with clouds and haze. But WASP-96b won't be supporting life as we know it any time soon, as the planet is made of gas and orbits its star extremely closely, making it an extremely hot and hostile environment.

The analysis of WASP-96 b provides a hint of what Webb has in store for exoplanet research. Exactly what will happen is yet to be determined.

The telescope is open to proposals from worldwide scientific communities about which exoplanets to study in the future.