One of the biggest myths of evolution is that it is a relentless march of progress. In fact, evolution is not a linear track, but a branching tree. New species do not arise as part of some long-term goal — they adapt to new opportunities in their surroundings.

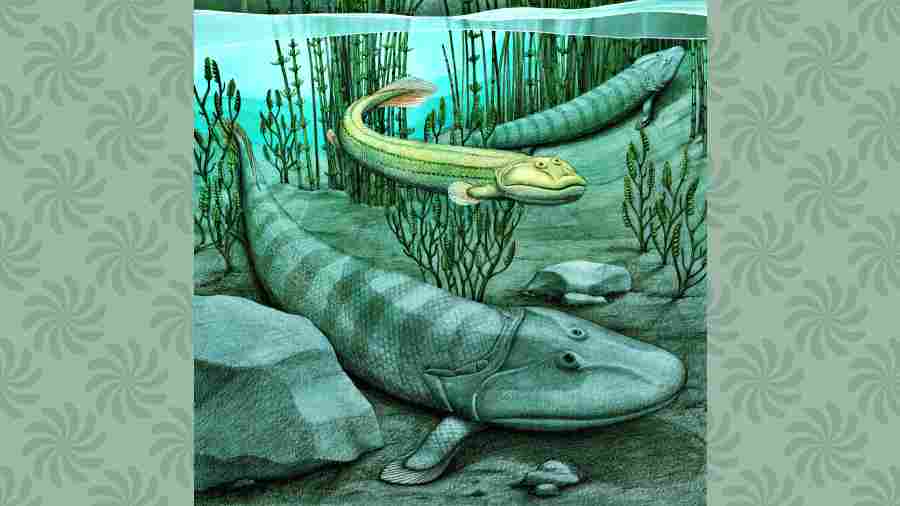

On July 20, palaeontologists unveiled a fossil that proved a potent antidote for the march-of-progress myth. It was a fish that lived about 375 million years ago, when our ancestors were scaly creatures vaguely resembling giant eels, walking across mud flats with four limbs complete with elbows, knees, wrists and ankles. The newly discovered fossil, called Qikiqtania wakei, belonged to this lineage.

But its anatomy suggests its ancestors, unlike ours, did not continue the move to land. Instead, they gave up walking to swim again.

“We think of evolution in directional terms,” said Neil Shubin, a palaeobiologist at the University of Chicago, US. “That’s not the case here. You have some species going to land and some actually returning to the water.”

In 2004, Shubin and his colleagues made a headline-grabbing discovery while searching for fossils in Nunavut, an Arctic territory of Canada. They discovered a large 375-million-year-old fish closely related to land vertebrates. Its most striking similarity was in its four leg-like fins.

The creature’s two front fins had bones corresponding to our humerus, radius, ulna and wrist bones. The combination allowed the fish, which they named Tiktaalik, to walk on mud flats and the bottom of swamps.

Tiktaalik’s importance came into sharp focus when scientists put it on an evolutionary tree along with land vertebrates — known as tetrapods — and other tetrapod-like fish. By looking at these branches, scientists could see how the tetrapod body evolved, step by step. Fish first evolved the long bones in their legs, later adding wrists and ankles. Later still, fingers and toes arose.

Now, Shubin and his colleagues have added yet another branch to our evolutionary tree with a fossil that they unknowingly discovered in Nunavut, even before finding Tiktaalik.

The team first went to Nunavut in 1998, attracted to rocks that looked as if they might contain fossils from the age of the earliest tetrapods. But one field season after another ended in disappointment.

When the researchers returned in 2004, they found something promising on a small hill next to their tents. “One day, I was having lunch at this spot, and I looked down, and I saw a field of white scales on dark rock,” Shubin said.

The scales had a distinctive diamond-like pattern only found on fish that are closely related to tetrapods. Near the dark rock, Shubin noticed a fish jaw fossil. And near that was a rock the size of a Frisbee, with bone-like specks on it.

Shubin socked away everything in a bag to take back to his laboratory, but four days later, the researchers discovered the first fossils of Tiktaalik at another site a mile away from camp.

In subsequent field seasons, the researchers found at least 10 specimens of Tiktaalik. They were able to chart the animal’s growth over its lifetime into a 9-foot-long beast.

The fossils allowed the scientists to reconstruct the walking style of Tiktaalik, a fish version of four-wheel-drive. They discovered that the animals hunted fish by biting down with their long fangs and sucking it down their throats.

In 2019, the researchers turned their attention back to the Frisbee rock. The University of Chicago, US, had purchased a CT scanner designed to produce high-resolution images of fossils, even when they are still in rocks.

After scanning the jaw and the scales, Thomas Stewart, a postdoctoral researcher in Shubin’s lab, finally got around to scanning the rock. To his astonishment, it contained a fairly complete fin.

The scientists dubbed the fossil Qikiqtania (pronounced kickkick-TAN-ee-ya) after the Inuktitut names for the region where it was found, Qikiqtaaluk and Qikiqtani. The second part of its name, wakei, honoured David Wake, an evolutionary biologist at the University of California, Berkeley, US, who was a mentor to Shubin and died last year.

A careful comparison of its anatomy confirmed that Qikiqtania was closely related to tetrapods and might be the closest known relative to Tiktaalik. But after Qikiqtania branched off from Tiktaalik, its evolution took a strikingly different path. For one thing, it got much smaller, likely measuring only about 30 inches long.

An even more dramatic change happened to Qikiqtania’s fins.

On Tiktaalik and other tetrapod-like fish, the humerus had knobs and ridges where powerful walking muscles were anchored. But Qikiqtania had a smooth humerus that offered little support for muscles.

The researchers found another striking difference in the elbow. Tiktaalik relied on its elbow to walk, bending its limb at a 90-degree angle into a pushup position. Qikiqtania’s elbow was locked, with its fin extended out in a straight line.

“It’s not a flexible limb — it’s like a paddle,” Shubin said.

Shubin suspected that Qikiqtania abandoned the walking habit that its ancestors had recently evolved, opting instead to swim in the open water something like a modern paddlefish.

To understand Qikiqtania’s striking evolutionary shift, Shubin pointed to tetrapods that returned to the water millions of years later. About 50 million years ago, for example, land mammals adapted into aquatic animals that would eventually become whales and dolphins. The discovery of Qikiqtania suggested that some of our ancient relatives gave up walking almost as soon as walking evolved.

But Qikiqtania did not return to the water simply by reverting to the bodies of its swimming ancestors. It probably used the new bite-and-suck attack that tetrapod-like fish evolved. “Not only are they returning to the water, but they’re doing it in new ways,” Shubin said.

NYTNS