In May 1889, people living in Bukhara, a city that was then part of the Russian Empire, began sickening and dying. The respiratory virus that killed them became known as the Russian flu. It swept the world, overwhelming hospitals and killing the old with special ferocity.

Schools and factories were forced to close because so many students and workers were sick. Some of the infected described an odd symptom: a loss of smell and taste. And some of those who recovered reported a lingering exhaustion.

The Russian flu finally ended a few years later, after at least three waves of infection.

Its patterns of infection and symptoms have led some virus experts and historians of medicine to now wonder: might the Russian flu actually have been a pandemic driven by a coronavirus? And could its course give us clues about how our pandemic will play out and wind down?

If a coronavirus caused the Russian flu, some believe that pathogen may still be around, its descendants circulating worldwide as one of the four coronaviruses that cause the common cold. If so, it would be different from flu pandemics whose viruses stick around for a while only to be replaced by new variants years later that cause a new pandemic.

If that is what happened to the Russian flu, it might bode well for the future. But there is another scenario. If today’s coronavirus behaves more like the flu, immunity against respiratory viruses is fleeting. That might mean a future of yearly Covid shots.

But some historians voice caution about the Russian flu hypothesis. “There is very little, almost no hard data” on the Russian flu pandemic, said Frank Snowden at Yale University, US.

There is, though, a way to solve the mystery of the Russian flu. Molecular biologists now have the tools to pull shards of old virus from preserved lung tissue from Russian flu victims and figure out what sort of virus it was.

Some researchers are now on the hunt for such preserved tissue in museums and medical schools that might have old jars of specimens floating in preservative fluid that still contain fragments of lung.

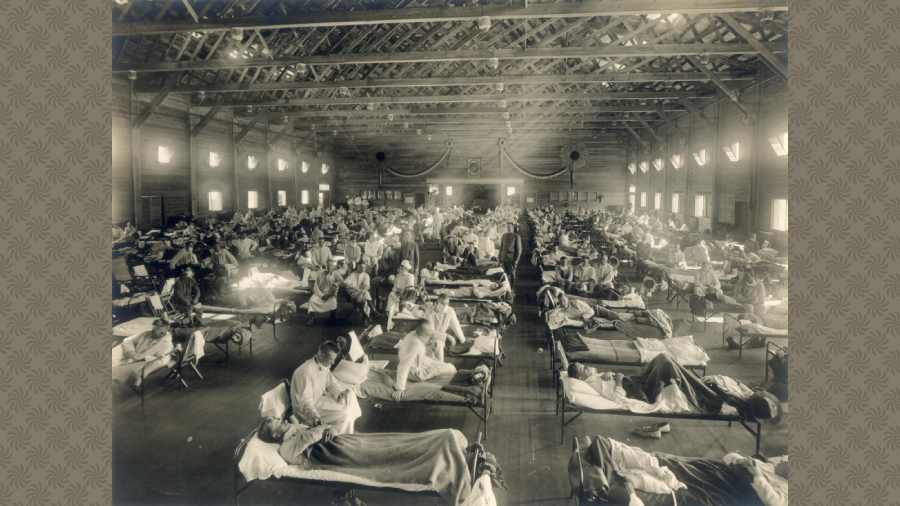

Tom Ewing of Virginia Tech, US, one of the few historians who has studied the Russian flu, can’t help noticing striking parallels with today’s coronavirus pandemic: institutions and workplaces shut down because too many people were ill, physicians overwhelmed with patients and waves of infection.

“I would say, maybe,” Ewing said when asked if the Russian flu was a coronavirus.

Dr Scott Podolsky, a professor of global health and social medicine at Harvard Medical School, US, called the idea “plausible”.

And Dr Arnold Monto, professor of public health, epidemiology and global health at the University of Michigan, US, considered it “a very interesting speculation”.

“We have long wondered where coronaviruses came from,” Monto said. “Has there ever been a coronavirus pandemic in the past?”

Harald Bruessow, a retired Swiss microbiologist and editor of the journal Microbial Biotechnology, points to a paper published in 2005 concluding that another coronavirus circulating today, known as OC43, which causes severe colds, may have jumped from cows to humans in 1890.

Three other less virulent coronaviruses circulate, too. Perhaps one of those viruses, or OC43, is a variant left over from the Russian flu pandemic.

Bruessow, while acknowledging the uncertainties, would bet that the Russian flu was caused by a coronavirus. His work, which involved delving into old newspaper and journal articles, and public health reports on the Russian flu, uncovered that some patients had complained about conditions like a loss of taste and smell and long Covid-like symptoms.

Some historians speculated that the 19th century’s fin de siècle might actually have been lassitude caused by sequelae of the Russian flu.

Such symptoms are not typical of flu pandemics.

Like Covid, Bruessow reports, the Russian flu seems to have preferentially killed older people but not children. Ewing, examining 1890 records from the State Board of Health in Connecticut, US, found a similar pattern. If true, that would make the 1890 virus unlike influenza viruses which kill the very young as well as the very old.

For those seeking hints to how the current coronavirus pandemic might end, some think those past two pandemics could offer a clue.

As the Russian flu pandemic waned, said J. Alexander Navarro, a historian at the University of Michigan, US, “people rather quickly went on with their lives.” It was the same with the 1918 flu pandemic. Newspaper stories about it dwindled. And, he said, “grieving was almost entirely a private affair.”

“I highly suspect that the same will occur today,” Navarro said. “In fact, in many ways, I think it already has.”

NYTNS