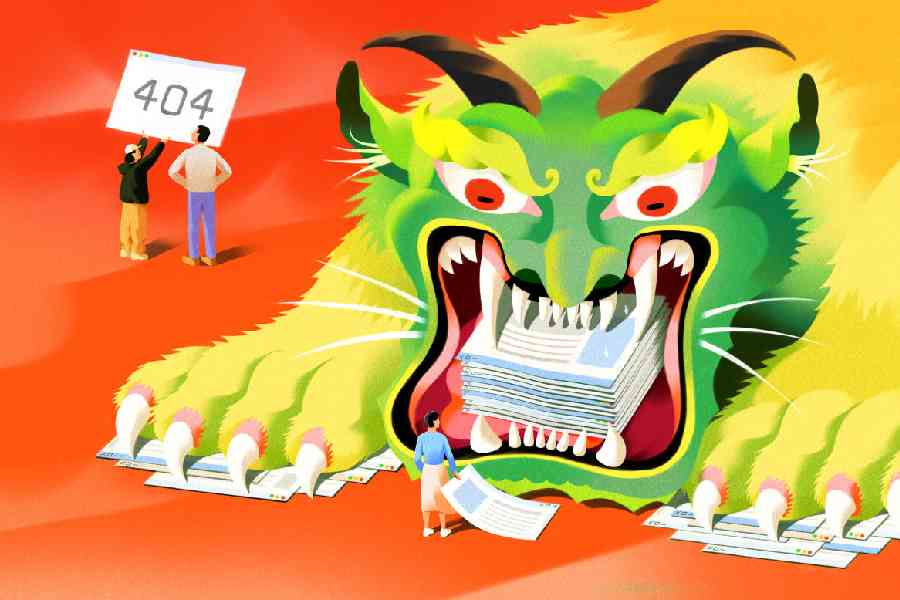

Chinese people know their country’s Internet is different. There is no Google, YouTube, Facebook or Twitter. They use euphemisms online to communicate the things they are not supposed to mention. When their posts and accounts are censored, they accept it with resignation.

Now they are discovering that, beneath a facade bustling with short videos, livestreaming and e-commerce, their Internet — and collective online memory — is disappearing in chunks.

A post on WeChat on May 22 that was widely shared reported that nearly all information posted on Chinese news portals, blogs, forums and social media sites between 1995 and 2005 was no longer available.

“The Chinese Internet is collapsing at an accelerating pace,” the headline said. Predictably, the post itself was soon censored.

“We used to believe that the Internet had a memory,” He Jiayan, a blogger who writes about successful businesspeople, wrote. “But we didn’t realise that this memory is like that of a goldfish.”

It’s impossible to determine exactly how much and what content has disappeared. But I did a test. I used China’s top search engine, Baidu, to look up some of the examples cited in He’s post, focusing on about the same time frame.

I started with Alibaba’s Jack Ma and Tencent’s Pony Ma, two of China’s most successful Internet entrepreneurs. I also searched for Liu Chuanzhi, the godfather of Chinese entrepreneurs, who made headlines when his company, Lenovo, acquired IBM’s personal computer business in 2005.

I looked, too, for results for China’s top leader, Xi Jinping, who during the period was the governor of two big provinces. Search results of senior Chinese leaders are always closely controlled. I got no results when I searched for Ma Yun, which is Jack Ma’s name in Chinese. I found three entries for Ma Huateng, which is Pony Ma’s name. A search for Liu Chuanzhi turned up seven entries.

There were zero results for Xi.

Then I searched for one of the most consequential tragedies in China in the past few decades: the Great Sichuan earthquake on May 12, 2008, which killed over 69,000 people. It happened during a brief period when Chinese journalists had more freedom than the Communist Party would usually allow, and they produced a lot of high-quality journalism.

When I narrowed the time frame to May 12, 2008, to May 12, 2009, Baidu came up with nine pages of search results, most of which consisted of articles on the websites of the central government or the state broadcaster Central Central Television.

There’s a broader problem: China’s Internet is shrinking. There were 3.9 million websites in 2023, down more than one-third from 5.3 million in 2017, according to the country’s Internet regulator.

One reason is it is technically difficult and costly for websites to archive older content. But in China, the other reason is political.

Many people have had their online existences erased.

Recently, Nanfu Wang found that an entry about her on a Wikipedia-like site was gone. Wang, a documentary filmmaker, searched her name on the film review site Douban and came up with nothing. Same with WeChat.

“Some of the films I directed had been deleted and banned on the Chinese Internet,” she said. “But this time, I feel that I, as a part of history, have been erased.”

Zhang Ping, better known as Chang Ping, was one of China’s most famous journalists in the 2000s. His articles were everywhere. Then in 2011, his writing provoked the wrath of the censors.

“My presence in public discourse has been stifled much more severely than I anticipated, and that represents a significant loss of my personal life,” he told me. “My life has been negated.”

“Even though we tend to think of the Internet as somewhat superficial,” said Ian Johnson, a longtime China correspondent and author, “without many of these sites and things, we lose parts of our collective memory.”

NYTNS