In the 1960s, Mabel Addis was an elementary school teacher in a small town in New York in the US when she was offered an opportunity that would make history: create an educational game with IBM.

What resulted was the Sumerian Game, an early video game that taught the basics of economic theory to sixth graders. In it, a student would act as the ruler of the Mesopotamian city-state of Lagash, in Sumer, in 3500 BC. The game was text-based, but it is believed to be the first to introduce storytelling and characters, and the first in a genre now known as edutainment. With her passion for history, Addis also brought a level of narrative to video games that had not been seen before. It also made Addis the first known female video game designer.

Born Mabel Lorene Holmes in May 21, 1912, in Mount Vernon, New York, to James Holmes and Mabel (Wood) Holmes, she dreamed of going to Greece and becoming an archaeologist. Her mother wasn’t keen on the idea: it was considered impractical for a woman to pursue such a career.

Instead, Addis boarded a train to New York City to study ancient history at Barnard College. Her career, which began with teaching eight grades in a one-room schoolhouse in 1935, spanned five decades, with a break to raise her daughter.

The opportunity to write a video game came about while she was teaching in Katonah, New York. At the time, there was a “crisis in small-school-district education,” said Alexander Smith, who wrote about the Sumerian game in his book They Create Worlds: The Story of the People and Companies That Shaped the Video Game Industry, Vol. 1: 1971-1982.

“Rural school districts,” he added in an interview, “were starting to find themselves overextended, in terms of trying to keep up with a modern curriculum.”

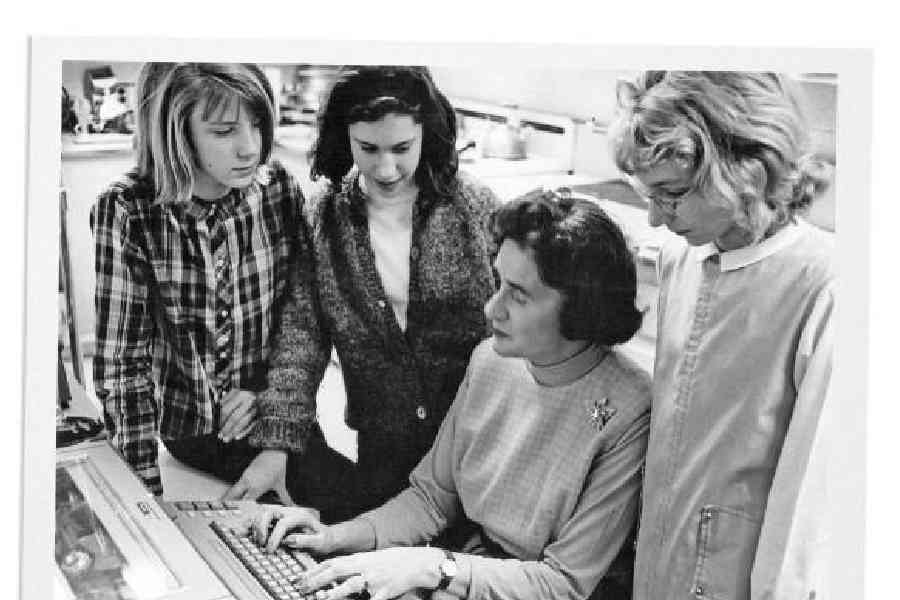

Bruse Moncreiff, who worked in IBM’s theoretical research unit, proposed creating an economic theory teaching game based in Sumer. Addis was intrigued by the idea and wrote the Sumerian Game, which was programmed by IBM employee William McKay.

The original game is thought to be lost, but documents from the era, including a report by Richard Wing, curriculum research coordinator for the board, and printouts from students’ gameplay, give a sense of the experience. A slide projector and a cassette player set the scene as students entered commands on a typewriter-like IBM 1050 linked to an IBM 7090 mainframe computer.

“If another teacher had written this game, they might’ve approached it like every other management game, where the computer simply acted as a calculator,” Willaert said. But Alexandra Johnson, Addis’ only child, remembered her mother as a playful educator who made history come alive. A 1966 article in Life described the students’ engagement with the game: “They love being king and become genuinely involved. When the machine relentlessly types out the deaths resulting from an insufficient ration of food, they have been known to pound the keyboards and cry aloud, ‘No! Don’t let it happen! Please don’t let it happen!’”

The Sumerian Game was a few years too early for its own good. The IBM computers were expensive to run, and funding for the programme soon ran out. The game proved influential, however, when it spawned offshoots.

In the late 1960s, a pared-down version, referred to as both King of Sumeria and the Sumer Game, was created by Doug Dyment, an employee of computer company Digital Equipment Corp. In 1973, author David Ahl adapted it for his book 101 BASIC Computer Games. This version, Hamurabi, was widely played among young computer hobbyists, some of whom went on to design their own games. (It also perpetuated a common misspelling of the Babylonian king’s name, Hammurabi.)

These versions kept the original game alive, Devin Monnens, a game historian who has traced the lineage of the Sumerian Game, said in an interview. “At any point along the way, this chain of events could have broken,” he said.

Addis died from complications of Alzheimer’s disease on August 13, 2004, in New York. She was 92.

In March 2023, the Game Developers Choice Awards honored Addis with a posthumous Pioneer Award, listing her innovations: “game updates, in-game narrative experiences, and early iterations of what would become known as cutscenes”.

NYTNS