Crying is a quintessential human experience. Other species produce tears, but the human species is the only one that scientists believe consistently cries not just to lubricate and protect the eyeballs, but also to express emotion.

While they are one of the few things that make us uniquely human, in many ways emotional tears remain an enigma. Still, some progress has been made to help us understand human tears — to grasp what they’re made of, why we create them (some of us more than others) and why producing them can help us feel better.

Practically any creature that has eyeballs produces two sets of tears: basal and reflex. Basal tears keep the eye moist, while reflex tears are meant to protect the eye from irritants like dust.

Humans also shed a third type, fittingly called emotional tears, when they are sad, frustrated, overwhelmed, happy or moved.

All three types of tears are structurally similar, in that they are primarily made of water, oils, mucus, antibacterial proteins and electrolytes, said Darlene Dartt, a professor of ophthalmology at Harvard Medical School in the US.

You rarely, if ever, notice basal tears, which are released in tiny amounts throughout the day. As they evaporate, the temperature on the surface of the eyeballs drops slightly, which signals that the eyes should produce more basal tears to avoid drying out.

Reflex and emotional tears release more liquid, which is why your eyes well up while you’re chopping onions or why tears stream down your face at a funeral. That extra liquid mainly comes from special tear glands located underneath the eyebrows that are regulated by cells in the brainstem. With reflex tears, nerves in the eyes signal to the brainstem that tears are needed to flush out whatever is irritating them. For emotional tears, scientists think that other parts of the brain activate those brainstem cells to turn on the tear glands.

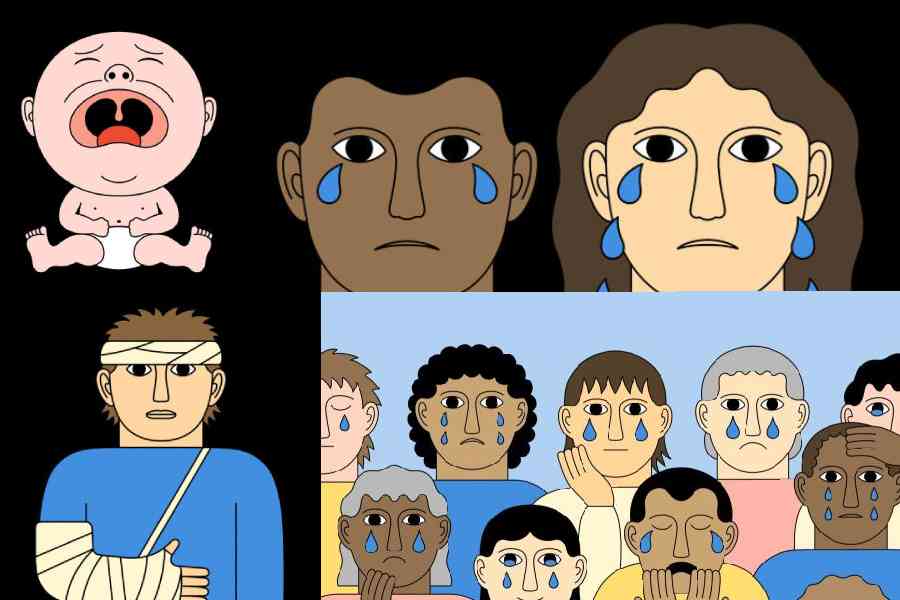

Lots of animals wail in distress. Experts think that they — and we — evolved to do so in infancy as a means of survival. That’s because the animals that cry vocally — namely, mammals and birds — tend to rely on a mother or father. A robin chick’s peeps and a goat kid’s bleats are the baby’s main way to solicit care from a parent when it’s hungry, scared or in pain.

But animals don’t shed emotional tears when they cry. And for the first several weeks of their lives, neither do humans. Instead, similar to other animals, newborn babies produce a heartbreaking (and ear-piercing) bawl. Then, sometime in the first month or two, salty fluid starts to fall from their eyes as well.

It’s a bit of a mystery why we started to produce tears while upset, rather than continuing to cry with dry eyes like sloths or bats do.

It’s possible that the act of scrunching up your face to unleash a yowl puts pressure on the eyeballs, stimulating the tear glands, said Ad Vingerhoets, an emeritus professor of clinical psychology at Tilburg University in the Netherlands and one of the foremost experts in human crying. That may be why yawning, laughing and vomiting can lead to tears as well, he added.

Tears may also hold an evolutionary advantage over howls, and as we age, we become more able to cry quietly. While anyone on an airplane can hear an infant wail, only those sitting in the seats near you will see tears roll down your cheeks while you watch the opening sequence of Up.

In that way, tears can more subtly alert others nearby to someone’s distress without giving the person away to predators that may be lurking, said Lauren Bylsma, an associate professor of psychiatry and psychology at the University of Pittsburgh in the US.

For the first years of our lives, we mostly shed tears related to our own experiences — a busted knee, a bee sting or a dropped ice cream cone.

That starts to change as we grow older and become more emotionally and socially developed. We cry less in response to physical pain and more over our emotional connections to other people. “Your world becomes greater, so there are more people who become more important for you,” Vingerhoets said.

One of the most common reasons for crying is the absence or loss of a loved one, whether we’re homesick as children, heartbroken in adolescence or grieving a death at any age. We cry over the plights of others, too. These empathetic tears may occur because we are imagining ourselves in other people’s shoes, whether they are friends, strangers or even fictional characters. In fact, this is how scientists study crying: they show people a sad clip from a film and see if it turns on the waterworks.

While sadness is the emotion most typically associated with crying, what many tearful experiences have in common is a sense of helplessness or powerlessness. That feeling of powerlessness often accompanies tears of frustration, and it may even explain the tears some people shed when they feel emotionally overwhelmed, whether from joy, anxiety or awe.

In fact, Vingerhoets called helplessness “the core element of crying”, since it harks back to the original evolutionary purpose of tears: needing assistance or support.

NYTNS