Sitting on a stool several feet from a long-armed robot, Dr Danyal Fer wrapped his fingers around two metal handles near his chest.

As he moved the handles — up and down, left and right — the robot mimicked each small motion with its own two arms. Then, when he pinched his thumb and forefinger together, one of the robot’s tiny claws did much the same. This is how surgeons like Dr Fer have long used robots when operating on patients. They can remove a prostate from a patient while sitting at a computer console across the room.

But after this brief demonstration, Dr Fer and his fellow researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, US, showed how they hope to advance the state of the art. Dr Fer let go of the handles, and a new kind of computer software took over. As he and the other researchers looked on, the robot started to move entirely on its own.

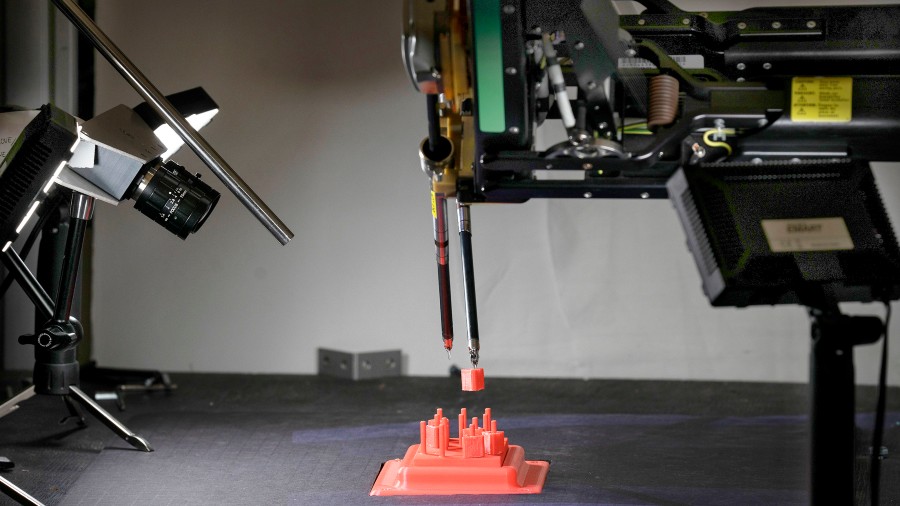

With one claw, the machine lifted a tiny plastic ring from an equally tiny peg on the table, passed the ring from one claw to the other, moved it across the table and gingerly hooked it onto a new peg. Then the robot did the same with several more rings, completing the task as quickly as it had when guided by Dr Fer.

The training exercise was originally designed for humans; moving the rings from peg to peg is how surgeons learn to operate robots like the one in Berkeley. Now, an automated robot performing the test can match or even exceed a human in dexterity, precision and speed, according to a research paper from the Berkeley team.

The project is part of a much wider effort to bring artificial intelligence into the operating room. Using the same technologies that underpin self-driving cars, autonomous drones and warehouse robots, researchers are working to automate surgical robots. These methods are still a long way from daily use, but progress is accelerating.

“It is an exciting time,” said Russell Taylor, a professor at Johns Hopkins University, US, and former IBM researcher well-known in the academic world as the father of robotic surgery. “It is where I hoped we would be 20 years ago.”

Five years ago, researchers with the Children’s National Health System in Washington DC, US, designed a robot that could automatically suture the intestines of a pig during surgery. While a notable step, it came with an asterisk: the researchers had implanted tiny markers in the pig’s intestines that emitted a near-infrared light and helped guide the robot’s movements.

The method is far from practical, as the markers are not easily implanted or removed. But in recent years, artificial intelligence researchers have significantly improved the power of computer vision, which could allow robots to perform surgical tasks on their own, without such markers.

The change is driven by what are called neural networks, mathematical systems that can learn skills by analysing vast amounts of data. By analysing thousands of cat photos, for instance, a neural network can learn to recognise a cat. In much the same way, a neural network can learn from images captured by surgical robots.

Surgical robots are equipped with cameras that record three-dimensional video of each operation. The video streams into a viewfinder that surgeons peer into while guiding the operation, watching from the robot’s point of view.

But afterward, these images also provide a detailed road map showing how surgeries are performed. They can help new surgeons understand how to use these robots, and they can help train robots to handle tasks on their own. By analysing images that show how a surgeon guides the robot, a neural network can learn the same skills.

This is how the Berkeley researchers have been working to automate their robot. They collect images of the robot moving the plastic rings while under human control. Then their system learns from these images, pinpointing the best ways of grabbing the rings, passing them between claws and moving them to new pegs.

But this process came with its own asterisk. When the system told the robot where to move, the robot often missed the spot by millimeters. Over months and years of use, the many metal cables inside the robot’s twin arms have stretched and bent in small ways, so its movements were not as precise as they needed to be. Human operators could compensate for this shift, unconsciously. But the automated system could not.

The Berkeley team decided to build a new neural network that analysed the robot’s mistakes and learned how much precision it was losing with each passing day. “It learns how the robot’s joints evolve over time,” said Brijen Thananjeyan, a doctoral student on the team. Once the automated system could account for this change, the robot could grab and move the plastics rings, matching the performance of human operators.

Other labs are trying different approaches. Axel Krieger, a Johns Hopkins researcher who was part of the pig-suturing project in 2016, is working to automate a new kind of robotic arm, one with fewer moving parts and that behaves more consistently than the kind of robot used by the Berkeley team. Researchers at the Worcester Polytechnic Institute, US, are developing ways for machines to carefully guide surgeons’ hands as they perform particular tasks, like inserting a needle for a cancer biopsy or burning into the brain to remove a tumour.

“It is like a car where the lane-following is autonomous but you still control the gas and the brake,” said Greg Fischer, one of the Worcester researchers.

NYTNS