In a laboratory in downtown Medellín, Colombia, it is lunchtime: a technician in a white coat carries a loaded tray into a steamy nursery. She walks between rows of white mesh cages, each the size of a minifridge, and slides a thin tray of blood into every one. In response, her charges, all 1,00,000 of them, begin to whir and emit an excited hum.

This is a mosquito factory. Each week, it churns out more than 30 million adult Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. The brood stock of femalesis fed on discarded blood bank donations, and horse blood. Eventually, some of their progeny will be released into Medellín, Cali, and cities and towns in Colombia’s verdant river valleys. Other insects will be chilled into a stupor for a journey up to Honduras.

The elaborate effort is part of an experiment.

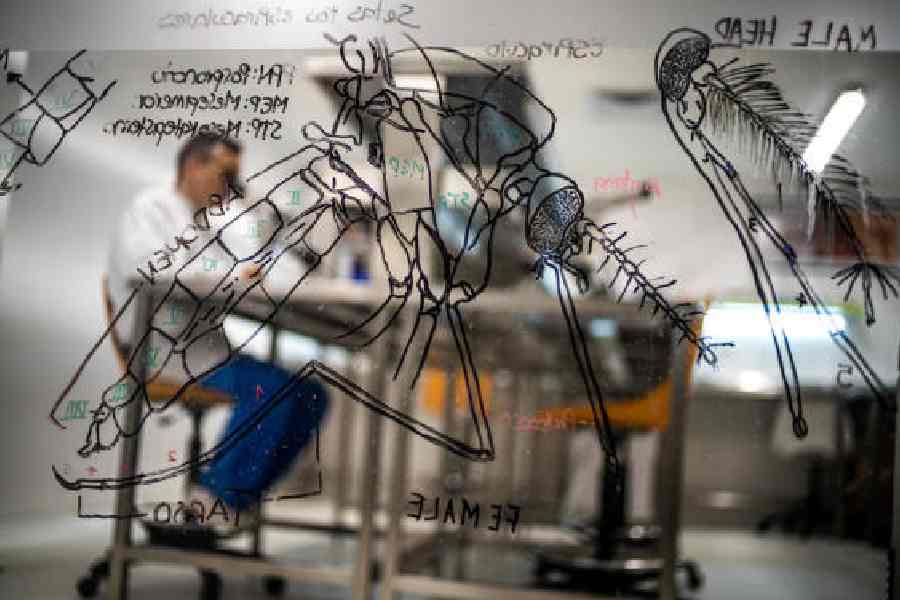

Aedes aegypti spreads arboviruses, including dengue and yellow fever, which can severely sicken or kill people. But these are special Aedes aegyptis: they carry a type of bacteria that can neutralise those deadly viruses.

Five decades ago, entomologists confronting the many kinds of suffering that mosquitoes inflict on humans began to consider a new idea: what if, instead of killing the mosquitoes (a losing proposition in most places), you could disarm them? Even if you couldn’t keep them from biting people, what if you could block them from passing on disease? What if, in fact, you could use one infectious microbe to stop another?

These scientists began to consider a parasitic bacteria called Wolbachia, which lives quietly in all kinds of insect species. A female mosquito with Wolbachia passes it on in her eggs toall of her offspring, who eventually pass it on to the next generation.

But Wolbachia isn’t naturally found in the mosquito species that cause humans the most problems — the Aedes aegypti, the virus carrier, and the Anopheles subspecies, which carry malaria. If it were, it might eventually render those species essentially harmless.

So, how do you infect a mosquito with Wolbachia?

Researchers found, after painstaking trial and error, that they could insert the bacteria into mosquito eggs using minute needles. The mosquitoes that grew from those eggs were infected.

The Aedes aegypti mosquitoes that hatched and lived with Wolbachia did just fine. And as hoped, the Wolbachia mostly blocked the viruses: the mosquito that bit someone with dengue, and picked up the virus, didn’t pass it on to the next person it bit.

That got the researchers thinking: if they could infect all the mosquitoes in a village or city, they might stop the disease. This method would not harm the ecosystem either.

But how do you get Wolbachia into all the mosquitoes in a city the sizeof Medellín?

Once they were confident they could infect generations of mosquitoes in the lab, the scientists needed to know if their theory would work in the wild. The method was first tested in small towns in northern Australia, where females with Wolbachia released in the field mated with wild males and did, indeed, spread Wolbachia through the mosquito population.

A team led by an Australian entomologist, Scott O’Neill, next tried some towns in Vietnam, and then a small city in Indonesia. There, after three years, areas where Wolbachia had been released had 77 per cent fewer cases of dengue reported and 86 per cent fewer hospitalisations.

Those results were stunning — a delight for a population used to miserable dengue seasons, and a huge relief for the public health system. Dengue causes intense suffering in even “mild” cases — it’s commonly called “breakbone fever” — and 5 per cent of cases progress to the haemorrhagic form of the disease, with uncontrolled bleeding. Half of the people who develop haemorrhagic dengue die if they do not have access to treatment to control the bleeding. There are no antiviral drugs to kill the dengue virus, and the search for a safe and effective vaccine has been long and fraught.

Mosquitoes are increasingly resistant to insecticides. But the Wolbachia trial results in Indonesia suggested that if the Wolbachia-carrying mosquitoes supplanted the local population, then the bacteria might be established for good and no further mosquito control would be needed.

From Indonesia, O’Neill’s group took their testing to Brazil. Another group, called WolBloc and run by University of Glasgow entomologist Steven Sinkins and his colleagues, began a trial in a neighborhood of Kuala Lumpur, the capital city of Malaysia, using a different strainof Wolbachia.

And Medellín, with a population of 3 million, is the biggest test to date.

There is the matter of the evolutionary battle underway inside every infected mosquito: the arboviruses need to spread to survive, so they’re trying to find a way to overcome the ability of Wolbachia to disarm them. Quite likely, they eventually will, O’Neill said, but he predicts it won’t be soon.

“It might happen on an evolutionary timescale, maybe decades, maybe more like 10,000 years,” he said. “But I’d be content with a few decades, to allow other technologies to develop.”

If the arboviruses move into other mosquito species, that’s a separate problem. But Wolbachia could move into other species, too: the WolBloc team has had some early success in preventing malaria transmission by mosquitoes infected with Wolbachia. That holds enormous promise for countries such as those in West Africa that have heavy burdens of arboviruses and malaria.

In Medellín, mosquitoes have shifted from menace to irritant. “You don’t hear people talk much about dengue these days,” Victoria said. “If people can just forget about it — that would be a tremendous thing.”

NYTNS