Inspired by how snakes move, engineers have created a robot that can stably climb large steps, an advance that may lead to better search and rescue robots that can successfully navigate treacherous terrain.

The robot, described in the journal Royal Society Open Science, climbed steps as high as 38 per cent of its body length with a nearly perfect success rate.

“We look to these creepy creatures for movement inspiration because they're already so adept at stably scaling obstacles in their day-to-day lives. Hopefully our robot can learn how to bob and weave across surfaces just like snakes,” said study co-author Chen Li from The Johns Hopkins University.

Li said earlier studies had observed snake movements on flat surfaces, but rarely in 3D terrain except for on trees.

According to him, until now engineers attempting to mimic snake movements have not accounted for real-life large obstacles such as rubble and debris that search and rescue robots would have to climb over.

Li and his team studied how the variable kingsnake -- commonly found living in both deserts and pine-oak forests -- climbed steps in the lab.

“These snakes have to regularly travel across boulders and fallen trees; they're the masters of movement and there's much we can learn from them,” Li said.

The scientists ran a series of experiments, changing step height and the steps' surface friction to observe just how the snakes contorted their bodies in response to these barriers.

They found that the snakes partitioned their bodies into three sections.

The front and rear body of snakes wriggled back and forth on the horizontal steps like a wave while their middle body section remained stiff, hovering just so, to bridge the large step, the researchers explained.

The wriggling portions, they said, provided stability to keep the snake from tipping over.

As the snakes got closer and onto the step, the researchers found that the three body sections travelled down each body segment.

As more and more of the snake reached the step, its front body section got longer and its rear section got shorter while the middle body section remained roughly the same length, suspended vertically above the two steps, the study noted.

When the steps got taller and more slippery, the scientists said the snakes would move more slowly and wriggle their front and rear body less to maintain stability.

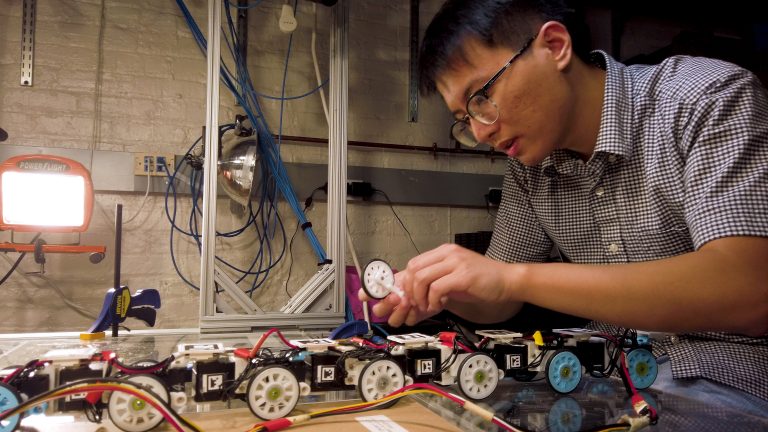

Analyzing the videos, and noting how snakes climbed steps in the lab, the researchers created a robot to mimic the reptile's movements.

They said the robot snake, at first, had difficulty staying stable on large steps and often wobbled and flipped over or got stuck on the steps.

The scientists then inserted a suspension system into each body segment so it could compress against the surface when needed.

After making the adjustments, they said, the snake robot was less wobbly, more stable and climbed steps as high as 38 per cent of its body length with a nearly 100 per cent success rate.

However, the study noted that a downside of the added body suspension system was that the robot used more electricity.

“The animal is still far more superior, but these results are promising for the field of robots that can travel across large obstacles,” Li said.