For the last two weeks, I’ve added an extra step to my bedtime routine: strapping a computer around my wrist.

Sleep tracking is still a nascent area that tech companies are experimenting with — one that I’ve watched with interest as someone who has been sleep deprived for many years. In the past, I’ve tried several gadgets with sleep tech but I hadn’t tracked my sleep habits and patterns. Would it make a difference, I wondered, to have this data? Would it help me sleep better?

I decided to test it out. I wore an Apple Watch and downloaded a top-rated app called AutoSleep that uses the watch’s sensors to follow my movements and determine when I fell asleep and woke up. (The watch lacks a built-in sleep tracker.)

But the excitement ended there. Ultimately, the technology did not help me sleep more. It didn’t reveal anything that I didn’t already know, which is that I average about five and a half hours of slumber a night. And the data did not help me answer what I should do about my particular sleep problems. In fact, I’ve felt grumpier since I started these tests.

That mirrored the conclusions of a recent study from Rush University Medical College and Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine in the US. The researchers warned that sleep-tracking tech could provide inaccurate data and worsen insomnia by making people obsessed with achieving perfect slumber, a condition they called orthosomnia. It was one of the latest pieces of research supporting the idea that health apps don’t necessarily make people healthier.

For practical tips on how to get more shut-eye, I sought out Raphael Vallat, a postdoctoral researcher at the Center for Human Sleep Science at the University of California, Berkeley, US. His most important advice: Do not check your sleep data on a regular basis. “If you look at your data, it can modify the perception of your sleep,” he said. “You may think, Oh gosh, I didn’t sleep well. Should I be tired? Am I in a bad mood?”

Here’s what I learned after two weeks of sleep tracking.

Sleep cycles

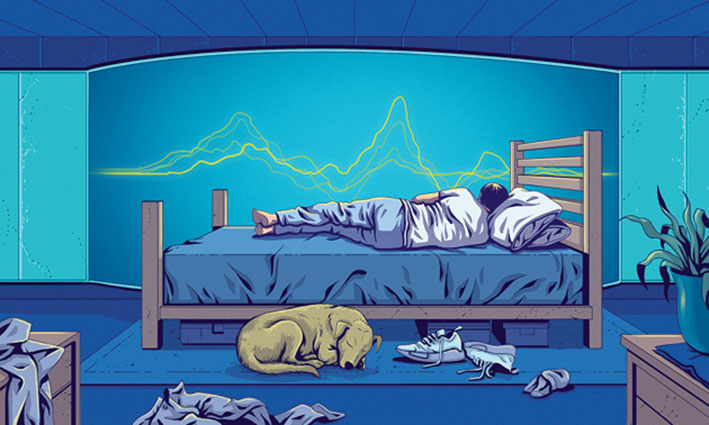

To understand sleep-tracking data, I delved into how sleep works. There are three main stages: light sleep, deep sleep and REM sleep (for rapid eye movement). The deep sleep stage is beneficial for physical restoration, such as muscle reparation and metabolism recovery. REM sleep, in which we dream, helps repair our psychological and emotional networks.

On average, a person completes a sleep cycle, which includes each of the three main stages, every 90 minutes. To get a good night’s sleep, you need to complete four to five cycles. That’s partly because the cycles are not the same throughout the night: The early cycles have more deep sleep, whereas the later ones have more REM sleep.

But our sleep-tracking tech? It generally can’t accurately measure REM sleep.

In sleep-tracking labs, the equipment typically includes sensors that are connected to someone’s face and neck to measure eye and brain activity, among other variables. But sleep-tracking apps for wearable devices such as the Apple Watch or Fitbit primarily look at movement and heart rate to determine when you are asleep or awake — which are generally not precise enough to measure the different sleep stages. Without a good look at REM sleep, those apps give an incomplete picture of sleep quality.

What to do?

My sleep-tracking statistics said I needed more sleep. (Duh.) Buried deep inside the data was some general information about sleep, but the app stopped short of offering advice on how to solve my personal sleep problems.

Dr Ethan Weiss, a cardiologist at the University of California, San Francisco, US, has been wearing a ring on his finger called Oura Ring, which includes a sleep tracker, for nearly a year. He said that while the device most likely had a rough sense of when he was sleeping and awake, he didn’t know whether the information about sleep stages was accurate — let alone what to do with it. “The question is can you do anything to optimise it? Or is the information worthless or making things worse? Sometimes being aware of it just makes you even more anxious,” he said.

Vallat told me that if I wanted better sleep, I should try to sleep and wake up at the same time every day — that would help my brain learn to build a structure for optimal sleep. He also advised making the bedroom a cool environment (about 20° Celsius) and as dark as possible; avoiding alcohol in the evening; not checking email or social media before bed; and asking myself each morning when I woke up: “Do I feel refreshed?”

That all sounded reasonable — and there’s no app needed for any of that.