This October, the Biden administration announced its intention to withdraw the nation’s most powerful weapon from the US nuclear arsenal.

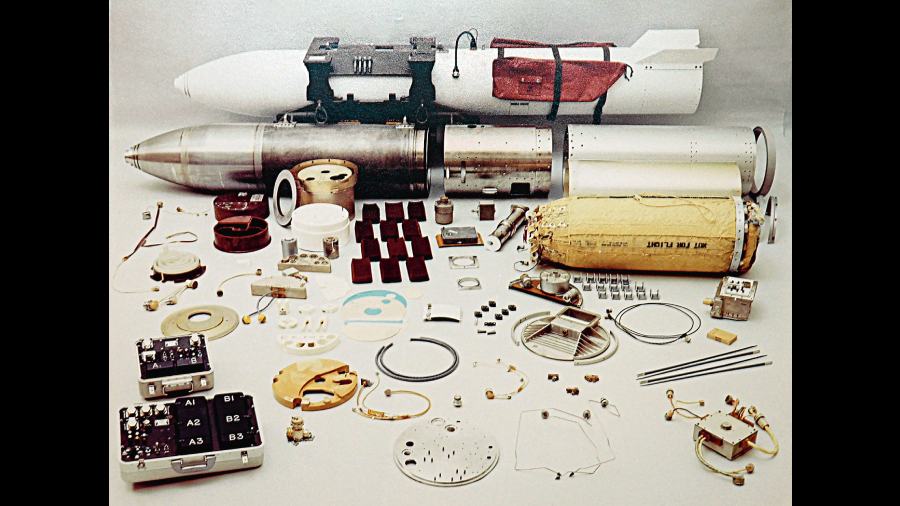

The bomb is called the B83. It is a hydrogen bomb that debuted in 1983 — a time when President Ronald Reagan was denouncing Russia as “an evil empire”. The government made 660 of the deadly weapons, which were to be delivered by fast bombers. The B83 was 12 feet long, had fins and packed an explosive force roughly 80 times greater than that of the Hiroshima bomb. Its job was to obliterate hardened military sites and command bunkers, including Moscow’s.

What now for the B83? How many still exist is a federal secret, but not the weapon’s likely fate, which may surprise anyone who assumes that getting rid of a nuclear weapon means that it vanishes from the face of the earth.

Typically, nuclear arms retired from the US arsenal are not melted down, pulverised, crushed, buried or otherwise destroyed. Instead, they are painstakingly disassembled, and their parts, including their deadly plutonium cores, are kept in a maze of bunkers and warehouses across the United States. Any individual facility within this gargantuan complex can act as a kind of used-parts superstore from which new weapons can — and do — emerge.

“It’s like a giant Safeway,” said Hans M. Kristensen, director of the Nuclear Information Project at the Federation of American Scientists, a private research group in Washington, US. “You go in with a bar code and get what you need.”

One weapon that nuclear planners want to make from recycled parts and designs is the W93 — billed as the first new warhead for the nation’s nuclear arsenal since the Cold War. The Biden administration announced the weapon’s birth in March and estimated it would cost up to $15.5 billion. The finished warhead would sit atop submarine missiles starting in or around 2034. Despite its description as new, the official government plan states that the weapon will be “anchored on previously tested nuclear components,” not new explosive parts.

“It’s bizarre how these things cycle around,” Kristensen said. “It’s nuclear whack-a-mole. You hit one down, and another pops up.”

The recycling has no direct bearing on the overall size of the nation’s nuclear arsenal, as the reused explosive parts are often employed for making replacement weapons, not new ones. That’s the case with the W93s, which are to replace or supplement old submarine warheads.

Even so, such recycling makes advocates for greater arms control livid. “Getting rid of them would be a good thing,” said Frank N. von Hippel, a nuclear physicist who advised the Clinton White House and now teaches at Princeton University, US. “It would signal that we have no expectation of rebuilding our arsenal.”

But hawks see the stored parts as crucial for the hedging of nuclear bets.

“It’s important to keep these parts around,” said Franklin C. Miller, a nuclear expert who held federal posts for three decades before leaving government service in 2005. “If we had the manufacturing complex we once did, we wouldn’t have to rely on the old parts.” He added that other nuclear powers can and do make new atomic parts.

Beyond the weapon debate, critics of atomic recycling warn that the nuclear storage complex is a disaster waiting to happen. It has a long history of accidents, safety lapses and security failures that could lead to a nuclear catastrophe.

“It’s dangerous,” said Robert Alvarez, a nuclear expert who, from 1993 to 1999 during the Clinton administration, was a policy adviser to the US Department of Energy, which runs the nation’s atomic infrastructure. “And it’s getting more dangerous, as the quantities in storage have increased.”

The plutonium cores of retired hydrogen bombs are of particular concern, Alvarez and others say. Roughly the size of a grapefruit, these cores are usually referred to as pits. The United States now has at least 20,000 pits in storage. They’re kept at a sprawling plant in the Texas panhandle known as Pantex. Plutonium is deadly to humans in tiny amounts, and that greatly complicates its safekeeping.

If recycled, pits from the B83 bombs would enter plutonium bunkers at Pantex that are already overcrowded and overtaxed. Alvarez said torrential rains in 2010 and 2017 flooded a major plutonium storage area at the Pantex site. Repairs, he added, cost hundreds of millions of dollars.

The Pentagon has given the old weapon no public support. Officials say an overhaul meant to extend the weapon’s life would be costly and in any case would put bombers in jeopardy because they would have to fly so close to targets.

Newer arms use satellite guidance, so bombers can drop their weapons from afar. For instance, the B61 model 12 has a computer brain and four manoeuvrable fins that let it zero in on deeply buried targets. To be deployed in Europe late this year, it is a designated replacement for the B83. And yes, its explosive parts come from the atomic recycling bin.

NYTNS