A big tech company with billions of users introduces a new social network. Leveraging the popularity and scale of its existing products, the company intends to make the new social platform a success. In doing so, it also plans to squash a leading competitor’s app.

The year was 2011 and Google had just rolled out a social network called Google+, which was aimed as its “Facebook killer”. Google thrust the new site in front of many of its users who relied on its search and other products, expanding Google+ to more than 90 million users within the first year.

But by 2018, Google+ was rele- gated to the ash heap of history. Despite the giant’s enormous audience, its social network failed to catch on as people continued flocking to Facebook — and later to Instagram and other social apps.

In the history of Silicon Valley, big tech companies have often become even bigger tech companies by using their scale as a built-in advantage. But bigness alone is no guarantee of winning the fickle and faddish social media market.

This is the challenge Mark Zuckerberg now faces as he tries to dislodge Twitter and make Threads the prime app for real-time, public conversations.

“If you launch a gimmick app or something that isn’t fully featured quite yet, it might be counter productive and you could see a lot of people churn right back out the door,” said Eric Seufert, an independent mobile analyst.

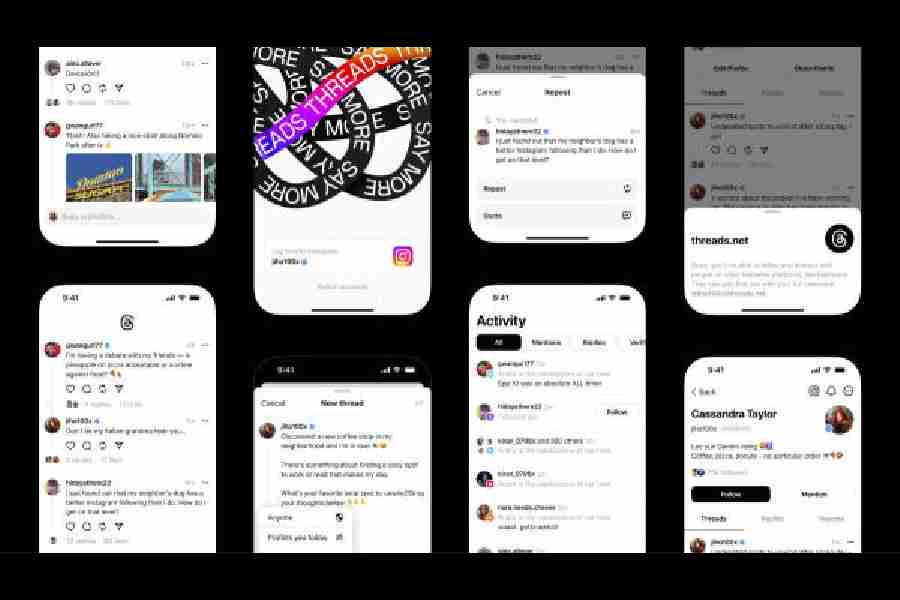

Within hours of the app’s introduction July 5, Zuckerberg said 10 million people had signed up for Threads. By Monday, that had soared to 100 million people.

Seufert called the numbers that Threads racked up “objectively impressive and unprecedented.”

Elon Musk, who owns Twitter, has appeared agitated by Threads’ momentum. With 100 million people, Threads is quickly surging toward some of Twitter’s last public user numbers.

On the same day that Threads was unveiled, Twitter threatened to sue Meta over the new app. Musk called Zuckerberg a “cuck” on Twitter. Then he challenged Zuckerberg to a contest to measure a specific body part and compare whose was larger, alongside an emoji of a ruler. Zuckerberg has not responded.

What Musk lacks at Twitter, Zuckerberg has in abundance at Meta: enormous audiences. Over 3 billion users visit Zuckerberg’s constellation of apps, including Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp and Messenger.

Zuckerberg has had plenty of experience nudging millions of people in those apps to use another of the apps. In 2014, for instance, he removed Facebook’s private messaging service from inside the social network’s app and forced people to download another app, called Messenger, to continue using the service.

Threads is now tied closely to Instagram. Users are required to have an Instagram account to sign up. People can import their entire following list from Instagram to Threads with just one tap of the screen, saving them from trying to find new people to follow.

Some wonder why Threads seems to have made its debut without some basic functions that are used inside Instagram.

“There are a lot of features Threads did not launch with, possibly by design, to keep it brand safe” and minimise controversy from the start, said Anil Dash, a tech industry veteran and writer.

Adam Mosseri, the head of Instagram, said in a Threads post that there was a running list of new features to add that people have requested. “They say, ‘make it work, make it great, make it grow,’” he wrote, adding, “I promise we will make this thing great.”

Yet bolting on a new app to a company’s existing products can eventually run out of steam.

In 2011, after Larry Page, Google’s co-founder and then CEO, cloned Facebook with Google+, users soon grew bored of the novelty of the new social network and stopped using it. Some saw Google+ as something that was forced on them while they were just trying to gain access to their Gmail.

In a postmortem of what went wrong, one ex-Googler wrote that Google+ mainly defined itself by “what it wasn’t — i.e. Facebook.