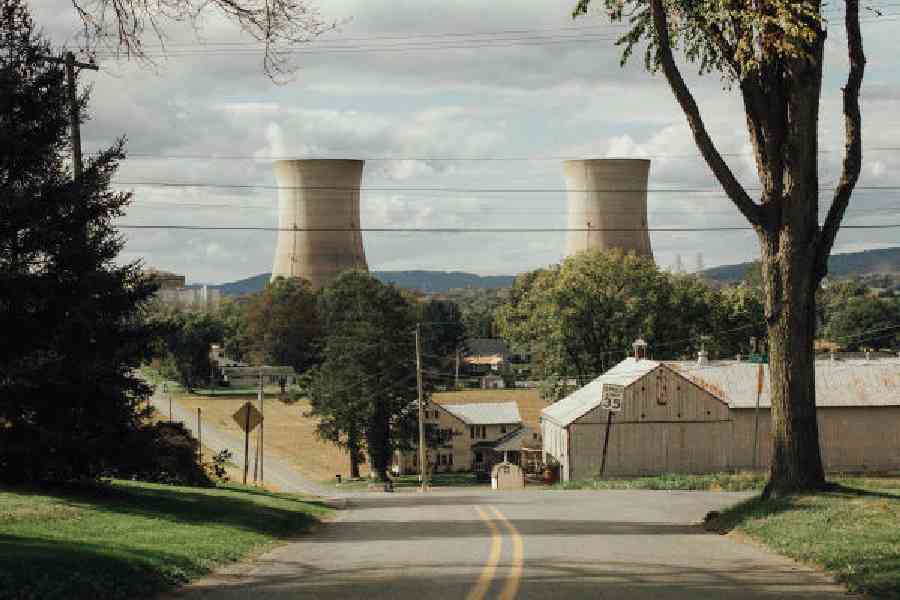

The concrete cooling towers that rise from a sliver of land south of Pennsylvania’s capital became symbols nearly a half-century ago of the risks of nuclear energy.

Now, a plan to restart one of the two reactors on Three Mile Island in the US is at the leading edge of efforts to greatly expand the country’s reliance on atomic fission to meet the growing power demands of homes, businesses and data centres.

Refurbishing this ageing plant — a fenced-off maze of pipes, valves, pumps and turbines in the middle of the Susquehanna River — depends on the financial backing of Microsoft. The technology giant has agreed to buy all of the electricity the plant generates, most likely starting in 2028, for 20 years.

Three Mile Island’s proposed revival reflects how vastly the perspectives on nuclear power in the US have shifted since a cooling failure led to the partial meltdown of one of the island’s reactors in 1979.

Once the target of fierce opposition, nuclear power plants are now coveted for generating large amounts of electricity round the clock without releasing the emissions that contribute to climate change. What’s less clear is whether expanding US nuclear capacity will pencil out economically.

Joseph Dominguez, the CEO of Constellation Energy, which bought the reactor in 1999, is confident that he is laying the groundwork not just to bring Three Mile Island back to life but also to add further to the company’s nuclear power fleet, the largest in the country.

“Twelve months from now, Constellation will have started on the path towards building new reactors,” Dominguez said recently.

No reactor set to close permanently has been brought back online in the US, and only three new ones have been completed in the past quarter-century.

If Constellation and others succeed in scaling up nuclear power — currently around 19 per cent of the US electricity mix — the result would largely be due to the financial backing of some of the world’s most valuable companies. These plants would also be eligible for federal tax credits.

Microsoft is effectively paying Constellation to bring Three Mile Island back online, while Google and Amazon recently struck deals with start-ups developing smaller reactors that they hope will power up in the 2030s.

All three tech giants have pledged to decarbonise their operations, but their data centres are consuming huge amounts of energy, making those goals much more difficult to meet.

If this proves to be another false start for the nuclear industry, it will mean all the money in the world wasn’t enough to overcome the technological and regulatory hurdles to expanding the use of fission, in which atoms are split to create heat and make steam that is used to generate electricity.

“It’s an industry with a really substantial burden of proof based on all of the disappointments — all of the very expensive disappointments,” said Peter A. Bradford, who served on the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission during the partial meltdown at Three Mile Island in March 1979.

It was then that America began to fall out of love with nuclear power.

Studies ultimately found that the radiation caused by the meltdown had a “negligible” effect on people’s physical health and the environment, according to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

Public backlash was swift, however — and grew after the 1986 accident at the Chernobyl nuclear plant in Ukraine. Facing steep construction costs and heightened public opposition, dozens of planned reactor projects were cancelled.

Three Mile Island’s undamaged reactor, down for refuelling during the accident, remained offline for the next six years. It resumed operations in 1985 over the objections of residents and activists, providing power for nearly 34 years before shutting down in 2019 as utilities opted for cheaper electricity from natural gas plants.

By early 2023, Constellation was exploring whether to fuel it up again as long-flat US electricity demand was poised to rise.

In addition, the dangers posed by climate change have become more visible in the wildfires scorching the West and the hurricanes buffeting the Southeast.

Nuclear power had also grown more popular. “The trade-off is: are you concerned about the dangers of nuclear power, or are you more concerned about the dangers of climate change?” said Patrick McDonnell, who previously led Pennsylvania’s Department of Environmental Protection.

Goldman Sachs projects that US power demand will grow more than 2 per cent a year on average through the end of the decade, with data centres consuming around 8 per cent of the country’s electricity by 2030, up from roughly 3 per cent now.

The day Constellation announced in September that it would spend around $1.6 billion to restart Three Mile Island — a plant big enough to power more than 7,00,000 homes and employ upward of 700 people —the company’s stock rose 22 per cent.

Constellation anticipates that the reactor vessel won’t require any repairs, and the steam generators — costly equipment that help produce electricity — were replaced about 15 years ago. The company had them inspected in May and said it found no corrosion.

The main power transformers that connect the plant to the grid will need to be replaced at a cost of around $100 million. The plant is also getting a new name: the Crane Clean Energy Center.

“We know how to run this reactor, so as long as the equipment is in good shape, the level of complexity here is — I would describe it as significantly lower than building a new reactor,” Dominguez said.

NYTNS