Nobody believes it was ET phoning, but radio astronomers admit they do not have an explanation yet for a beam of radio waves that apparently came from the direction of the star Proxima Centauri.

“It’s some sort of technological signal. The question is whether it’s Earth technology or technology from somewhere out yonder,” said Sofia Sheikh, a graduate student at Pennsylvania State University, US, leading a team studying the signal and trying to decipher its origin. She is part of Breakthrough Listen, a $100 million effort funded by Yuri Milner, a Russian billionaire investor, to find alien radio waves. The project has stumbled on its most intriguing pay dirt yet.

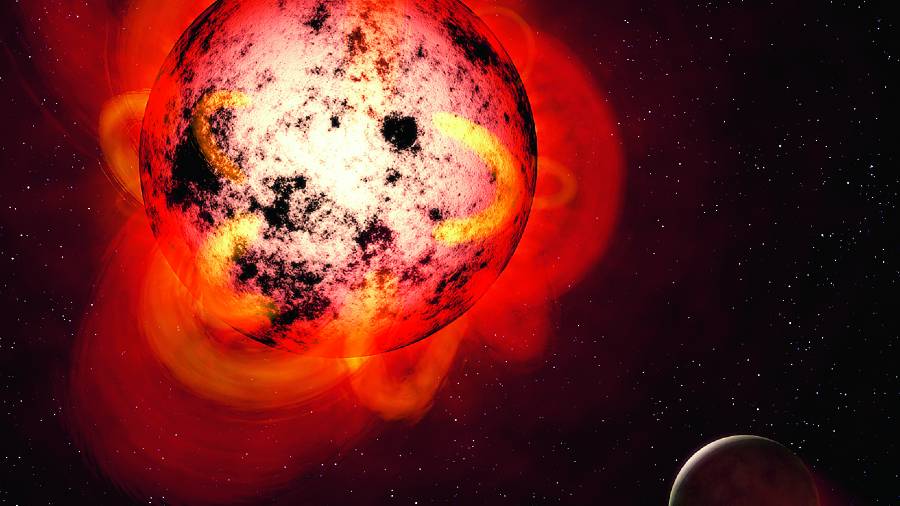

Proxima Centauri is an inviting prospect for “out yonder”.

It is the closest known star to the sun, only 4.24 light years from Earth. Proxima has at least two planets, one of which is a rocky world only slightly more massive than Earth and occupies the star’s so-called habitable zone, where temperatures should be conducive to water, the stuff of life, on its surface.

The radio signal itself, detected in 2019 and reported in The Guardian, is the stuff of dreams for alien hunters. It was a narrow-band signal with a frequency of 982.02 megahertz as recorded at the Parkes Observatory in Australia. Nature, whether an exploding star or a geomagnetic storm, tends to broadcast on a wide range of frequencies.

“The signal appears to only show up in our data when we’re looking in the direction of Proxima Centauri, which is exciting,” Sheikh said.

Practitioners of the hopeful field of the search for extraterrestrial intelligence, also known as Seti, say they have seen it all before.

“We’ve seen these types of signal before, and it’s always turned out to be RFI — radio frequency interference,” wrote Dan Werthimer, chief technologist at the Berkeley Seti Research Center who is not part of the Proxima Centauri study.

That thought was echoed by his Berkeley colleague Andrew Siemion, who is the principal investigator for Breakthrough Listen. “Our experiment exists in a sea of interfering signals,” he said.

“My instinct in the end is that it will be anthropogenic in origin,” he added. “But so far we can’t yet fully explain it.”

False alarms have been part of Seti since the beginning, when Frank Drake, then at Cornell, pointed a radio telescope in 1960 at a pair of stars, hoping to hear aliens’ radio waves. He detected what seemed to be a signal. It turned out to be a secret military experiment.

Breakthrough Listen was announced with fanfare by Milner and Stephen Hawking in 2015, sparking what Siemion called a renaissance.

The recent excitement began on April 29, 2019, when Breakthrough Listen scientists turned the Parkes radio telescope on Proxima Centauri to monitor the star for violent flares. It is a small star known as a red dwarf. These stars are prone to such outbursts, which could strip the atmosphere from a planet and render it unlivable.

In all, they recorded 26 hours of data. The Parkes radio telescope, however, was equipped with a new receiver capable of resolving narrow-band signals of the type Seti researchers seek. So in fall 2020, the team decided to search the data for such signals, a job that fell to Shane Smith, an undergraduate at Hillsdale College in Michigan, US, and an intern with Breakthrough.

The signal that surprised the team appeared five times on April 29 during a series of 30-minute windows in which the telescope was pointed in the direction of Proxima Centauri. It has not appeared since. It was a pure unmodulated tone, meaning it appeared to carry no message except the fact of its own existence.

The signal also showed a tendency to drift slightly in frequency during the 30-minute intervals, a sign that whatever the signal came from is not on the surface of Earth but often correlates with a rotating object.

But the drift does not match the motions of any known planets in Proxima Centauri. And, in fact, the signal — if it is real — might be coming from someplace beyond the Alpha Centauri system.

Sheikh, who expects to get her doctorate this coming summer, is leading the detective work. She got her bachelor’s degree at the University of California, Berkeley, US, intending to go into particle physics but found herself drifting into astronomy instead. She first heard about the Breakthrough Listen project and Seti on Reddit while she was looking for a new undergraduate research project.

“I would say we were extremely sceptical at first, and I remain sceptical,” she said about the putative signal. But she added that it was “the most interesting signal to come through the Breakthrough Listen programme”. The team hopes to publish its results early in 2021.

Over the years Seti astronomers have prided themselves on their ability to chase down the source of suspicious signals and eliminate them before word leaked out to the public.

“The public wants to know; we get that,” Siemion said. But, as he and Sheikh emphasise, they are not nearly done yet.“Frankly, there’s still a lot of analysis that we have to do to be confident that this thing is not interference,” Sheikh said.

Part of the problem is that the original observations were not done according to the standard Seti protocol. Normally, a radio telescope would point at a star or other target for five minutes and then “nod” slightly away from it for five minutes to see if the signal persisted.

In the Proxima observations, however, the telescope pointed for 30 minutes and then moved far across the sky (30° or so) for five minutes to a quasar the astronomers were using to calibrate the brightness of the star’s flares. Such a large swing might have taken the telescope away from the source of the radio interference.

If all else fails, Sheikh said, they will try to reproduce the results by replicating the exact movements of the Parkes telescope again on April 29, 2021.

NYTNS