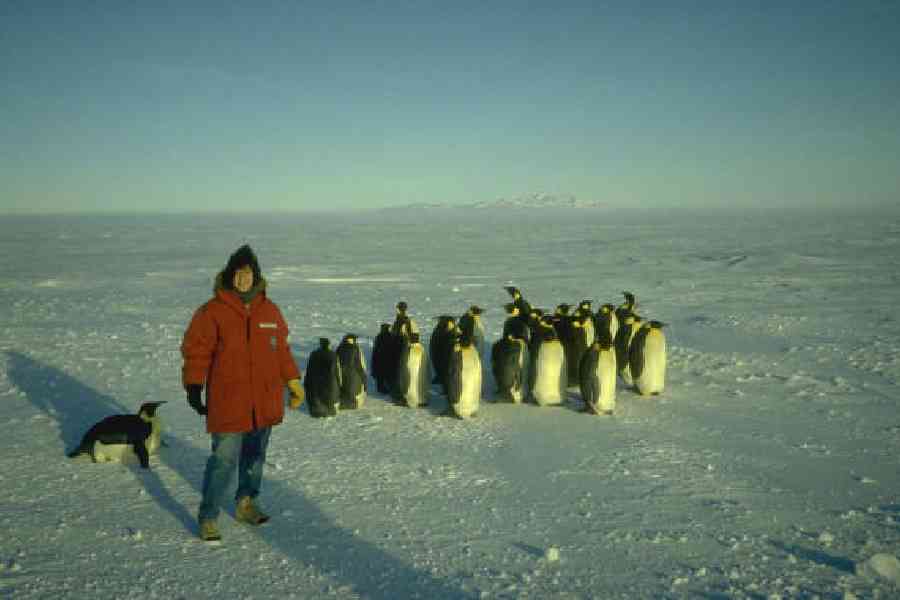

In the 1980s, groundbreaking atmospheric chemist Susan Solomon pioneered our understanding that the then-gaping hole in the ozone layer over Antarctica was caused by industrial chlorofluorocarbons, or CFCs.

A damaged ozone layer increases ultraviolet radiation on Earth, harming humans, ecosystems, plants and animals. Solomon’s work underpins the Montreal Protocol, which banned 99 per cent of ozone-depleting substances. Ratified by every country, the agreement is reversing the harms done to the ozone layer and is considered one of the most successful environmental treaties in history.

In her latest book, Solvable: How We Healed the Earth, and How We Can Do it Again, which was published recently, Solomon, who teaches at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the US, argues that we can learn from past environmental fights. Public awareness and consumer pressure can influence lawmakers, she says, and lead to positive change.

Here are excerpts from the interview.

q Why this book and why now?

People need to have some hope. We imagine that we never solve anything, that we have all these horrific problems and they’re just getting worse and worse and worse.

I’m not going to say we don’t have any problems. We do. But it’s really important to go back and look at how much we succeeded in the past and what are the common threads of those successes.

q The chemical companies’ pushback to reining in CFCs is arguably minimal compared to resistance from oil and gas companies to reducing greenhouse gas emissions. And the ozone issue didn’t have quite the same fervent political and polarised dissent from the public around it. Are these apples and apples comparisons?

Climate change is probably the heaviest lift we’ve ever attempted, just because energy is so embedded in the economy. Countries that use more fossil fuel energy are generally richer. There’s almost a linear relationship between how much you emit and how rich you are.

The key thing is how much technologies have changed. It follows from public opinion. It follows from the extent to which the public is actually demanding it. Sixty per cent of the American public believes the climate is changing and that it’s caused mainly by human activities, according to current polls. I would argue the paralysis hasn’t been as bad as people think it has been. And with CFCs, the companies actually did resist quite a bit.

q I recognise that there were ozone wars. But it was a smaller market and they could shift to other chemicals. This seems bigger and a bit scarier.

I think the smog issue was a better analogue. In 1970, when the Clean Air Act was passed, the auto industry was one of the most profitable industries in the US. They did not want to change.

They pushed back like crazy. But there was a massive amount of popular will. There was, therefore, bipartisan support. Ultimately, it happened because of popular support and clever technology forcing policies that could flow from that support.

q The US Supreme Court recently threw out the Chevron deference, which will almost certainly weaken or eliminate limits on water and air pollution, toxic chemical regulations, and policies that tackle climate change. So, how do we square that with the idea of hope for the planet?

I am scared about Chevron and was pretty appalled by that decision. It remains to be seen how much it’s really going to affect things, because if it moves forward the way the worst projections are suggesting, it will completely paralyse the courts. And that’s not viable, either.

At that point, I think Congress will have to go back and create a new law that will modify some form of Chevron. So, to me, the only question is: how long is that going to take? My gut feeling is it won’t be very long. It depends on your definition of long.

I think, fortunately, in a way, the globalisation of economies is going to continue to put pressure on America to meet standards in other parts of the world.

q Your book is called Solvable. We have data scientist Hannah Ritchie, who wrote Not the End of the World. We have marine biologist Ayana Elizabeth Johnson, whose books include All We Can Save. And we have climate scientist Katharine Hayhoe highlighting solutions. I don’t want to be gender essentialist, but do you think there’s something there? When I think of the scariest books about climate change, they tend to have been written by men, to be frank.

I think women are actually pretty good problem solvers. So, in all of those cases, they’re thinking about how this thing can actually end up being solved. But as a scientist, I have to say we’re dealing with a small number of statistics here.

NYTNS