When Apple held a corporate retreat in California’s Carmel Valley five years ago to discuss its next major product, design chief Jony Ive captivated a room of their 100 top executives with a concept video as polished as an Apple commercial.

The video showed a man in a London taxi donning an augmented reality headset and calling his wife in San Francisco. “Would you like to come to London?” he asked. Soon, the couple were sharing the sights of London through the husband’s eyes.

The video excited executives about the possibilities of Apple’s next business-altering device: a headset that would blend the digital world with the real one.

But now, as the company prepares to introduce the headset in June, enthusiasm has given way to scepticism, said eight current and former employees, who requested anonymity. There are concerns about the device’s roughly $3,000 price, doubts about its utility and worries about its unproven market.

That dissension has been a surprising change inside a company where employees have built devices — from the iPod to the Apple Watch — with the single-mindedness of a moon mission.

Some have defected from the project because of their doubts about its potential. Others have been fired over the lack of progress with some aspects of the headset, including its use of Apple’s Siri voice assistant.

Even leaders have questioned the product’s prospects. It has been developed at a time when morale has been strained by a wave of departures from the company’s design team, including Ive, who left Apple in 2019.

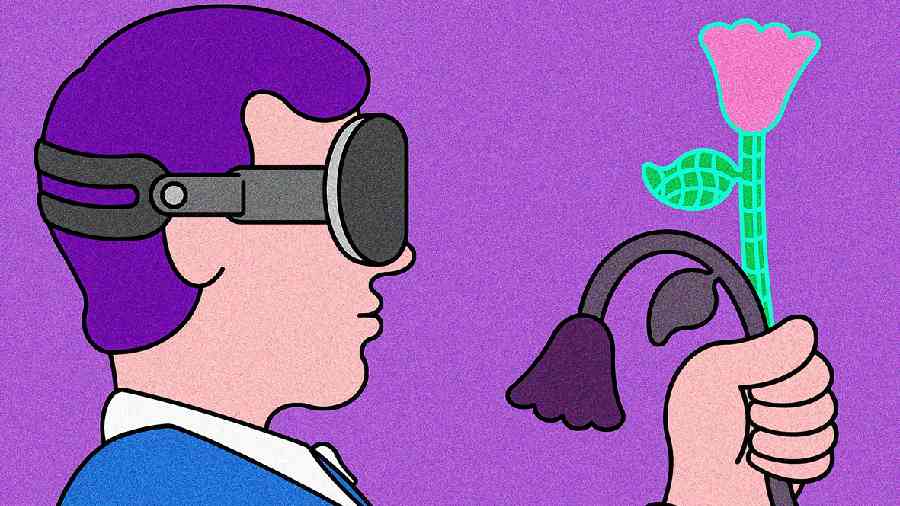

Apple’s headset is considered a bellwether for virtual and augmented reality. For more than a decade, tech leaders have been hyping it as the next wave of computing after the smartphone. CEO Tim Cook told university students last year that in the near future “You’ll wonder how you lived your life without augmented reality, just like today you wonder: how did people like me grow up without the Internet?”

But the road to delivering augmented reality has been littered with failures, false starts and disappointments, from Google Glass to Magic Leap and from Microsoft’s HoloLens to Meta’s Quest Pro. Apple is considered a potential saviour thanks to its success in combining new hardware and software to create revolutionary devices.

Meta has ploughed billions of dollars into trying to build a virtual reality business. The experience has been humbling. It has sold about 20 million of its $400 Quest 2 headsets since 2020 and recently cut the price of the Quest Pro, its premium device, to $1,000 from $1,500.

By comparison, Apple sells over 200 million iPhones annually with an average selling price of over $800.

Unlike the iPhone, which incorporated many existing technologies, VR is requiring Apple and others to design new chips and wearable displays, said Matthew Ball, author of The Metaverse: And How It Will Revolutionize Everything.

Seeking to define a nascent market is an aberration for Apple.

“Apple is good at coming into a market when the market is already established and changing that market,” said Carolina Milanesi, a consumer tech analyst for the research firm Creative Strategies. “This is not the case for Apple VR and XR. There’s still a lot of learning.”

The headset features a carbon fibre frame, cameras to capture the real world and two 4K displays that can render everything from applications to movies. Users can turn a “reality dial” on the device to increase or decrease real-time video.

Because it won’t fit over glasses, the company has plans to sell prescription lenses for the displays to people who don’t wear contacts.

Apple has focussed on making it excel for videoconferencing and spending time with others in a virtual world. The company has called the device’s signature application “copresence”, a word designed to capture the experience of sharing a real or virtual space with someone in another place. It is akin to what Mark Zuckerberg calls the “metaverse”.

Milanesi said Apple’s experimental approach with the goggles appeared to be more like its execution of the Apple Watch than its introduction of the iPhone. Apple initially portrayed the watch as a miniature extension of an iPhone. After learning what consumers were doing with the watch, the company marketed it more as a fitness accessory akin to a Fitbit.

“It’s not very Apple-like,” Milanesi said. “But then Apple is a very, very different company.”

NYTNS