During a workshop in the fall at the Vatican, Stanislas Dehaene, a cognitive neuroscientist with the Collège de France, gave a presentation chronicling his quest to understand what makes humans — for better or worse — so special.

Dehaene has spent decades probing the evolutionary roots of our mathematical instinct; this was the subject of his 1996 book, The Number Sense: How the Mind Creates Mathematics. Lately, he has zeroed in on a related question: What sorts of thoughts, or computations, are unique to the human brain? Part of the answer, Dehaene believes, might be our seemingly innate intuitions about geometry.

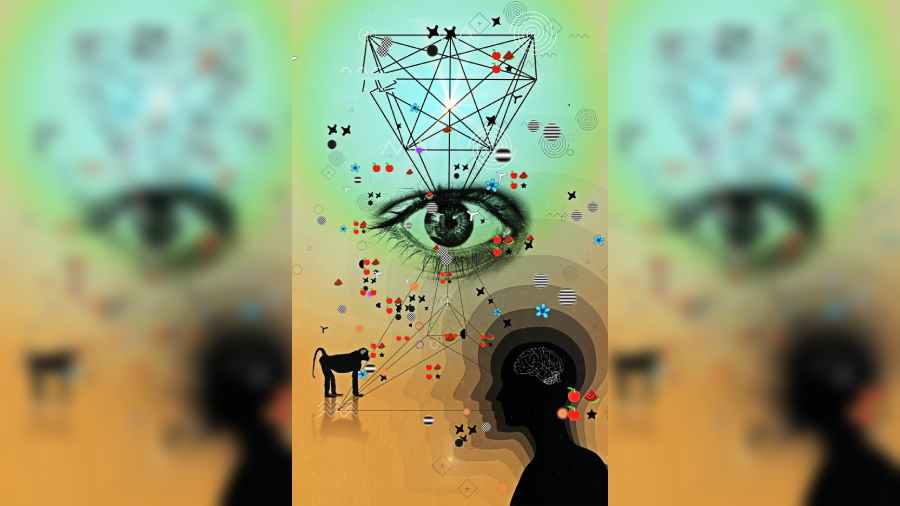

Organised by the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, the Vatican workshop addressed the subject “Symbols, Myths and Religious Sense in Humans Since the First” — that is, since the first humans emerged a couple of million years back. Dehaene began his slideshow with a collage of photographs showing symbols engraved in rock — scythes, axes, animals, gods, suns, stars, spirals, zigzags, parallel lines, dots. Some of the photos he took during a trip to the Valley of Marvels in southern France. These engravings are thought to date back to the Bronze Age, from roughly 3300 BC to 1200 BC; others were 70,000 and 5,40,000 years old. He also showed a photo of a “biface” stone implement — spherical at one end, triangular at the other — and he noted that humans sculpted similar tools 1.8 million years ago.

For Dehaene, it is the inclination to imagine — a triangle, the laws of physics, the square root of negative 1 — that captures the essence of being human. “The argument I made in the Vatican is that the same ability is at the heart of our capacity to imagine religion,” he recalled recently.

He acknowledged it is no small leap from imagining a triangle to devising religion. (His own intellectual trajectory entailed a degree in mathematics and a master’s in computer science before becoming a neuroscientist.) Nevertheless, he said, “This is what we have to explain: suddenly there was an explosion of new ideas with the human species.”

Human or baboon?

Last spring, Dehaene and his doctoral student Mathias Sablé-Meyer published, with collaborators, a study that compared the ability of humans and baboons to perceive geometric shapes. The team wondered: what was the simplest task in the geometric domain — independent of natural language, culture, education — that might reveal a signature difference between human and non-human primates? The challenge was to measure not merely visual perception but a deeper cognitive process.

This line of investigation has a long history, yet is perennially fascinating, according to Moira Dillon, a cognitive scientist at New York University, US, who has collaborated with Dehaene on other research. Plato believed that humans were uniquely attuned to geometry; linguist Noam Chomsky has argued that language is a biologically rooted human capacity. Dehaene aims to do for geometry what Chomsky did for language. “Stan’s work is truly innovative,” Dillon said, noting that he uses state-of-the-art tools such as computational models, cross-species research, artificial intelligence and functional MRI neuroimaging techniques.

In the experiment, subjects were shown six quadrilaterals and asked to detect the one that was unlike the others. For all the human participants — French adults and kindergartners as well as adults from rural Namibia with no formal education — this “intruder” task was significantly easier when either the baseline shapes or the outlier were regular, possessing properties such as parallel sides and right angles.

The researchers called this the “geometric regularity effect”, and they hypothesised — it’s a fragile hypothesis, they admit — that this might provide, as they noted in their paper, a “putative signature of human singularity”.

With the baboons, regularity made no difference, they found. Twenty-six baboons — including Muse, Dream and Lips — participated in this aspect of the study, which was run by Joël Fagot, a cognitive psychologist at Aix-Marseille University, France.

“The results are striking, and there seems indeed a difference between the perception of shapes by humans and baboons,” Frans de Waal, a primatologist at Emory University, US, said in an email. “Whether this difference in perception amounts to human ‘singularity’ would have to await research on our closest primate relatives, the apes,” de Waal said. “It is also possible, as the authors argue (and reject), that humans live in an environment where right angles matter, whereas baboons do not.”

Building on research originating in the 1980s, they propose a “language of thought” to explain how geometric shapes might be encoded in the mind. And in a fittingly circuitous twist, they find inspiration in computers.

“We postulate that when you look at a geometric shape, you immediately have a mental programme for it,” Dehaene said. “You understand it, inasmuch as you have a programme to reproduce it.” In computational terms, this is called programme induction. “It’s not trivial,” he said. “It’s a big problem in artificial intelligence — to induce a programme to do a certain thing from its input and output. In this case, it’s just an output, which is the drawing of the shape.”

Language is often assumed to be the quality that demarcates human singularity, Dehaene noted, but perhaps there is something that is more basic, more fundamental.

“We are proposing that there are languages — multiple languages — and that, in fact, language may not have started as a communication device, but really as a representation device, the ability to represent facts about the outside world,” he said. “That’s what we are after.”

NYTNS