A year ago, Nasa’s Perseverance rover was accelerating to a collision with Mars, nearing its destination after a 290-million-mile, seven-month journey from Earth.

Last February 18, the spacecraft carrying the rover pierced the Martian atmosphere at 13,000 mph. In just seven minutes — what Nasa engineers call “seven minutes of terror” — it had to pull off a series of manoeuvers to place Perseverance gently on the surface.

Given the minutes of delay for radio communications to crisscross the solar system, the people in mission control at Nasa’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, US, were merely spectators that day. If anything had gone wrong, they would not have had any time to attempt a fix, and the $2.7 billion mission — to search for evidence that something once lived on the red planet — would have ended in a newly excavated crater.

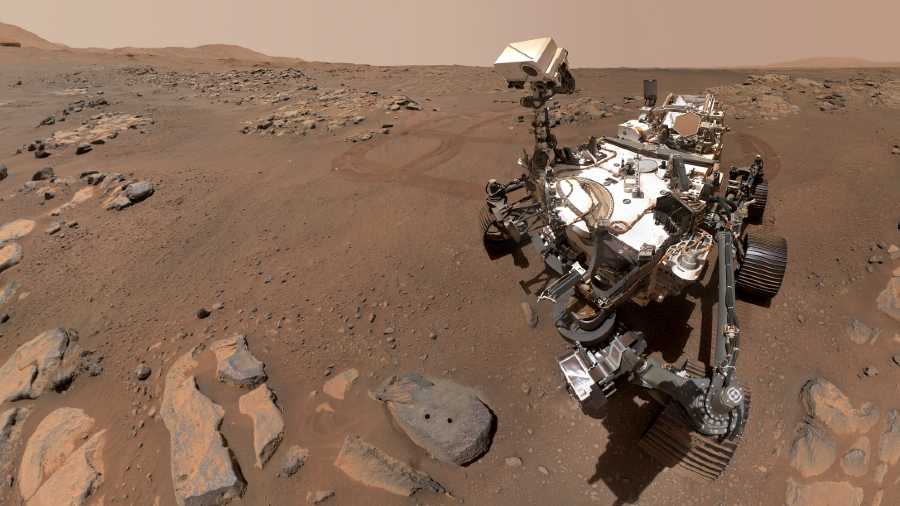

But Perseverance performed perfectly, sending home exhilarating video footage as it landed. And Nasa added to its collection of robots exploring Mars. “The vehicle itself is just doing phenomenally well,” said Jennifer Trosper, project manager for Perseverance. Twelve months later, Perseverance is nestled within a 28-mile-wide crater known as Jezero.

After months of scrutinising the crater floor, the mission team is preparing for the main scientific event: investigating a dried-up river delta along the west rim of Jezero.

That is where scientists expect to find sedimentary rocks that are most likely to contain blockbuster discoveries, maybe even signs of ancient Martian life — if any ancient life ever existed on Mars.

“Deltas are, at least on Earth, habitable environments,” said Amy Williams, a geology professor at the University of Florida, US, and a member the Perseverance science team. “There’s water. There’s active sediment being transported from a river into a lake.”

Such sediments can preserve carbon-based molecules that are associated with life. “That’s an excellent place to look for organic carbon,” Williams said. “So hopefully, organic carbon that’s indigenous to Mars is concentrated in those layers.”

Perseverance landed not much more than a mile from the delta. Even at a distance, the rover’s eagle-eyed camera could make out the expected sedimentary layers. There were also boulders, some as large as cars, sitting on the delta, rocks that were washed into the crater.

“This all tells a fascinating story,” said Jim Bell, a planetary scientist at Arizona State University in the US.

The data confirm that what orbital images suggested was a river delta is indeed that and that the history of water here was complex. The boulders, which almost certainly came from the surrounding highlands, point to episodes of violent flooding at Jezero. “It wasn’t just slow, gentle deposition of fine grained silt and sand and mud,” said Bell, who serves as principal investigator for the sophisticated cameras mounted on Perseverance’s mast.

Mission managers had originally planned to head directly to the delta from the landing site. But the rover set down in a spot where the direct route was blocked by sand dunes that it could not cross.

The geological formations to the south intrigued them. “We landed in a surprising location, and made the best of it,” said Kenneth Farley, a geophysicist at the California Institute of Technology, US, who serves as the project scientist leading the research.

Because Jezero is a crater that was once a lake, the expectation was that its bottom would be rocks that formed out of the sediments that settled to the bottom.

But at first glance, the lack of layers meant “they did not look obviously sedimentary,” said Kathryn Stack Morgan of Nasa’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and who is the deputy project scientist. Nothing clearly suggested they were volcanic in origin either.

As the scientists and engineers contemplated whether to circle around to the north or to the south, the team that built a robotic helicopter named Ingenuity got to try out their creation.

On April 18, Ingenuity rose to a height of 10 feet, hovered for 30 seconds and then descended back to the ground. The flight lasted 39.1 seconds. Over the next weeks, Ingenuity made four more flights of increasing time, speed and velocity.

That was supposed to be the end of Ingenuity’s mission. Perseverance was to leave it behind and head off on its research.

But Nasa decided five flights were not enough. When Perseverance set off to explore the rocks to the south, Ingenuity went along, scouting the terrain ahead of the rover. That helped avoid wasting time driving to unexceptional rocks that had looked potentially interesting in images from orbit. “We sent the helicopter and saw the images, and it looked very similar to where we were,” Trosper said. “And so we chose not to drive.” The helicopter just completed its 19th flight, and it remains in good condition.

Once Perseverance gets to the delta, the most electrifying discovery would be images of what looked to be microscopic fossils. It is unlikely Perseverance will see anything that is unequivocally a remnant of a living organism. That is why it is crucial for the rocks to be brought to Earth for closer examination.

Bosak does not have a strong opinion on whether there was ever life on Mars.

“We are really trying to peer into the time where we have very little knowledge,” she said. “We have no idea when chemical processes came together to form the first cell. And so we may be looking at something that was just learning to be life.”

NYTNS