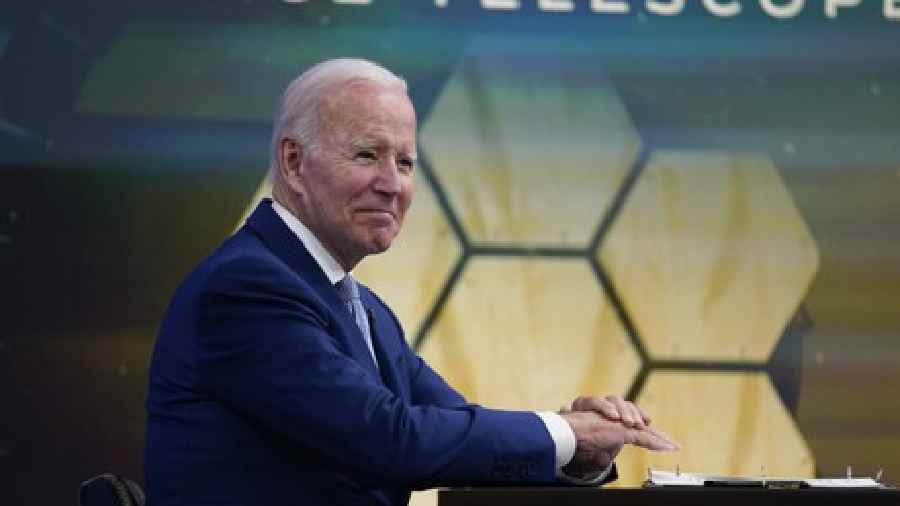

US President Joe Biden unveiled an image that NASA and astronomers hailed as the deepest view yet into our universe’s past in a brief event at the White House on Monday evening.

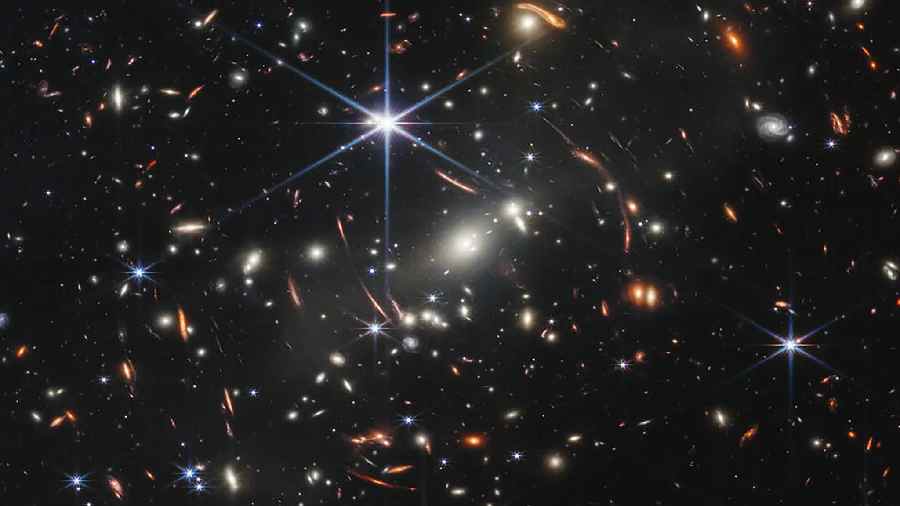

The image, taken by the James Webb Space Telescope — the largest space telescope ever built — showed a distant patch of sky in which fledgling galaxies were burning their way into visibility just 600 million years after the Big Bang.

“This is the oldest documented light in the history of the universe from 13 billion — let me say that again, 13 billion — years ago,” Biden said. The president, who apologised for beginning the event tardily, praised NASA for its work that enabled the telescope and the imagery it will produce.

“We can see possibilities no one has ever seen before,” Biden said. “We can go places no one has ever gone before.”

Biden’s announcement served as a teaser for the telescope’s big cosmic slideshow scheduled for Tuesday night (IST) when scientists reveal what the Webb has been looking at for the past six months.

For Biden, the reveal of the images was also a chance to engage directly with an event that will almost certainly stir wonder and pride among Americans — at a time when his approval ratings have plummeted as voters recoil at high food and gasoline prices and Democrats question his ability to fight for gun control and abortion rights.

In a setting in the White House’s South Auditorium that evoked scenes from the bridge of a starship on “Star Trek,” Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris were joined by Alondra Nelson, the acting director of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy; Bill Nelson, the former Florida senator appointed NASA administrator by Biden; and Jane Rigby, an operations project scientist for the Webb telescope. Each sat at small, widely spaced desks in front of a large screen where other NASA officials appeared. The screen gave way to the cosmic image, which was speckled with tiny dots of galaxies and drew applause from the far end of the room.

Nelson, the NASA chief, touted the telescope’s scientific potential at the White House event.

“We are going to be able to answer questions that we don’t even know what the questions are yet,” he said. When he added that the technology could determine whether other planets were habitable, Biden responded with a “Whoa.”

As the ceremony ended and the reporting pool was escorted from the room, Biden was heard to say, “I wonder what the press are like in those other places.”

One of the most ambitious of the Webb telescope’s missions is to study some of the first stars and galaxies that lit up the universe soon after the Big Bang 14 billion years ago. Although Monday’s snapshot might not have reached that far, it proved the principle of the technique and hinted at what more is to come from the telescope’s scientific instruments, which astronomers have waited decades to bring online.

As the telescope “gathers more data in the coming years, we will see out to the edge of the Universe like never before,” said Priyamvada Natarajan, of Yale University, an expert on black holes and primeval galaxies, in an email from India,

She added, “It is beyond my wildest imagination to be alive when we get to see out to the edge of black holes, and the edge of the universe.”

President Joe Biden listens during a briefing from NASA officials about the first images from the James Webb Space Telescope, the largest space telescope ever built, in the South Court Auditorium on the White House complex, in Washington, Monday, July 11, 2022. On Monday, humanity got its first glimpse of what the observatory in space has been seeing: a cluster of early galaxies. New York Times

What image NASA and Biden showed?

On Friday, NASA released a list of five subjects that Webb had recorded with its instruments. But Biden showed off one of them at the White House on Monday.

The image goes by the name of SMACS 0723. It is a patch of sky visible from the Southern Hemisphere on Earth and often visited by Hubble and other telescopes in search of the deep past. It includes a massive cluster of galaxies about 4 billion light-years away that astronomers use as a kind of cosmic telescope. The cluster’s enormous gravitation field acts as a lens, warping and magnifying the light from galaxies behind it that would otherwise be too faint and far away to see.

Thomas Zurbuchen, NASA’s associate administrator for space science, described this image as the deepest view yet into the past of our cosmos.

Marcia Rieke of the University of Arizona, who led the building of NIRCam, one of the cameras on the Webb telescope that took the picture, said, “This image will not hold the ‘deepest’ record for long but clearly shows the power of this telescope.”

What about the rest of the images?

NASA will show other pictures at 10:30 a.m. ET Tuesday (8.00Pm IST) in a live video stream you can watch on NASA TV or YouTube. They will be shown off at the Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

The pictures constitute a sightseeing tour of the universe painted in colors no human eye has seen — the invisible rays of infrared, or heat radiation. A small team of astronomers and science outreach experts selected the images to show off the capability of the new telescope and to knock the socks off the public.

There is the Southern Ring Nebula, a shell of gas ejected from a dying star about 2,000 light-years from here, and the Carina Nebula, a huge swirling expanse of gas and stars including some of the most massive and potentially explosive star systems in the Milky Way.

Yet another familiar astronomical scene is Stephan’s Quintet, a tight cluster of galaxies about 290 million light-years from here in the constellation Pegasus.

The team will also release a detailed spectrum of an exoplanet known as WASP-96b, a gas giant half the mass of Jupiter that circles a star 1,150 light-years from here every 3.4 days. Such a spectrum is the sort of detail that could reveal what is in that world’s atmosphere.

Why has it taken so long to share Webb’s first images?

Getting to space on Christmas Day last year was just the first step for the James Webb Space Telescope.

The spacecraft has been orbiting the second Lagrange point, or L2, about 1 million miles from Earth since Jan. 24. At L2, the gravitational pulls of the sun and the Earth keep Webb’s motion around the sun in synchronization with Earth’s.

Before it got there, pieces of the telescope had to be carefully unfolded: the sun shield that keeps the instruments cold so it can precisely capture faint infrared light, the 18 gold-plated hexagonal pieces of the mirror.

For the astronomers, engineers and officials watching on Earth, the deployment was a tense time. There were 344 single-point failures, meaning if any of the actions had not worked, the telescope would have ended as useless space junk. They all worked.

The telescope’s four scientific instruments also had to be turned on. In the months following the telescope’s arrival at L2, its operators painstakingly aligned the 18 mirrors. In April, the Mid-Infrared Instrument, or MIRI, which requires the coldest temperatures, was cooled to minus 447 degrees Fahrenheit, and scientists could begin a final series of checks on it. Once these and other steps were done, the science could begin.

How does the Webb compare with the Hubble telescope?

The Webb telescope’s primary mirror is 6.5 meters (about 21 feet) in diameter, compared with Hubble’s, which is 2.4 meters, giving Webb about seven times as much light-gathering capability and thus the ability to see further out in space and so deeper into the past.

Another crucial difference is that Webb is equipped with cameras and other instruments sensitive to infrared, or “heat,” radiation. The expansion of the universe causes the light that would normally be in wavelengths that are visible to be shifted to longer infrared wavelengths that are normally invisible to human eyes.

New York Times News Service