One is massive, spherical and unmoving. The other is tiny, has a tail and never stops swimming. Yet the union of egg and sperm is critical for every sexually reproducing animal on Earth.

Exactly how that union occurs has long been a mystery. A study published in the Cell relied on Nobel Prize-honoured artificial intelligence technology to show that an interlocked bundle of three proteins is the key that lets sperm and egg bind together. That crucial bundle is shared by animals as distantly related as fish and mammals, and most likely by humans.

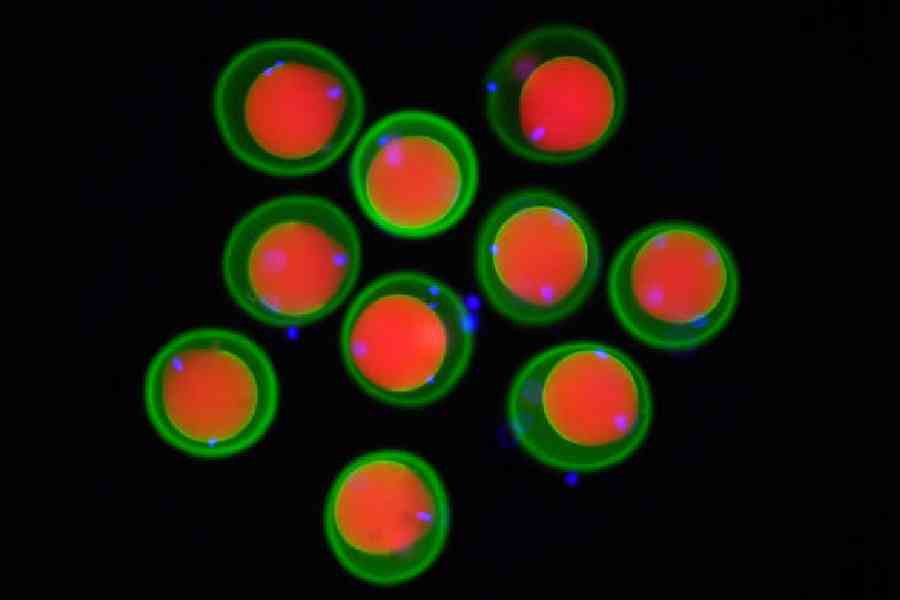

For nearly all animals on Earth, life begins with a sperm cell making its way to an egg’s cell membrane. Somehow, the two cells recognise each other and bind together. Then, in a flash, the sperm head passes into the egg, as if stepping through a door. Now the fused cell is a zygote and ready to grow into a new animal.

In earlier research, scientists had found four proteins on mammal sperm that are also present on fish sperm and are needed for fertilisation. But no one knew whether they might work as a team to enter an egg, or how.

In the new study, Andrea Pauli, a molecular and developmental biologist at the Research Institute of Molecular Pathology in Vienna, Austria, and collaborators across several institutions asked how sperm proteins might team up during fertilisation.

The researchers relied on AlphaFold, a technology that shared the recent Nobel Prize in chemistry. It uses AI to predict the shape of a protein. With it, the team could compare the four sperm proteins shared across mammals and fish against a library of about 1,400 other proteins found on cell surfaces in zebrafish testes, looking for potential partners.

“We wanted to find something that we knew would be at the right place and at the right time,” said Victoria Deneke, a postdoctoral researcher in Pauli’s lab.

Even for AlphaFold, this was a challenge. “It was running for more than two weeks,” Deneke said, monopolising the campus’ computing resources.

“Other people at the institute were not so happy,” Pauli added.

Finally, AlphaFold predicted that two of the original shared sperm proteins would bind to each other, along with a third protein that was previously unknown, creating a team of three.

Lab experiments confirmed the programme’s guess: male zebrafish missing the newly discovered third protein were infertile, as were male mice. Their sperm swam normally but couldn’t fuse with an egg. The scientists also found biochemical evidence that the three sperm proteins were working as a unit, both in zebrafish and humans. It’s likely that the same crucial bundle exists in many — or all — animals with a backbone, Pauli said.

She described the sperm protein bundle as a key, which fits with a lock on an egg cell. In fish, that lock is a protein named Bouncer — appropriate, as the sperm can’t enter the egg without it.

Earlier research also identified a lock molecule in mammal eggs. Oddly, though, the mammalian lock isn’t Bouncer. It’s an unrelated protein called Juno.

That means somewhere in history animals evolved different egg proteins to bind the sperm protein bundle. That presents a mystery, Pauli said: the lock has changed, yet somehow, “the key on the sperm stayed the same”.

Amber Krauchunas, a reproductive biologist at the University of Delaware, US, who was not involved in the new research, called the new paper “really exciting”.

Earlier this year, a different research group independently used AlphaFold and predicted the existence of the same three-protein bundle in mammals. “The fact that two independent groups came to the same conclusions certainly increases our confidence in the results,” Krauchunas said.

Even so, she said, “more work certainly remains to uncover the mysteries of fertilisation”. For example, some sperm proteins are known to be shared across mammals and fish but aren’t part of this bundle; what are they doing?

“This is such a fundamental question with so few molecular answers,” Pauli said. “It’s amazing.”

NYTNS