The message emblazoned on a walkway window at the airport in Burlington, Vermont, US, is a startling departure from the usual tourism posters and welcome banners:

“Addiction is not a choice. It’s a disease that can happen to anyone.”

The statement, part of a public service campaign in a community assailed

by drug use, is intended to reduce stigma and encourage treatment.

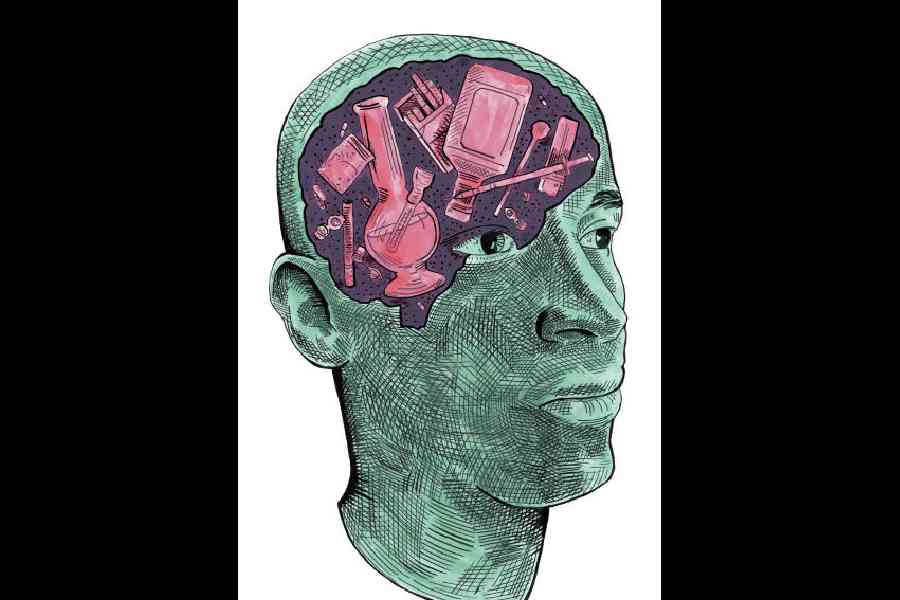

For decades, medical science has classified addiction as a chronic brain disease, but the concept has always been something of a hard sell to a sceptical public. That is because, unlike diseases such as Alzheimer’s, bone cancer or Covid, personal choice does play a role, both in starting and ending drug use. The idea that those who use drugs are themselves at fault has recently been gaining fresh traction, driving efforts to toughen criminal penalties for drug possession and to cut funding for syringe-exchange programmes.

But now, even some in the treatment and scientific communities have been rethinking the label of chronic brain disease.

In July, behaviour researchers published a critique of the classification, which they said could be counterproductive for patients and families.

“I don’t think it helps to tell people they are chronically diseased and therefore incapable of change,” said Kirsten E. Smith, an assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioural sciences at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, US, and a co-author of the paper, published in the journal Psychopharmacology. “Then what hope do we have? The brain is highly dynamic, as is our environment.”

The recent scientific criticisms are driven by an ominous urgency: despite addiction’s long-standing classification as a disease, the deadly public health disaster has only worsened.

Almost no one is calling for entirely scrapping the disease model. Few dispute that constant use of stimulants such as methamphetamine and opioids like fentanyl have a detrimental effect on the brain.

But some scientists argue that brain-centric disease characterisations of addiction do not sufficiently incorporate factors such as social environment and genetics. In the recent critique, researchers contended that rather than emphasising the brain’s brokenness in perpetuity, an addiction definition should include the motivation or context in which the person chose to use drugs.

That choice, they said, is often about seeking an escape from intractable conditions such as a fraught home, undiagnosed mental health and learning disorders, bullying or loneliness. Generations of family addiction further tip the scales toward substance use.

And in many environments, they added, drugs are simply more readily available than healthier, rewarding options, including education and jobs.

Choosing drugs could then be understood not as a moral failing but as a form of decision-making, with its own bleak logic.

In combination with medications that subdue opioid cravings, therapists could help patients identify the reasons that led them to use drugs and then encourage them to make choices that result in meaningful, sustained rewards.

In a 2021 paper in the journal Neuropsychopharmacology, Dr Markus Heilig, a former research director at the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, defended the brain disease diagnosis, saying evidence has been amply documented. But his paper acknowledges, “Brain-centric accounts of addiction have for a long time failed to pay enough attention to the inputs that social factors provide to neural processing behind drug seeking and taking.”

In clinical practice, the term “addiction” is becoming increasingly nuanced. John F. Kelly, a psychologist and professor of addiction psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, US, defines addiction as “a severe substance use disorder that is at the point where there are lots of changes in the prefrontal cortex as well as deeper areas of the brain” that regulate emotion and behaviour.

But only a small minority of people meet that criteria, he said. “Even within that severe range, there’s a lot of different degrees of impairment that can occur,” Kelly added. Genetics can exacerbate the severity of the response.

In disputing the characterisation of addiction as a disease marked by compulsive or relapsing use, a few experts have argued that some drug and alcohol users can quit without treatment and even return to occasional safe use.

Compounding the modern confusion about the nature of addiction, psychiatry keeps refining criteria for what it labels “substance use disorder”. In the current edition of its diagnostic manual, the DSM-V, a person has a mild disorder if they meet at least two of 11 symptoms mentioned. The more the symptoms, the greater the severity of the disorder.

Research on drug use gained momentum in the 1970s. By 1997, Alan I. Leshner, then the head of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, published a foundational position paper, “Addiction Is a Brain Disease, and It Matters.”

To the public, policymakers and even healthcare workers, he wrote, “Addiction as a chronic, relapsing disease of the brain is a totally new concept.”

But he did not overlook contributing factors. “Not only must the underlying brain disease be treated, but the behavioural and social cue components must also be addressed,” he wrote.

His much-cited research summary had a powerful, positive effect. The brain-disease designation would stimulate funding for research, be used to expand insurance coverage for treatment and prompt changes in public policy and criminal law, where newly minted drug courts — now increasingly called “recovery courts” — urged defendants into treatment. The brain-disease framework would eventually be adopted by mainstream medicine, including the surgeon-general.

And it offered patients and families a building block toward compassion as well as ways to counter ubiquitous scorn.

The model continues to hold value, said Dr Nora Volkow, who now leads the institute. She refers to addiction as “a chronic, treatable medical condition”.

NYTNS