It has been a transportation dream for more than 150 years. In the 1870s, a test system used a pneumatic vacuum tube to propel people under Manhattan from Warren Street to Murray Street.

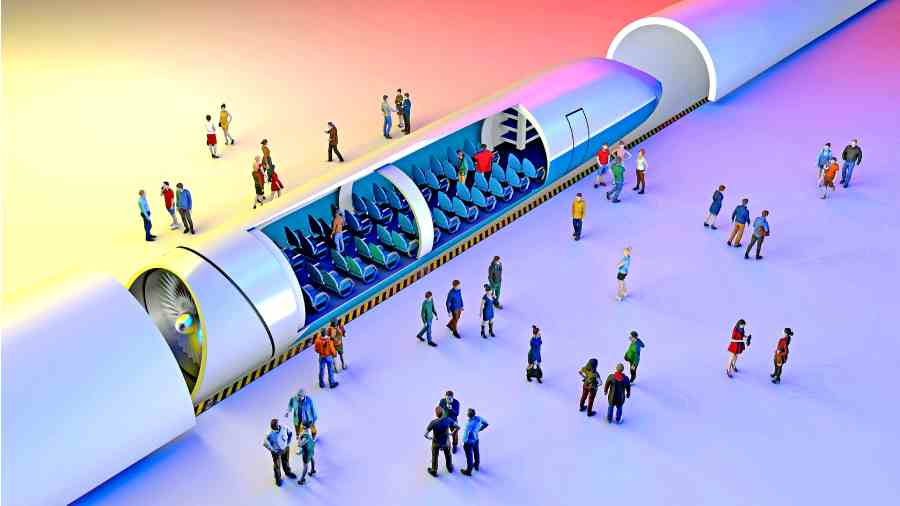

By the 2010s, a new and much-improved version of vacuum tube technology called hyperloop promised to transport people not a few blocks, but between cities at speeds that rival air travel, moving magnetically levitated passenger pods at more than 600 mph.

Yet while companies have raised hundreds of millions of dollars to design and construct hyperloop systems — with projects in India, the Netherlands, Saudi Arabia and the United States — the technology remains an aspiration.

The concept got a boost in November 2020, when Virgin Hyperloop (then known as Hyperloop One) became the first company to move people using the technology. In its hyperloop test facility outside Las Vegas in the US, two employees travelled in a full-scale vacuum tube at 107 mph on a 500-metre (about 1,640-foot) test track. Although a far cry from the promise of 600 mph, the test, company executives said at the time, proved that the system could work.

“This is the first new form of mass transportation in over 100 years,” said Jay Walder, the company’s CEO at the time. The test passengers “are real people. This test shows that we are a culture of safety.”

Yet barely a year later, the company retrenched and scaled back its ambitions. Walder departed in February 2021; Josh Giegel, his successor as CEO and the company’s co-founder, followed last October. And in January, Virgin Hyperloop fired half its staff (more than 100 employees), stopped the development of a certification centre in West Virginia, US, put on hold the development of a route in India and pivoted its focus to cargo transport.

The company’s downsising and shift in focus are emblematic of the difficulties facing the hyperloop industry, transportation analysts say.

“Time and again, you see technological innovations attracting a lot of investment, and you can make a lot of money during the hype cycle,” said Juan Matute, deputy director of the Institute of Transportation Studies at UCLA, US. However, the technology doesn’t anticipate the significant technical challenges associated with creating an entirely new infrastructure. “Then interest wanes,” Matute said.

While such challenges might eventually be solved, some industry observers believe that regulatory, financial and political hurdles may doom the hyperloop as a viable high-speed alternative to air travel.

The central impediment: while new types of transport such as electric vehicles can easily be integrated into the existing system of roads, a hyperloop system would require creating an entire infrastructure. That means constructing miles-long systems of tubes and stations, acquiring rights of way, adhering to government regulations and standards, and avoiding changes to the ecology along its routes.

A number of hyperloop companies continue to work toward creating workable systems. In some cases, the Covid-19 pandemic slowed progress as governments turned toward more pressing issues. That’s why Virgin Hyperloop stopped work on its India project, said a spokesperson for DP World, a global supply chain logistics company and Virgin Hyperloop’s majority owner.

The halt of the project was “more of a regulatory and political issue. They had a shift in priorities,” said Daniel Van Otterdijk, group chief communications officer for DP World.

TransPod, based in Toronto, Canada, had planned to build a half-scale-sized hyperloop test track in Limoges, France, by 2019, but that was delayed; construction has started, said Sebastien Gendron, the company’s CEO and co-founder. “The plan is to make it 3 kilometres in length,” he said, “but it may be shorter.”

The company is also planning an aboveground system connecting the Calgary and Edmonton airports in Canada. Its first phase will be a test track running 5 kilometres from Edmonton. The company expects that to be completed by 2025, followed by a two-year certification process, allowing it to begin construction in Calgary by 2027.

The company envisions a system that will carry cargo and, eventually, people. “Not having a system for passengers would be stupid,” Gendron said. Still, he acknowledges that funding continues to be a major obstacle.

Indeed, a passenger-viable system would cost considerably more than a cargo-centric one. With people on board, track curves would have to be less angled to avoid discomfort, and safety guarantees would need to be paramount to ensure that sabotage or a system failure in the tube does not cause a catastrophic loss of pressure or lack of oxygen for those travelling.

Others see a hyperloop system designed solely to transport cargo as a solution in search of a problem.

“I don’t know of any case where cargo is in such a hurry,” said Carlo van de Weijer, director of smart mobility at the Eindhoven University of Technology in the Netherlands. “Most cargo takes two-and-a-half weeks to come from China. Why do you suddenly need to move it somewhere in 10 minutes? We’re perfectly satisfied with a truck that goes 50 miles per hour.”

Van de Weijer believes the “immense” infrastructure costs associated with the hyperloop — including the construction of tubes, tunnels and pillars — do not justify the expense.

“Eventually, we’ll have sustainable fuels for airplanes,” he said. “Saying we should build a hyperloop system is like saying because Netflix streaming uses too much energy, we should invest in VCRs. We should make streaming more efficient.”

NYTNS