Changes in human diet over the centuries gave rise to f-words, says a study that provides the strongest evidence yet for a theory that diet-induced changes in teeth shaped humans’ capacity to make certain speech sounds.

The study by an international team of researchers has used evidence from linguistics, anatomy and anthropology to show how diet-induced changes in the human bite spawned new so-called labiodental speech sounds including “f”, “v” or “pf”, among others.

Their findings challenge long-held notions that human anatomy for the diversity of speech sounds was established with the emergence of Homo sapiens about 300,000 years ago and sounds in languages have remained unchanged for at least 10,000 years.

“We now have a strong case to think that sounds like the labiodentals are surprisingly recent in human history,” Damian Blasi, a linguistics researcher at the University of Zurich who led the study, told The Telegraph.

The research study by Blasi and his collaborators from France, Germany, the Netherlands and Russia will appear in the US journal Science on Friday.

The new research has indicated that the use of labiodental sounds — which are produced by touching the lower lip to the upper teeth — increased dramatically only over the past 3,000 to 6,000 years in parallel with the rise of food processing, milling and softer food.

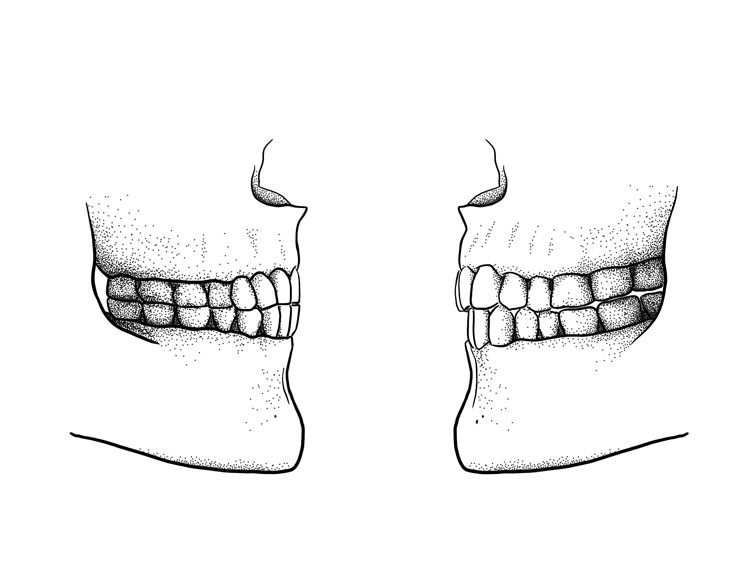

Humans are born with a bite configuration that is called overbite and overjet and favours labiodental sounds. But continuous and substantial tooth wear resulting from chewing on food changes the teeth configuration to an edge-to-edge bite.

However, the study has shown that a shift in adult tooth configuration that keeps the upper teeth slightly more in front as compared to the lower teeth correlates with the emergence of milling of cereals and softer food.

“Before access to softer diets through food processing, the bite would naturally develop into an edge-to-edge bite with age,” said Steven Moran, a linguist and co-author at Zurich. “It takes a lot more effort to produce labiodental sounds such as f or v with the teeth in the edge-to-edge position.”

American linguist Charles Hockett had in 1985 first proposed that labiodentals are overwhelmingly absent in languages whose speakers live from hunting and gathering, because the associated wear and tear diet induces an edge-to-edge bite.

The study found that only 49 per cent of the world’s languages contain labiodental sounds. And, just as Hockett had predicted, hunter-gatherer societies had fewer labiodentals.

The study found that, on average, hunter-gatherer societies — with less access to processed and softer food — have only 27 per cent the number of labiodentals observed in societies with abundant access to processed food.

The researchers said their analysis of a database of Indo-European languages suggests that the labiodental sounds emerged between 3,000 and 6,000 years ago. Still, multiple languages worldwide lack labiodentals altogether.

“In India, for instance, Assamese and Awadhi, according to our database, lack labiodentals,” Blasi said. “A variety of Spanish called Rioplatense Spanish does not feature a ‘v’. It may be that languages with a long tradition of access to soft diets do not develop them at all, as in the case of Japanese which has no labiodentals whatsoever.”