Google said it has achieved a breakthrough in quantum computing research, saying an experimental quantum processor has completed a calculation in just a few minutes that would take a traditional supercomputer thousands of years.

The findings, published on Wednesday in the scientific journal Nature, show that 'quantum speedup is achievable in a real-world system and is not precluded by any hidden physical laws,' the researchers wrote.

Quantum computing is a nascent and somewhat bewildering technology for vastly sped-up information processing. Quantum computers might one day revolutionise tasks that would take existing computers years, including the hunt for new drugs and optimising city and transportation planning.

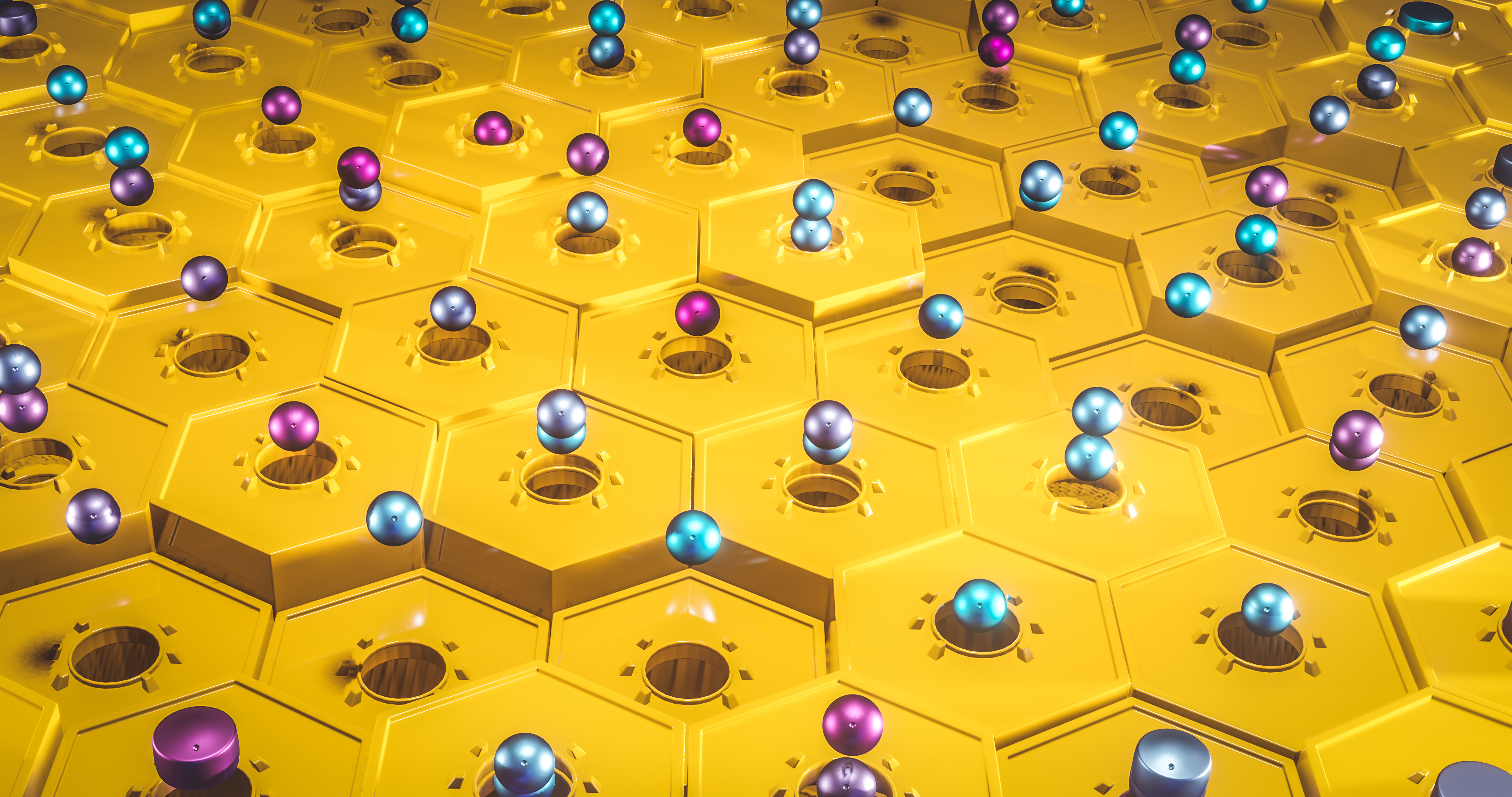

The technique relies on quantum bits, or qubits, which can register data values of zero and one — the language of modern computing — simultaneously. Big tech companies including Google, Microsoft, IBM and Intel are avidly pursuing the technology.

'Quantum things can be in multiple places at the same time,' said Chris Monroe, a University of Maryland physicist who is also the founder of quantum startup IonQ. 'The rules are very simple, they're just confounding.'

What's a quantum computer?

Describing the inner workings of a quantum computer isn’t easy, even for top scholars. That’s because the machines process information at the scale of elementary particles such as electrons and photons, where different laws of physics apply.

“It’s never going to be intuitive,” said Seth Lloyd, a mechanical engineering professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “At this microscopic level, things are weird. An electron can be here and there at the same time, at two places at once.”

Conventional computers process information as a stream of bits, each of which can be either a zero or a one in the binary language of computing. But quantum bits, known as qubits, can register zero and one simultaneously.

What can it do?

In theory, the special properties of qubits would allow a quantum computer to perform calculations at far higher speeds than current supercomputers. That makes them good tools for understanding what’s happening in the realms of chemistry, material science or particle physics.

That speed could aid in discovering new drugs, optimizing financial portfolios and finding better transportation routes or supply chains. It could also advance another fast-growing field, artificial intelligence, by accelerating a computer’s ability to find patterns in large troves of images and other data.

Where can you find one?

While quantum computers don’t really exist yet in a useful form, you can find some loudly chugging prototypes in a windowless lab about 40 miles north of New York City.

Qubits made from superconducting materials sit in colder-than-outer-space refrigerators at IBM’s Thomas J. Watson Research Center. Take off the cylindrical casing from one of the machines and the inside looks like a chandelier of hanging gold cables — all of it designed to keep 20 fragile qubits in an isolated quantum state.

“You need to keep it very cold to make sure the quantum bits only entangle with each other the way you program it, and not with the rest of the universe,” said Scott Crowder, IBM’s vice president of quantum computing.

Google's findings, however, are already facing pushback from other industry researchers. A version of Google's paper leaked online last month and researchers caught a glimpse before it was taken down.

IBM quickly took issue with Google's claim that it had achieved 'quantum supremacy,' a term that refers to a point when a quantum computer can perform a calculation that a traditional computer can't complete within its lifetime. Google's leaked paper showed that its quantum processor, Sycamore, finished a calculation in three minutes and 20 seconds — and that it would take the world's fastest supercomputer 10,000 years to do the same thing.

But IBM researchers say that Google underestimated the conventional supercomputer, called Summit, and said it could actually do the calculation in 2.5 days. Summit was developed by IBM and is located at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee.

Google has not commented on IBM's claims.

Whether or not Google has achieved 'quantum supremacy' or not may matter to competitors, but the semantics could be less important for the field of quantum research. What it does seem to indicate is that the field is maturing.

'The quantum supremacy milestone allegedly achieved by Google is a pivotal step in the quest for practical quantum computers,' John Preskill, a Caltech professor who originally coined the 'quantum supremacy' term, wrote in a column after the paper was leaked.

It means quantum computing research can enter a new stage, he wrote, though a significant effect on society 'may still be decades away.'

The calculation employed by Google has little practical use, Preskill wrote, other than to test how well the processor works. Monroe echoed that concern.

'The more interesting milestone will be a useful application,' he said.___O'Brien reported from Providence, Rhode Island.