Researchers have long argued that regions deep in Earth’s oceans may harbour sites from which all terrestrial life sprung. In the Atlantic, they gave the name “Lost City” to a jagged landscape of eerie spires under which they proposed that the life-preceding chemistry may have churned. Now, for the first time, specialists have succeeded in getting a glimpse of this potential Garden of Eden.

A recent report in the journal Science tells of a 30-person team drilling deep into a region of the mid-Atlantic seabed and pulling up nearly a mile of extremely rare rocky material. Never before has a sample so massive and from such a great depth come to light. The material is central to a major theory on the origin of life.

“We now have a treasure trove of rocks that will let us study the processes relevant to the emergence of life on the planet,” said Frieder Klein, an expedition team member at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution on Cape Cod in Massachusetts in the US.

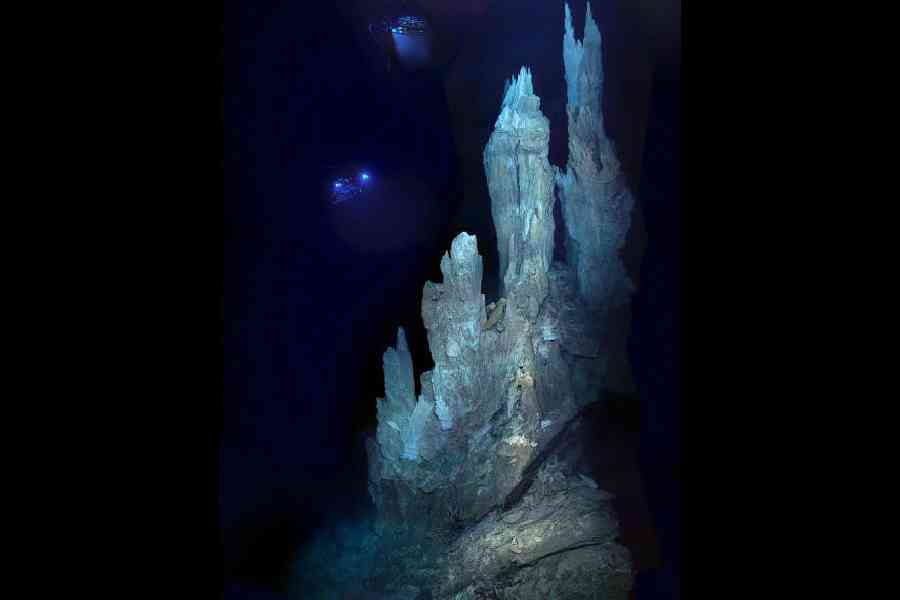

The drilled region sits alongside one of the volcanic rifts that crisscross the global seabed like the seams of a baseball. Known as mid-ocean ridges, the abyssal sites feature hot springs whose shimmering waters shed minerals into the icy seawater, building up strange mounds and spires that host riots of bizarre creatures.

For decades, scientists have theorised that the hot springs or their underlying rocks nurtured geochemical reactions that billions of years ago begot terrestrial life. Recently, they’ve accelerated their hunt for supporting clues.

“A lot of people did lab work and paper studies and modelling on the origin of life,” said Deborah Kelley, an oceanographer at the University of Washington, US, who has scrutinised such clues but is independent of the team. The new research, she said, “is really important”.

Early last year, the expedition drilled deep into the rocky seabed adjacent to one of the largest springs — a mid-Atlantic site some 1,400 miles east of Bermuda known as Lost City, which Kelley helped uncover in 2000. Its tallest spire rivals a 20-story building.

The core retrieved has a length of 1,268 metres, far deeper and more substantial than any comparable sample.

The operation has brought into scientists’ labs the first long section of rocks originating in the mantle — the inner layers between Earth’s crust and the planetary core. It is the largest region of the planet, but its inaccessibility makes it poorly understood. Over aeons, hot mantle rocks flow like extraordinarily thick fluids that slowly rearrange the cool planetary crust, lifting mountains, moving continents and causing earthquakes.

Scientists expect years of scientific discovery to emerge from detailed analyses of the rocky bonanza, including how it bears on the origin-of-life question.

The mantle breakthrough was part of the International Ocean Discovery Program, a research consortium of more than 20 countries using a giant ship to drill into the ocean floor and retrieve rocky samples that bare Earth’s secrets. The ship is a modified oil exploration platform, 470 feet long and with a 200-foot derrick, that lowers a hollow drill that bores into the seabed and retrieves cylindrical samples of rocks.

Lost City, like all deep springs, formed when water moving beneath the seabed gained enough heat to rise buoyantly and mix with icy seawater, prompting the precipitation of minerals that created its spires and towers.

Its discovery, however, marked the scientific debut of a new class of deep spring very different from those previously studied, in which rock chimneys spew extraordinarily hot water black with minerals. In contrast, Lost City was located not atop the mid-Atlantic rift but off to one side, its fluids cooler and spires taller.

The discovery raised waves of excitement in the community that studies life precursors because Michael J. Russell, a geochemist at Nasa’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, US, had predicted the existence of such cooler springs. He saw them as ideal for nurturing life.

NYTNS