Until recently, scientists believed modern humans left Africa in one enormous exodus about 65,000 years ago. But a new climate model suggests that modern humans had several windows of opportunity to leave the continent far earlier.

The study, published in Nature Communications, reconstructs the climate of northeastern Africa over 3,00,000 years. The scientists identified when there would have been enough rainfall to allow a hunter-gatherers’ group to survive the journey to the Arabian Peninsula.

Archaeological and genetic data still support the idea that all non-African people descended from a single migration that left the continent between 50,000 and 80,000 years ago. But the new paper bolsters the theory that Homo sapiens had multiple migrations out of Africa.

Even if various groups succeeded in leaving the continent, they may not each have played a large role in populating the world. An earlier constellation of fossils, some with contested dating, highlights some of H. sapiens’ false starts: part of a middle finger from 85,000 years ago, found in Arabia; a human jawbone from at least 1,77,000 years ago, found in Israel; a skull from possibly 2,10,000 years ago, found in Greece.

It is inviting to extrapolate the timing and paths of these early journeys from these archaeological records. But the fossils offer “limited, rather gappy lines of evidence” of possible migrations, said Andrea Manica, an evolutionary ecologist at the University of Cambridge, UK, and an author of the new paper. Manica believes an ecological model could tackle the question from a new angle: first predict what would have been possible, then see if the fossils line up.

“It’s an intriguing question to ask whether there were environmental thresholds for those earlier dispersals, even though those dispersals may have been limited or short-lived,” said Rick Potts, a paleoanthropologist who directs the Human Origins Program at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, US.

“The new paper grasps the important thing,” said Potts, who was not involved with the research. “There were multiple instances of our species’ dispersal beyond Africa prior to the main one.”

Manica and Robert Beyer, a researcher at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany, first devised their ecological approach in 2018. Scientists had already modelled the climate as far back as 1,25,000 years, but Manica and Beyer wanted to go back to the date of the earliest anatomically modern human fossils, which were found in Morocco and are estimated to be at least 3,00,000 years old.

To predict when Homo sapiens feasibly could have moved through northeastern Africa and the Arabian Peninsula, the researchers needed to find out the absolute minimal conditions in which humans could survive. “We wanted to build up this catalogue of the good times and bad times,” Manica said.

They looked at distribution maps of present-day hunter-gatherers and found that human populations are generally not recorded in areas where precipitation falls below 3.5 inches per year. Rainfall this trifling is not enough to sustain patches of reeds, grasses and shrubs that feed the grazing animals that early humans may have depended on.

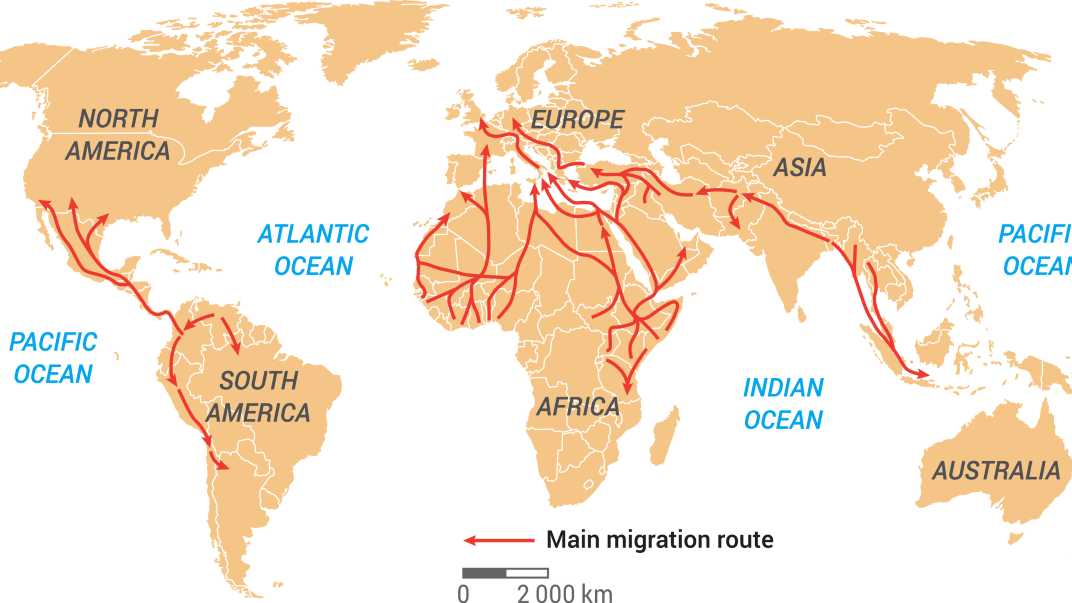

Once the researchers set the threshold of survivability at 3.5 inches, they overlaid their climate reconstructions to see when conditions might have been sweet enough to travel through two possible routes into Eurasia: the Sinai Peninsula up north and, further south, the Strait of Bab-el-Mandeb, which separates the Horn of Africa from contemporary Yemen.

Their model revealed a handful of historical windows during which there was enough rainfall and relatively low sea levels to sustain a human migration out of Africa. The Sinai land bridge was crossable several times, as early as 2,46,000 years ago, and the southern strait had even more favourable windows, including the period 65,000 years ago.

The sheer number of crossing opportunities surprised Manica, given the robust evidence suggesting that only the recent mass exodus had peopled the world with Homo sapiens. So the question still stands: If some Homo sapiens were able to colonise Eurasia far earlier, why were they not successful?

The researchers have some theories. If early humans could have moved out of Africa much earlier, they would have faced stiff competition from other early human species; the north was a Neanderthal stronghold, and much of East Asia was probably populated by another extinct human lineage, the Denisovans. The models also suggest that dry periods often followed the favourable windows, which could have isolated any populations undertaking an exodus. But the authors also note that even if times were good and wet, humans may not have taken advantage of these periods to migrate out.

Abdullah Alsharekh, an archaeologist at King Saud University in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, who was not involved with the research, said he appreciated the paper’s examination of the prehistoric Arabian climate. “The last couple of decades have shown that many of our questions about out-of-Africa models can be greatly enhanced by more on-the-ground research in Arabia,” Alsharekh wrote in an email. “What lies beneath those sandy deserts?”

Manica has a similar hope: that future archaeological excavations and genetic investigations will shed more light on Homo sapiens’ staggered foray out of Africa — both the earlier, seemingly unsuccessful waves and the main migration that unleashed Homo sapiens to irrevocably alter the rest of the world.

NYTNS