At sunset on a late summer weekend in 1924, crowds flocked to curbside telescopes to behold the advanced alien civilisation they believed to be present on the surface of Mars.

“See the wonders of Mars!” an uptown sidewalk astronomer shouted in New York City on August 23. “Now is your chance to view the snowcaps and the great canals that are causing so much talk among the scientists. You’ll never have such a chance again in your lifetime.”

That weekend, Earth and Mars were separated by just 34 million miles, closer than at any other point in a century. Although this orbital alignment, called an opposition, occurs every 26 months, this one was particularly captivating to audiences across continents and inspired some of the first large-scale efforts to detect alien life.

“In scores of observatories, watchers and photographers are centering their attention on that enigmatic red disk,” journalist Silas Bent wrote on August 17, 1924.

Scientists plotted for years to make the most of the Martian “close-up”. To aid the experiments, the US Navy cleared the airwaves, imposing a nationwide period of radio silence for five minutes at the top of each hour from August 21 to 24 so that messages from Martians could be heard. A military cryptographer was on hand to “translate any peculiar messages that might come by radio from Mars”.

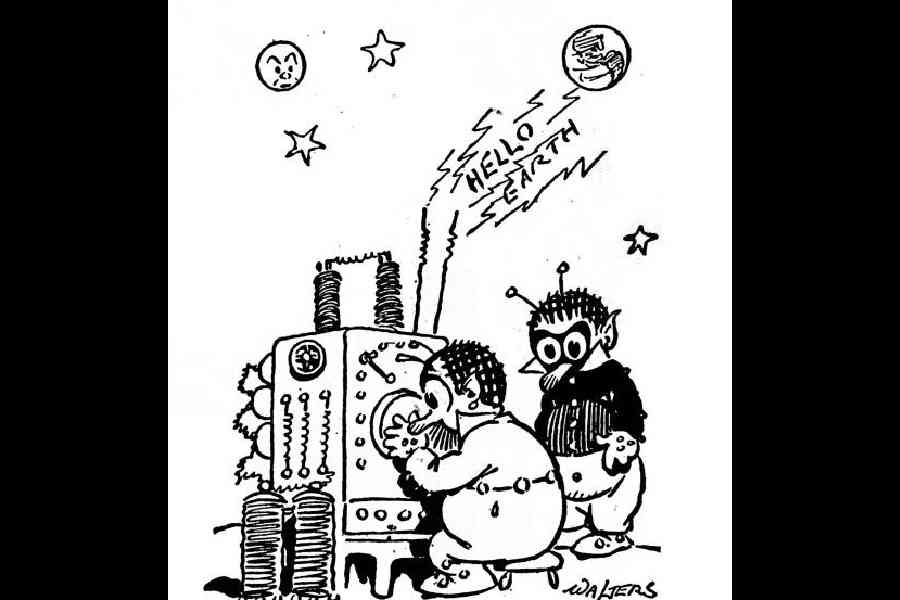

Then, lo and behold, an astonishing radio signal arrived with the opposition.

A series of dots and dashes, captured by an airborne antenna, produced a photographic record of “a crudely drawn face”, according to news reports. The tantalising results and subsequent media frenzy inflamed the public’s imagination. It seemed as if Mars was speaking, but what was it trying to say?

A century has elapsed since the Mars mania of 1924, but the source of that strange signal remains a mystery. The original paper record is presumed lost, though digital copies have survived, ensuring that the crudely drawn face continues to stare out at us across time.

But the story of the 1924 Mars opposition is as much about the audacity of attempting a detection of extraterrestrial life as it was about the murky outcomes. Some things have changed, such as our technologies for studying the cosmos. But what endures is that sneaky feeling that we are not alone in the universe.

“We need some cosmic company out there, whether it’s in the form of gods or extraterrestrials,” said Steven Dick, an astronomer and former Nasa chief historian who has written about humanity’s interest in aliens. “That’s a nice thought, but it’s not science,” he added.

In the expansive collections of the Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation near Detroit, there is a boxy artifact that was designed for the trenches and battlefields of World War I. In August 1924, it wound up serving as an interplanetary communications prototype.

Kristen Gallerneaux, a sonic historian and a curator of communication and information technology at the Henry Ford, is a caretaker of many technological relics. But they have a special fondness for the device, a Navy-type model SE 950 radio, and its historic role as a would-be alien-detector.

Manufactured on March 26, 1918, by the National Electrical Supply Co., the hardy portable radio was designed to support troops in combat, but this unit was never battle tested. It ended up, instead, in the Washington laboratory of Charles Francis Jenkins, an inventor who played a key role in the development of television.

It might have been used in many postwar experiments, but its golden hour arrived before the 1924 Mars opposition when astronomer David Peck Todd enlisted Jenkins to solve a problem that still animates the community involved in the search for extraterrestrial intelligence: if messages from intelligent aliens are wafting through space, how might we capture them?

The astronomer and the inventor cobbled together an answer. During the opposition, a dirigible was launched from the US Naval Observatory in Washington to an altitude of just under two miles. It carried an antenna, pointed at Mars, that relayed signals back from its aerial position to the SE 950 radio in Jenkins’ lab.

The data was then fed into the inventor’s “Radio Camera”, which converted radio signals into optical flashes that left imprints on a 38-foot-long roll of photographic paper. It was this process that produced the repeating pattern that many viewers interpreted as a face.

As some people longed for interplanetary validation, others worried about the wisdom of communicating with alien neighbours. A 1919 editorial titled “Let the Stars Alone” suggested that humans could be “unprepared” for “superior intelligences”.

The opposition was an opportunity to road-test these competing ideas. From a hilltop in England, a group recorded “strange noises” that “could not be identified as coming from any earthly station”. In Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, a signal “led radio experts here seriously to consider the theory that Mars is trying to ‘tune in’”.

Ultimately, the opposition produced no lasting evidence of Martian life, a result that vindicated scientific skeptics who had spent years pointing to the Red Planet’s absence of water or breathable air. Such truth seekers were often mocked.

“Some great talkers conclude that Mars must be uninhabitable,” French astronomer Camille Flammarion, a firm believer in intelligent Martians, wrote in March 1924. “This is not the reasoning of philosophers, but of fish,” he continued, comparing skeptics to fish who believe life out of water is impossible.

Regardless of the source, the radio signals and Mars fever of August 1924 helped set the stage for more practical and scientific efforts to search for aliens.

NYTNS