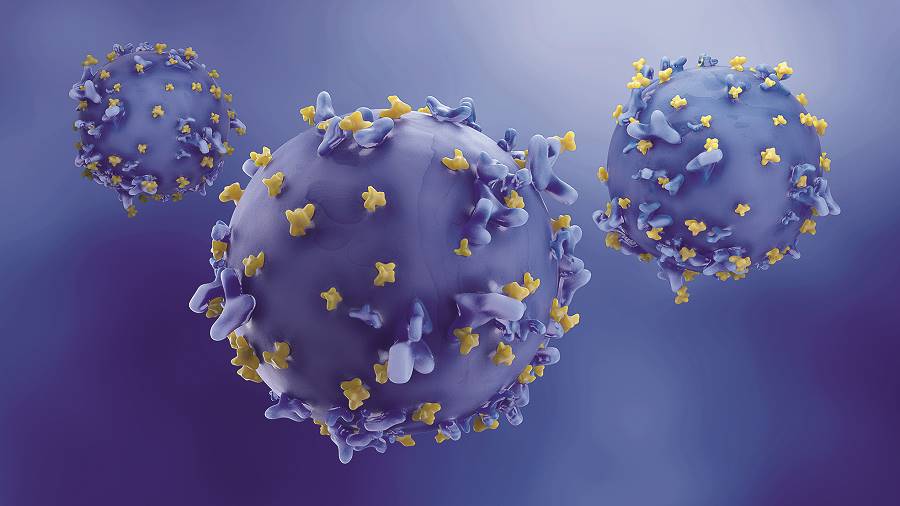

Eight months ago, the new coronavirus was unknown. But to some of our immune cells, the virus was already something of a familiar foe.

A flurry of recent studies has revealed that a large proportion of the population — 20 to 50 per cent in some places — might harbour immunity soldiers called T cells that recognise the new virus despite having never encountered it before.

These T cells, which lurked in the bloodstreams of people long before the pandemic began, are most likely stragglers from past scuffles with other, related coronaviruses, including four that frequently cause common colds. It’s a case of family resemblance: in the eyes of the immune system, germs with common roots can look alike.

The presence of these T cells has intrigued experts, who said it was too soon to tell whether the cells would play a helpful, harmful or entirely negligible role in the world’s fight against the new coronavirus. But should these so-called cross-reactive T cells exert even a modest influence on the body’s immune response to the new coronavirus, they might make the disease milder — and perhaps partly explain why some people who catch the germ become very sick, while others are dealt only a glancing blow.

“If you have a population of T cells that are armed and ready to protect you, you could control the infection better than someone who doesn’t have those cross-reactive cells,” said Marion Pepper, an immunologist at the University of Washington, US, who is studying the immune responses of Covid-19 patients. “That’s what we’re all hoping for.”

T cells are an exceptionally picky bunch. Each spends the entirety of its life waiting for a very specific trigger, such as a hunk of a dangerous virus. Once that switch is flipped, the T cell will clone itself into an army of specialised soldiers, all with their sights set on the same target. Some T cells are microscopic assassins, tailor-made to home in on and destroy infected cells; others coax immune cells called B cells into producing virus-attacking antibodies.

The first time a virus infects the body, this response is sluggish; it takes several days for the immune system to sort out which T cells are best suited for the job at hand. But subsequent encounters typically prompt a response that is stronger and faster, thanks to a reserve force of T cells called memory T cells, that lingers after the initial threat has passed and can quickly be called into action again.

Usually, this process operates best when T cells must battle the same pathogen again and again. But these recruits are more flexible than they are often given credit for, said Laura Su, an immunologist and T cell expert at the University of Pennsylvania, US. Should these cells chance upon something that bears a strong resemblance to their germ of choice, they can still be roused to fight, even if the invader is a total newcomer.

In theory, cross-reactive T cells can “protect almost like a vaccine”, said Smita Iyer, an immunologist at the University of California, Davis, US, who is studying immune responses to the new coronavirus in primates. Previous studies have shown that cross-reactive T cells may guard people against different strains of the flu virus, and perhaps confer a trace of immunity against dengue and Zika viruses, which share a family tree.

The case for coronaviruses is less clear cut, said Alessandro Sette, an immunologist at the La Jolla Institute for Immunology, California, US, who has led several studies examining cross-reactive T cells to the new coronavirus.

Researchers have found people in the US, Germany, the Netherlands, Singapore and the UK who have never been exposed to the new coronavirus but who carry T cells that react to it in the lab.

Researchers are eager to understand the history of these T cells, because that might help reveal who is more likely to have them. A growing body of evidence, including data published recently in Science by Sette and his colleagues, points to common-cold coronaviruses as a potential source. But even unrelated viruses can share similar features, and researchers may never know for sure what originally “drove their development”, said Avery August, an immunologist and T cell expert at Cornell University, US.

Whatever the origin of T cells, their mere existence could be encouraging news. There is much more to the immune system than T cells, but even a semblance of pre-existing immunity could mean that people who have recently grappled with the common cold may have an easier time fighting off a nastier member of the coronavirus clan.

Cross-reactive T cells alone probably would not be enough to completely stave off infection or disease. But they might alleviate symptoms of the coronavirus in people who happen to carry these cells, or extend the protection provided by a vaccine. “That would be awesome,” Iyer said.

But cross-reactive T cells are not necessarily a benevolent force. They could instead be ineffectual souvenirs of infections past, with “absolutely no relevance” to how well people fare against the new coronavirus, Sette said. There is even a small chance that pre-existing T cells could raise the risk for serious symptoms of Covid-19, although experts consider this possibility unlikely. T cells that are primed to recognise common-cold coronaviruses might marshal only a lacklustre response to the current coronavirus, potentially sapping resources from other populations of immune cells that have a better shot at defeating the new invader.

T cells are also expert orchestrators. Depending on the signals they send out, they can synchronise cells and molecules from disparate parts of the immune system into a tag-teamed attack, or quell these assaults to return the body to baseline.

If it turns out that cross-reactive T cells tend to quieten the response, they could suppress a person’s immune defence before it has a chance to kick into gear, August said.

Then again, many types of T cells exist, and all operate as part of a complex immune system. “It’s like some people are trying to say this is ‘good’ or ‘bad’,” Su said. “It’s probably more nuanced than that.”

New York Times News Service