A jumble of cords and two devices the size of soda cans protrude from Austin Beggin’s head when he undergoes testing with a team of researchers studying brain implants meant to restore function to those who are paralysed.

Despite the cumbersome equipment, it is also when Beggin feels most free. He was paralysed from the shoulders down after a diving accident eight years ago, and the brain device picks up the electrical surges his brain generates as he envisions moving his arm. It relays those signals to cuffs on the major nerves in his arm. They allow him to do things he had not done on his own since the accident, like lift a pretzel to his mouth.

“This is like the first time I’ve ever gotten the opportunity or I’ve ever been privileged and blessed enough to think, ‘When I want to open my hand, I open it,’” Beggin, 30, said.

The work at the Cleveland Functional Electrical Stimulation Center, US, represents some of the most cutting-edge research in the brain-computer interface field, connecting the brain to the arm to restore motion.

It’s a field that Elon Musk wants to advance, announcing in a recent presentation that brain implants from his company Neuralink would someday help restore sight to the blind or return people like Beggin to “full-body functionality”.

Researchers caution that the goal is much harder and more dangerous than it may seem. And they warn that Musk’s goals may never be possible — if they are even worth doing in the first place.

“It is fun to think about science fiction scenarios describing how the world might be,” said Paul Nuyujukian, a professor of bioengineering and neurosurgery at Stanford University, US. “But given where we are right now with the science, it is not clear how those scenarios will be realised.”

The scientists at the Neuralink event agreed that the engineering Musk showed off was an elegant mashup of some of the best ideas in the decades-old field. Replacing the sodacan-like protrusion from the head would indeed be a significant advance, they acknowledged.

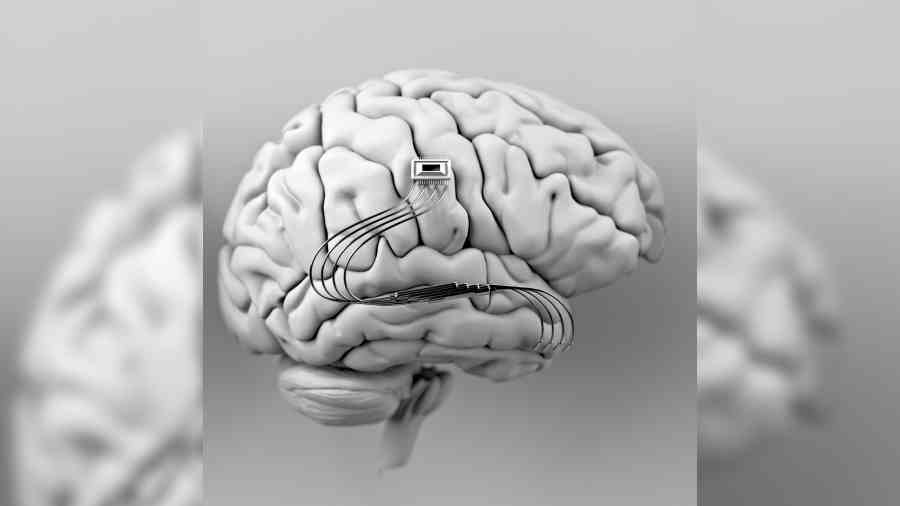

Neuralink’s device prototype would eliminate that problem, but only after patients undergo robotic surgery to cut a hole in the head slightly larger than a quarter. Then the robot knits 1,024 cobweb-thin electrode tendrils into the grey matter of the brain and rests the pucklike device in the hole.

With work so delicate, some researchers in the field worry that one high-profile misstep could erase years of progress.

“The communications coming out of Neuralink too often sounds like cowboy activity, right?” said Marcus Gerhardt, chief executive of Blackrock Microsystems, a brain-computer interface company that could be a Musk rival.

Beggin is one of about three dozen people who have a device called a “Utah array” implanted in the brain for research purposes. The device includes a small grid of electrodes dipped barely 2 millimetres into his brain. That is linked to a portal mounted on his head and, via cables, to another computer.

Most of the days that Beggin spends working with the team involve looking at a moving arm or hand on a computer screen and envisioning himself making the same motion. That allows researchers to detect the neuron-firing patterns in his brain that give rise to each movement. Those signals are communicated to a system that manipulates eight nerves in his arm to make it move, said A. Bolu Ajiboye, a professor of biomedical engineering at Case Western Reserve University whose team has been working with patients like Beggin.

Scientists are working to map the brain’s visual centre so points of light can be projected in the mind’s eye to help the blind see shapes and letters NYTNS

The work can be tedious, Beggin said, but he finds it worthwhile for the days when he can move his hand. His experience builds on work with a prior volunteer, who was also paralysed in the arms and legs, and managed to lift a forkful of mashed potatoes to his mouth with the system.

Scientists are working to map the visual centre of the brain so points of light can be projected in the mind’s eye to help the blind see shapes and letters. Other teams are working on translating neural electricity into speech, cursor control, handwriting and typing applications. Several companies, including Neuralink, are working on fully implantable devices. Paradromics, a start-up in Austin, Texas, US, is developing a device that sits inside the skull. Synchron, based in New York City, is taking a different approach, making an incision in the chest and pushing a tube-shaped device into an artery close to the brain. This avoids the dangers of brain surgery, but the signal it captures from the brain is considerably weaker.

Despite all the promise, scientists say this technology has very little to offer to the typical consumer, as it is merely approaching the speed and precision of able-bodied control.

During the Neuralink presentation, a video showed a monkey named Pager reportedly using a prototype implant in its brain to move a cursor across a computer screen. Musk announced that Neuralink was seeking permission from the Food and Drug Administration to test the device in humans.

This would be a notable step forward. Others have tested wireless devices in humans, but Neuralink has built a chip smaller, faster and potentially more powerful than anything that has come before.

“They basically sourced a lot of the best ideas out there in the top of the field and paid to bring them together into a new system,” said Cristin Welle, a University of Colorado neuroscientist and former FDA brain-implant lab director and device consultant. “And I think that is exciting.”

NYTNS