Once, in another lifetime, I witnessed an atomic explosion. This was in the 1960s at the Nevada Test Site, about an hour northwest of Las Vegas where the US military tested bombs. I was working for EG&G, a military contracting company that supplied all the instrumentation for the test site. My job, to study the effects of nuclear explosions on the atmosphere, was sufficient to keep me out of the Vietnam War draft. Cabriolet, as the test was called, contained the force of 2,300 tons of TNT.

Twice a year, on the first Saturdays of April and October, the US Army opens the gate to the White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico, allowing in civilians to tour a patch of sand known as the Trinity Site, where the very first atomic explosion was set off and the history of nuclear dread began. It was so named by J. Robert Oppenheimer, the physicist who led the Manhattan Project to build the bomb, inspired by lines like these in the poems of John Donne. Batter my heart, three-person’d God, for you/As yet but knock, breathe, shine, and seek to mend;/That I may rise and stand, o’erthrow me, and bend/Your force to break, blow, burn, and make me new.

According to the Trinity website, the Stallion Gate would open promptly at 8am; when we arrived not long after the crack of dawn, a 4-mile-long caravan of cars was ahead of us. The idea to visit came from Michael Turner, an old friend and cosmologist recently retired from the University of Chicago, US, and now with the Kavli Foundation in Los Angeles. He brought along an old pal from his undergraduate days at the California Institute of Technology, Robert J. Miller, who had helped invent the computer touch pad.

We continued through a gate and down a path lined with barbed wire, Keep Out signs and warnings about rattlesnakes, to a fenced-in area littered with glassy gravel, sand and tufts of sagebrush and sparse grass. It was here at 5:29:45am on July 16, 1945, that arguably the most consequential physics experiment of the 20th century took place.

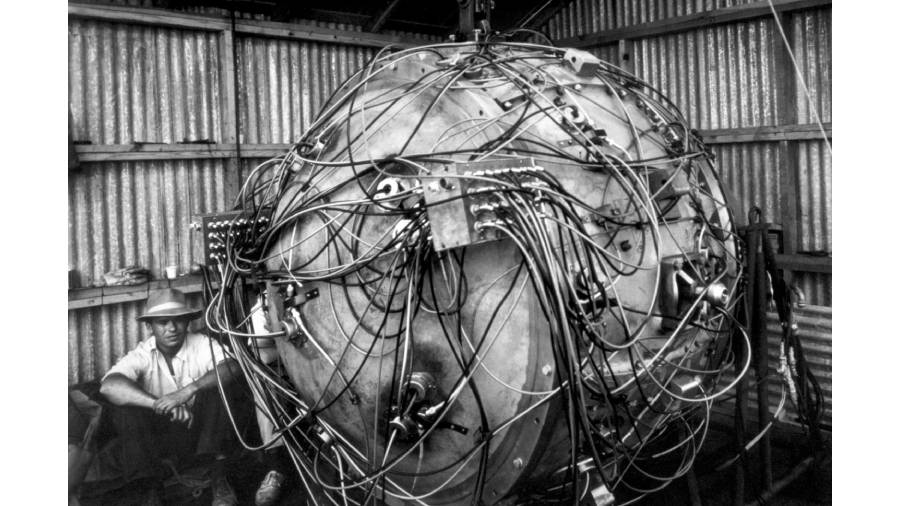

The bomb would use explosives to squeeze a softball-size lump of plutonium to critical density, ideally resulting in a soul-rattling explosion. It worked, lighting up the New Mexico landscape a few minutes before dawn and causing Oppenheimer to mutter to himself a verse from the Bhagavad Gita: “Now I am become death, destroyer of worlds.”

Three weeks later, on August 6, 1945, a bomb of slightly different design was dropped on Hiroshima, Japan, killing an estimated 1,40,000 people. Fat Man, a plutonium bomb of the kind tested at Trinity, was used on Nagasaki on August 9, and the end of WWII soon followed.

The present-day remains of the “Jumbo” NYTNS

At Trinity’s ground zero, people were milling around as if at a county fair, but there was little to see. The detonation created a crater 8-ft deep, a half-mile wide and lined with glassy pebbles called trinitite: sand that had been swept up in the fireball, vaporised and then fell back down in molten radioactive droplets. But gradually the pebbles were shovelled out and the hole filled with scrubby sand, weeds and rocks. Now display stands sold snacks and souvenirs; at one table, docents were using a Geiger counter to show off mildly radioactive rocks.

The Gadget was detonated atop a 100-ft tower. All that remained was a stub of metal sticking out of the ground. An obelisk of black rocks, with a plaque commemorating the event, marked the exact point of ground zero.

The ground below our feet was littered with green shards of trinitite. They were allegedly radioactive, and signs warned that removing any stones constituted theft of government property and could lead to fines or even jail time. The signs seemed to remind visitors

to bend down and retie their shoelaces, perhaps to gather a promising souvenir or two of the original sin in the process.

There are now more than 13,000 nuclear warheads on Earth, according to a study by the Federation of American Scientists. Perhaps miraculously, not one has been detonated in anger since 1945, although stories keep emerging of close calls.

Recently it was revealed that when the Chinese Communists seemed to be threatening Taiwan in 1958, the US military drew up plans to bomb mainland China. Another near tragedy occurred on September 26, 1983, three weeks after Soviet fighters had shot down Korean Air Lines Flight 007.

Stanislav Petrov, a lieutenant colonel in the Soviet air defense forces, was in charge that day of a command centre called Oko, an early-warning system that relied on a network of satellites to detect attacks. The system reported that a half-dozen missiles had been launched from the US and were headed toward the Soviet Union.

Petrov’s task was to relay the warning to his superiors in Moscow, who were likely to order a retaliatory strike. But Petrov, an engineer, held back, worried that the signal might be a false alarm. Several tense minutes in the early-warning command centre passed by until finally ground-based radar confirmed that no missiles were incoming. The error was later traced to unusual reflections from high-altitude clouds.

Petrov was later reprimanded for insufficiently documenting his work on that day. To the rest of the world he was a hero. In 2006 he was invited to address the United Nations and tour the US, a trip that was documented in a film, The Man Who Saved the World.

NYTNS