More than three millenniums after Tutankhamen was buried in southern Egypt, and a century after his tomb was discovered, Egyptologists are still squabbling over whom the chamber was built for and what, if anything, lies beyond its walls.

At the centre of the rumpus is confrontational enthusiast Nicholas Reeves, 66, who shares a home near Oxford, UK, with a nameless house cat. In July 2015, Reeves, a former curator at the British Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, posited the tantalising theory that there were rooms hidden behind the northern and western walls in the treasure-packed burial vault of Tutankhamen, otherwise known as King Tut.

It was long presumed that the small burial chamber, constructed 3,300 years ago and known to specialists as KV62, was originally intended as a private tomb for Tutankhamen’s successor, Ay, until Tutankhamen died prematurely at 19. Reeves proposed that the tomb was, in fact, merely an antechamber to a grander sepulchre for Tutankhamen’s stepmother and predecessor, Nefertiti. What’s more, Reeves argued, behind the north wall was a corridor that might well lead to Nefertiti’s unexplored funerary apartments, and perhaps to Nefertiti herself.

The Egyptian government authorised radar surveys using ground-penetrating radar that could detect and scan cavities underground. At a news conference in Cairo in March 2016, Mamdouh Eldamaty, then Egypt’s antiquities minister, announced that there was an “approximately 90 per cent” chance that something — “another chamber, another tomb” — was waiting beyond KV62.

Yet two years and two separate radar surveys later, a new antiquities minister declared that there were neither blocked doorways nor hidden rooms inside the tomb.

Despite the setback, Reeves soldiered on. “Much of what Tutankhamen took to the grave had nothing to do with him,” said Reeves, who spoke by video from his home office. He maintained that King Tut had inherited a suite of lavish burial equipment that had then been repurposed to accompany him into the afterlife, including his famous gold death mask.

Reeves has conducted research directly in the tomb on several occasions over the years. He speculated that one doorway — in the west — opened into a Tutankhamenera storeroom and that another, which aligns with both sides of the entrance chamber, opened to a hallway continuing along the same axis in form and orientation reminiscent of a more extensive queen’s corridor tomb.

“I saw early on, from the face of the north wall subject, that the larger tomb could only belong to Nefertiti,” Reeves said. “I also suggested, based on evidence from elsewhere, that the perceived storage chamber to the west of the burial chamber might have been adapted into a funerary suite for other missing members of the Amarna royal family.”

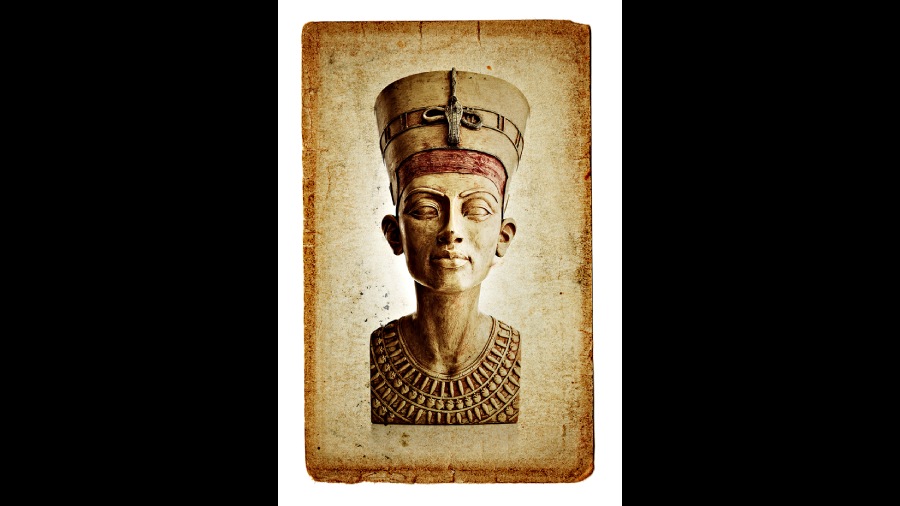

Queen Nefertiti

To support his radical reassessment, Reeves pointed to a pair of cartouches — ovals or oblongs enclosing a group of hieroglyphs — and a curious misspelling painted on the tomb’s north wall. The figure beneath the first cartouche is named as Tutankhamen’s Pharaonic successor, Ay, and is shown officiating at the young king’s burial carrying out the “opening the mouth” ceremony, a funerary ritual to restore the deceased’s senses — the ability to speak, touch, see, smell and hear. The key, Reeves said, is that both of the Ay cartouches show clear evidence of having been changed from their originals — the birth and throne names of Tutankhamen.

Reeves suggested that the cartouches had originally showed Tut burying his predecessor and that the cartouches — and hence the tomb — were put to new use.

“If you inspect the birth name cartouche closely, you see clear, underlying traces of a reed leaf,” he said in an email. “Not by chance, this hieroglyph is the first character of the divine component of Tutankhamen’s name, ‘-amun,’ in all standard writings.”

Beneath Ay’s throne name may be discerned a rare, variant writing of Tutankhamen’s throne name, “Nebkheperure”, employing three scarab beetles. This is a variant whose lazy adaptation provides the only feasible explanation for the strangely misspelt three-scarab version of the Ay throne name “Kheperkheperure” that now stands there, Reeves said.

He deduced that the scene had originally depicted not Ay presiding over the interment of Tutankhamen, but Tutankhamen presiding over the burial of Nefertiti. There are two visual clinchers, he said. The first is the “rounded, childlike, double underchin” of the Ay figure, a feature not present in any image currently recognisable as him, implying that the original painting of the king must have been of the chubby, young Tutankhamen. The second is the facial contours of the mummified recipient — until now presumed to be Tutankhamen — whose lips, narrow neck and distinctive nasal bridge are a “perfect match” for the profile of the painted limestone bust of Nefertiti on display in the Neues Museum in Berlin.

“There would have been no reason to include a depiction of this predecessor’s burial in Tutankhamen’s own tomb,” Reeves said. “In fact, the presence of this scene identifies Tutankhamen’s tomb as the burial place of that predecessor, and that it was within her outer chambers that the young king had, in extremis, been buried.”

At least part of the backlash against Reeves’ ideas can be traced to the politics of heritage. “Sure, some in Egypt take a different view from me, which is easy enough to understand,” Reeves said. “Archaeologists in the UK would, I am sure, look askance at some foreigner sounding off on who might be buried in Westminster Abbey. But my sole interest as an academic Egyptologist, my intellectual responsibility, is to seek out the evidence and report honestly and as objectively as possible on what I find.”

NYTNS