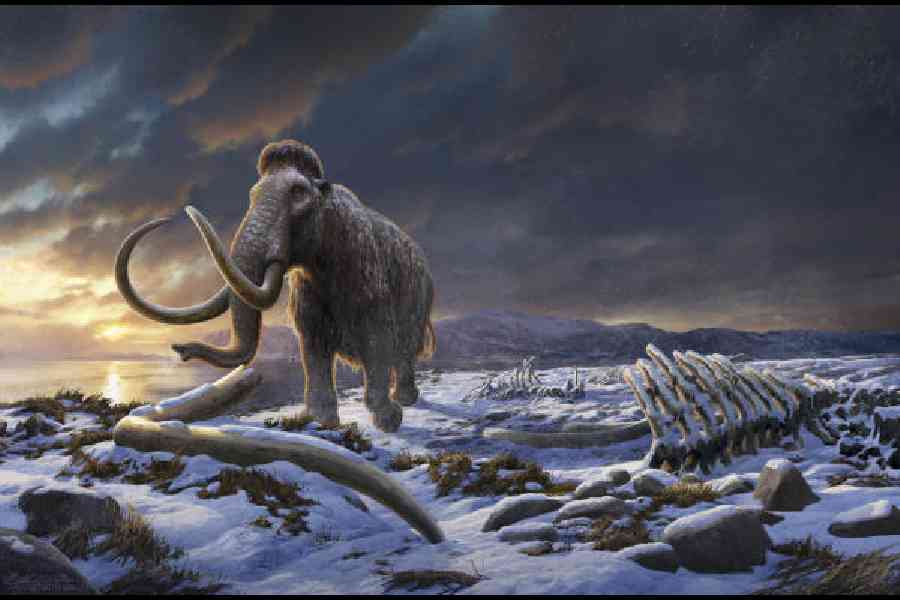

For millions of years, mammoths lumbered across Europe, Asia and North America. Starting roughly 15,000 years ago, the giant animals began to vanish from their vast range until they survived on only a few islands. Eventually they disappeared from those too, with one exception: Wrangel Island, a land mass the size of Delaware over 80 miles north of the coast of Siberia, Russia. There, mammoths held on for thousands of years — they were still alive when the Great Pyramids were built. When the Wrangel Island mammoths disappeared 4,000 years ago, mammoths became extinct for good.

For two decades, Love Dalén, a geneticist at Stockholm University in Sweden, and his colleagues have been extracting bits of DNA from fossils on Wrangel Island. In recent years, they have gathered entire mammoth genomes. Now, they have published a reconstruction of the genetic history of these enigmatic animals.

The scientists concluded that the island’s population was founded about 10,000 years ago by a tiny herd made up of fewer than 10 animals. The colony survived for 6,000 years, but the mammoths suffered from a host of genetic disorders.

Dalén and his colleagues examined the genomes of 14 mammoths that lived on Wrangel Island from 9,210 years to 4,333 years ago. The researchers compared this DNA with seven genomes from mammoths that lived on the Siberian mainland up to 12,158 years ago.

The genome of any animal contains a tremendous amount of information about the population it belonged to. In big populations, there is a lot of genetic diversity. As a result, an animal will inherit different versions of many of its genes. In a small population, animals will become inbred, inheriting identical copies of many genes.

The oldest Wrangel Island fossils contain identical versions of many genes. Dalén and his colleagues concluded that the island was founded by a remarkably tiny population of mammoths.

About 10,000 years ago, Wrangel Island was a mountainous region on the mainland of Siberia. Few mammoths spent time there, preferring lower regions where more abundant plants grew.

But at the end of the ice age, melting glaciers submerged the northern margin of Siberia. “There was one small herd of mammoths that happened to be on Wrangel Island when it was cut off from the mainland,” Dalén said.

The mammoths on the mainland faced significant challenges. Humans hunted them down, while the changing climate wiped out much of their grassland habitat, turning it to tundra.

But those stranded on Wrangel Island enjoyed a stroke of luck. The island was free of people and other predators, and they faced no competition from other grazing mammals. The climate on Wrangel Island turned it into an ecological time capsule, where the mammoths could still enjoy a diversity of ice-age plants.

“Wrangel Island was a golden place to live in,” Dalén said.

He and his colleagues found that the population on Wrangel Island expanded from fewer than 10 mammoths to about 200. That was probably the maximum number the island could support.

But life was far from perfect. The few animals that founded the Wrangel island population had very little genetic diversity. As a result, the mammoths probably suffered a high level of inherited diseases. Dalén suspects that these sick mammoths managed to survive for hundreds of generations only because they had no predators or competitors.

The new study doesn’t reveal how the mammoths met their end. There’s no evidence that humans are to blame; the earliest known visitors to Wrangel Island appear to have set up a summer hunting camp 400 years after the mammoths became extinct.

It’s possible that a tundra fire killed off the Wrangel mammoths, or the eruption of an Arctic volcano may have done them in. Dalén can even imagine that a migratory bird brought an influenza virus to Island, which then jumped to the mammoths and wiped them out.

“We’re left with a number of possible explanations, and we haven’t been able to narrow it down,” he said.

NYTNS