The Paris Climate Agreement brought together international governments including India, to combat climate change. As nations mobilise their resources in the quest to clean up their energy use, how is India doing? Supratim Das is a clean energy scientist with a PhD and MBA from Massachusetts Institute of Technology, US — he is also an IIT Delhi alumnus — currently working with a US-based green hydrogen startup, Electric Hydrogen, which manufactures next-generation electrolyzer plants that unlocks fossil-fuel parity green hydrogen at industrial scale.

What are your thoughts on the recent discovery of lithium in Kashmir and Rajasthan’s Degana?

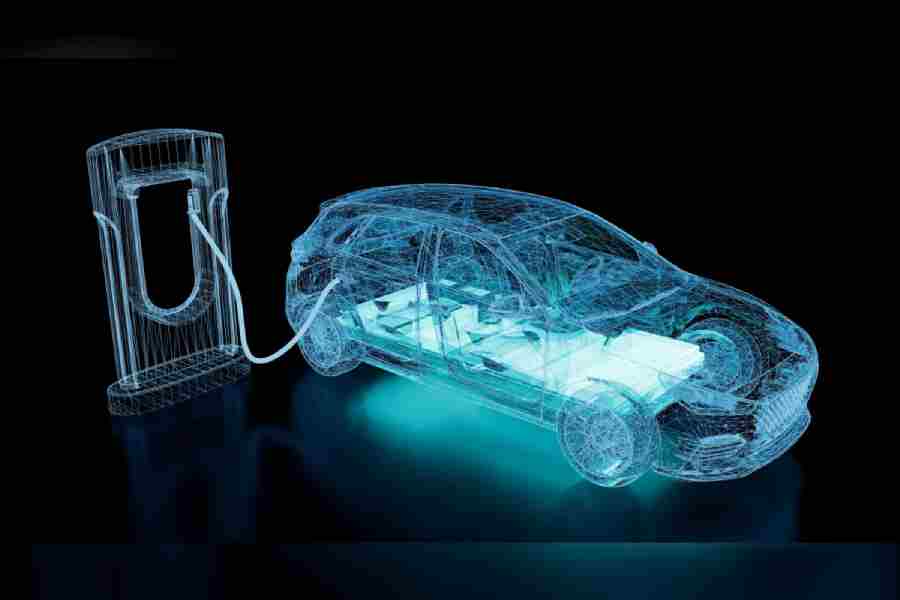

The discovery of a lithium reservoir in Kashmir could have significant implications for the economy and energy sector of the region and beyond. Lithium is a key component in the production of batteries used in electric vehicles (EVs) and energy storage systems, and its demand will increase as the world moves towards cleaner energy sources. If the lithium reservoir in Kashmir can be effectively extracted and processed, it could provide a significant boost to the local and national economies. The discovery in Rajasthan was just announced by the Geological Survey of India. It’s too early to comment on this.

How soon can we reap the benefits?

The permitting and commissioning of a new lithium mine takes 7-10 years, so the onus is on local authorities to expedite this. Another important factor is the cost of extraction of lithium, which remains unknown. One of the reasons why lithium of Chilean origin is so widely used is that its extraction cost is very low. Almost all lithium processing (that is, the chemical steps that convert the lithium salt that is mined into the form that is usable in a battery) is concentrated in China today. It will be interesting to see if India becomes a net exporter of lithium salts to China or establishes a domestic supply chain with in-house lithium processing and battery manufacture.

Is the lithium from Chile suitable for electric vehicles?

Yes. The lithium deposits in Chile are of high quality (lithium brines) and are generally considered to be among the best in the world in terms of purity and chemical composition. The lithium extracted from Chilean brines is used to produce lithium carbonate and lithium hydroxide. These are the two main chemicalcompounds used in the production of lithium-ion batteries, which are commonly used in EVs and other electronic gadgets.

MIT scientist Supratim Das

What are the most common uses of lithium batteries?

Common uses are in portable electronic devices due to their high energy density and long cycle life. In recent years, the use of lithium batteries has also become increasingly common in the automotive industry. Other common uses of lithium batteries include power tools, backup power systems, and in the grid to buffer the intermittency of renewable systems such as solar and wind power.

What exactly was your work in the field of renewable energy storage as a scientist?

I helped pioneer data-driven prediction of lithium-ion battery life using data from only a few cycles, using a combination of machine learning and lab experiments. I also created the world’s most powerful catalyst-free lithium-bromine flow battery, a potential ultimate solution for long-range EVs and grid-scale energy storage. I wrote two patents to reclaim precious materials and also destroy unwanted substances in an electrochemical system that uses electrodes, and splits water into hydrogen and oxygen using renewable energy.

What are the pros and cons of lithium as a source of renewable energy?

Lithium is not a source of renewable energy in itself, but it is a key component in many renewable energy technologies. Among the positives, they can store a lot of energy in a small volume and weight, making them ideal for portable devices and automobiles. They also have a long life cycle, are low-maintenance and require little to no upkeep. On challenges, lithium batteries are hazardous if damaged or overheated, which are mitigated by software intervention. Disposal and precious material (nickel, copper, cobalt) recycling is difficult at large volumes, the current industry being fragmented and in its infancy.

How do you see India’s future in clean energy?

India has set ambitious goals for its future in clean energy, driven by concerns over climate change and energy security. The country is the third-largest emitter of greenhouse gases, after China and the US, and has pledged to reduce its carbon emissions by 33-35 per cent from 2005 levels by 2030, as part of its commitment to the Paris Agreement.