Just keep telling the story,” says the director character in Wes Anderson’s film Asteroid City, which takes a stylised look at midcentury America’s fascination with space and interstellar communications. Later this year, the Lunar Codex — a vast multimedia archive telling a story of the world’s people through creative arts — will start heading for permanent installation on the moon aboard a series of unmanned rockets.

The Lunar Codex is a digitised collection of contemporary art, poetry, magazines, music, film, podcasts and books by 30,000 artists, writers, musicians and filmmakers in 157 countries. It’s the brainchild of Samuel Peralta, a physicist and an author in Canada.

Prints from war-torn Ukraine and poetry from countries threatened by climate change are in the Codex, as well as more than 130 issues of PoetsArtists magazine. Among the thousands of images are New American Gothic, by Ayana Ross, the winner of the 2021 Bennett Prize for female artists; Emerald Girl, a portrait in Lego bricks by Pauline Aubey; and the aptly titled New Moon, a 1980 serigraph by Alex Colville. Some works were commissioned for the project, including The Polaris Trilogy: Poems for the Moon, a collection of poetry from every continent, including Antarctica.

An art collector and poet himself, Peralta, the executive chair of the Toronto-based media and technology company Incandence, has been reaching out to creators through gallery and publishing connections to select the works for free inclusion in the Codex.

“This is the largest, most global project to launch cultural works into space,” Peralta said. “There isn’t anything like this anywhere.”

The Codex represents creators from a range of experiences. It includes several pieces from Connie Karleta Sales, an artist with the autoimmune disease neuromyelitis optica, who makes paintings using eye-gaze technology. Electric Joy, one of the works, “celebrates the colour and movement of my mind,” Sales said. “I might have limited use of my physical body, but my mind is limitless. It is dancing, laughing, crying and loving.”

Olesya Dzhurayeva, a Ukrainian printmaker, had evacuated Kyiv in April 2022 in the first months of the Russian attack when Peralta contacted her with a supportive message. He also asked for her permission to archive images of several of her linocuts in the Lunar Codex. “This project is so life-affirming with thoughts about the future,” she wrote. “Exactly what I needed in those first months.” A collection of her pieces are represented in the Codex, including a series of woodcuts printed with black Ukrainian soil.

The moon has hosted earthly art for decades. The Moon Museum, a tiny ceramic tile featuring line drawings by Forrest Myers, Andy Warhol, Claes Oldenburg, Robert Rauschenberg, David Novros and John Chamberlain, was discreetly attached to the leg of a lunar module left on the moon as part of the Apollo 12 mission in 1969. Fallen Astronaut, an aluminum sculpture by Belgian artist Paul van Hoeydonck, was left on the lunar surface by the Apollo 15 crew in 1971, with a plaque commemorating 14 astronauts who died in scientific service.

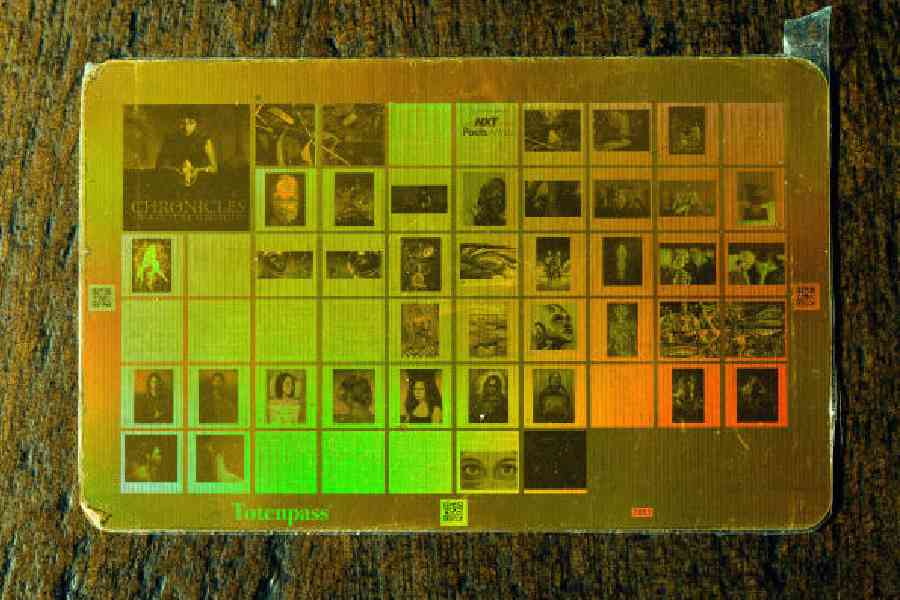

The Lunar Codex has bigger storytelling ambitions. It’s divided into four time capsules, with its material copied onto digital memory cards or inscribed into nickel-based NanoFiche, a lightweight analogue storage media that can hold 1,50,000 laser-etched microscopic pages of text or photos on one 8.5-by-11-inch sheet. The concept is “like the Golden Record,” Peralta said, referring to Nasa’s own cultural time capsule of audio and images stored on a metal disc and sent aboard the Voyager probes in 1977. “Gold would be incredibly heavy. Nickel wafers are much, much lighter.”

Peralta, a polymath, is the son of Filipino anthropologist/playwright Jesus T. Peralta and abstract artist Rosario Bitanga-Peralta. He started the Lunar Codex during the pandemic to send his own work, including his science fiction books, to the moon before deciding to expand the scope.

Peralta sees the Lunar Codex as “a message in the bottle for the future that during this time of war, pandemic and economic upheaval people still found time to create beauty.”

NYTNS