Ritwik Ghatak enters his 100th year on Monday. Many consider him one of the greatest filmmakers of the world. At home in Bengal, Neeta’s heartrending cry in his film Meghe Dhaka Tara, “Dada ami banchte chai (Dada, I want to live)” — the sudden, fierce expression of her desire for life that seems to be echoed frantically by the mountains around her — is so familiar that it would have become a cliché by now but for its ability to shake us to the core every time.

Hardly acknowledged in his lifetime, Ghatak is an icon now, his gaunt face everywhere. His name is forever embedded in the binary that refuses to go away: “Ray or Ghatak?” His legacy remains powerful and various, and sometimes not obvious in popular consciousness, as it happens with the greatest of influences. On this occasion, it is worth looking at again.

Ghatak changed the narrative of Indian cinema, literally. As Sanjoy Mukhopadhyay, former professor of film studies at Jadavpur University, underlines, Ghatak abandoned the realistic narrative to take cinema outside entertainment and Hollywood influence. It became a “different cultural practice”. He wanted cinema to talk about history, specifically, “to reunite a people with its roots”.

Ghatak does not talk about just Partition, says Mukhopadhyay. Ghatak’s films are a passionate portraiture of a people that has already experienced Partition. The refugees who have arrived from East Bengal have not only lost their homes but also their identity, their history.

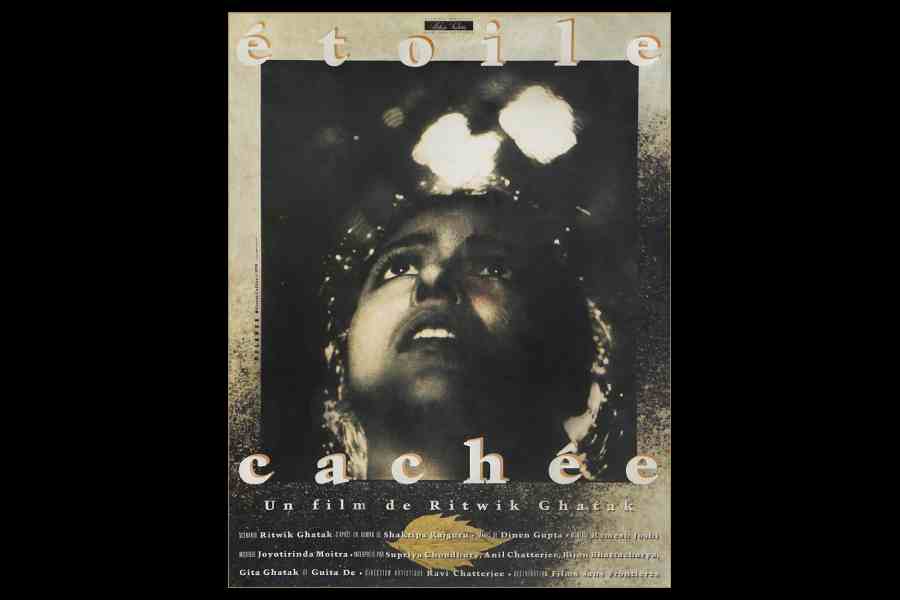

“Ghatak uses mythology, folk culture and melodrama, elements from this part of the world, in his cinema,” says Mukhopadhyay, to reintegrate these people with their past. As the famous low-angle shot in Meghe Dhaka Tara suggests, Mukhopadhyay says, Neeta is the Mother Goddess who is about to be sacrificed.

If a new mythology has to be written for a new time, for which cinema is Ghatak’s medium, its protagonist has to change. The names of the characters in Subarnarekha indicate this clearly, says Mukhopadhyay: Sita marries Abiram, the son of Kaushalya or Bagdi-bou, a woman identified by her low caste.

“The subaltern is the hero of this new epic,” says Mukhopadhyay. It also has a drastically different end from the classical one.

In the contribution he made to cinema, Ghatak can be compared to Bergman, Bunuel, Tarkovsky and Kiarostami, says Mukhopadhyay.

“Ghatak has left us only with his legacy,” says Tridib Poddar, associate professor, department of direction and screenplay writing, Satyajit Ray Film & Television Institute (SRFTI), Calcutta. “Almost 50 years after his passing, we have not been able to discover another Ritwik.”

Ghatak’s truthfulness to his passion, says Poddar, is to be remembered with his contribution to the cinematic language.

“The use of wide lenses, low-angle camera placements, the asymmetrical composition of frames, melodramatic style, and the belief in the collective unconscious — his quest was always to create a form that is close to our emotions, values and traditions,” Poddar says.

“Satyajit Ray commented towards the end of his life that Ritwik was the most ‘Indian filmmaker’ among his contemporaries.”

Ghatak inspired a brilliant group of students at the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII), Pune, with his ideas, Poddar says.

Ghatak’s Marxist political ideology shaped his creative mind. “But we should not see him as a ‘political filmmaker’ like Mrinal Sen. Politics was the soul of his films,” Poddar says. “I believe it is possible to learn language and techniques from Ray’s cinema but not from Ghatak’s; he can only inspire one to find one’s vision.”

Ghatak’s ideology and humanity, within and outside his cinema, give us the strength even now to fight for justice, Poddar says.

Cinematographer Sunny Lahiri underscores how versatile Ghatak was. Ghatak made “epic cinema” but he was also someone who had written the screenplay for Madhumati, the ur-rebirth film of popular Hindi cinema.

“But the hero is the manager, not owner, of a hill timber estate and the heroine, a tribal woman,” Lahiri says. The class hierarchy could be challenged within popular connections, too.

“Ghatak was rooted in his own reality. He was ‘hyper-local’,” Lahiri says. That made him universal. “His films were about the human condition.”

The repertoires of music and sound were stunningly versatile in Ghatak’s films, Lahiri says. Apart from Shankar singing Hamsadhwani in Meghe Dhaka Tara in A.T. Kanan’s voice, another scene that could have gone the cliché way, we have in Titas Ekti Nadir Naam just the sound of a woman breathing, signifying her wedding.

Gour Karmakar, now 91, had assisted Ghatak and his crew in several films. “He would compose his own frames,” Karmakar says, talking in particular about the low-angle shots and the hard work that would go into them.

Karmakar will be speaking at an exhibition on Ghatak, to be inaugurated at Jibansmriti Digital Archive, Uttarpara, on Monday.