They look at traditional folk form as a way of feeding their own theatre. So they often incorporate the forms, they incorporate the images, they incorporate the styles but they don’t necessarily incorporate the people or the language.” That was Anjum Katyal, writer-translator-editor, essentially talking about Habib Tanvir’s contribution, only foregrounding it as the obverse to “them”, who in this case is the typical urban theatre director.

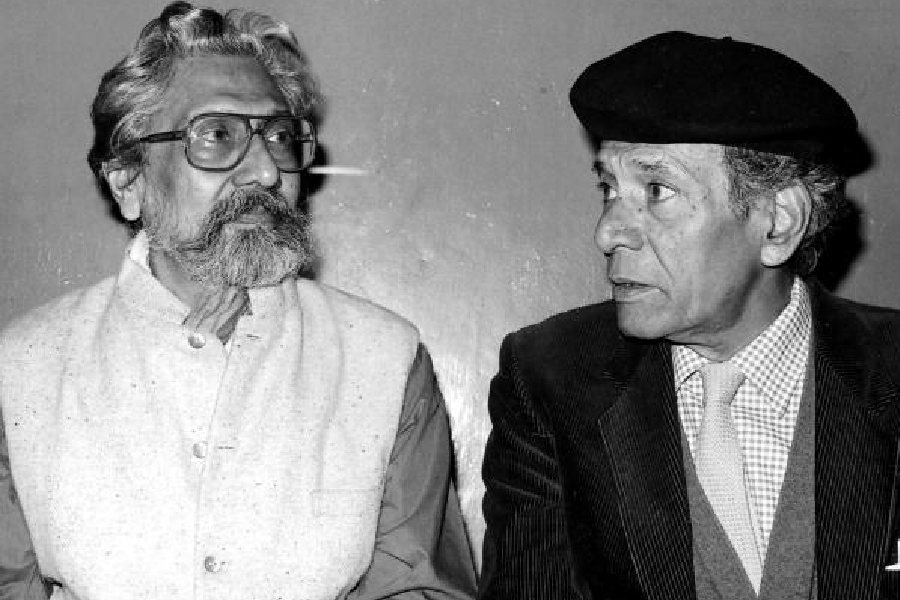

Katyal is one of two editors of the recently published book, Habib Tanvir and His Legacy in Theatre: A Centennial Reappraisal, which is a multi-layered exploration of Tanvir and his work by scholars, critics, theatre practitioners and peers. She has edited this jointly with theatre scholar Javed Malick, Tanvir’s nephew. Malick died on July 24 this year.

Tanvir chose the Naacha, which is a folk theatre form. Katyal proceeds to tell the story of how he came to pick it. How it all stemmed from his small-town roots — Tanvir grew up in Raipur — from living in a large family very involved with the local culture, be it the mushairas or all-night folk performances.

Katyal continues, “Very rarely do we see actual rural trained actors speaking their own languages and performing on urban stages, international stages... Tanvir saw that Naacha actors had tremendous talent. For spontaneous improvisation, for comic timing, they could sing, they could dance, and that they were capable of understanding very complicated and so-called modern textual matter as well.”

Sometime, when he was still in Europe, all of this came together in an epiphanous moment and the soul of Naya Theatre was conceived. The first play Tanvir staged was the classical Sanskrit play Mrichchhakatika which he turned into the Chattisgarhi Mitti ki Gadi. Naya Theatre is the name for the professional touring company he founded in 1959.

One of Tanvir’s most controversial plays is Ponga Pandit, also known as Jamadarin, revolving around the clash between an upper-caste man and a Dalit woman. In one of the scenes that the protesters took exception to, a Brahmin pandit was depicted lighting an incense stick with a burning bidi. Elsewhere, a sweeper was shown carrying away an idol in her basket. “It was all about making fun of religious ritual and it was also about showing how the subaltern Dalit very cleverly outwits the system, the religious system that is designed to keep her in her place,” says Katyal.

In 2003, just before the BJP came to power in Madhya Pradesh, Naya Theatre had been touring the state with the play. The performances were disrupted by BJP workers at multiple places, slammed for being anti-Hindu, all of it arising from the mistaken belief that it was written by a Muslim. The play was actually a Chhattisgarhi folk play, written sometime in the 1930s.

The then incumbent Congress chief minister Digvijaya Singh, who had at first invited them to stage the play, later withdrew support. A report in The Telegraph from October 2003 quotes Tanvir as saying: “After performing in six towns of Madhya Pradesh we arrived in Gwalior for our performance. The moment there was a reference to the Babri Masjid as a turning point to communalism, there was trouble.” In this context it must be remembered that a Naacha play does not have a fixed script; actors improvise and incorporate issues from current news.

There are a host of Tanvir’s plays that would resonate with audiences today. But Katyal chooses to talk about perhaps the lesser-known Bahadur Kalarin, which was apparently Tanvir’s personal favourite. Kalar is a caste of rural brewers and the

play is a folk legend from Sorar, Chattisgarh.

While Bahadur Kalarin is a very much local play with echos of Oedipus, Kamdev Ka Apna, Basant Ritu Ka Sapna is Tanvir’s adaptation of Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream, and Zahreeli Hawa is based on the Bhopal Gas Tragedy.

In Tanvir’s centenary year, there have been stagings aplenty of his plays and plays about him, theatre masterclasses, panel discussions. Some of these will be hosted in Calcutta over the next few days.

Which brings us to the question of Tanvir’s relevance today. Katyal seems to think of him as the champion of subversion, be it in Agra Bazar or Mitti ki Gadi or Charandas Chor. She says, “He wasn’t just making art for art’s sake, getting kudos being feted by the elite and going to fancy parties and having his name published in the papers... He felt that we have the wrong idea, we do not understand the sophistication in the villages, we think they are dumb or they are stupid or they are less evolved than us but that’s not true. And he wanted to prove that.”