If there was one political leader whom his people knew without being able to unravel, one they admired but without becoming anything like “close” to him, one who was cherished as one might cherish a work of surpassing art, it was Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee.

He was minister for information and culture in Jyotibabu’s cabinet when I first met him. He had been described to me sometime prior to that by a woman journalist I greatly respect for her discernment as “a singularly handsome man” and, as he received President K.R. Narayanan (in whose office I was then working), I could see

she was right.

Looks have to do with an inner self no less than how “one looks”. As Buddhababu accompanied President Narayanan on a visit to Jorasanko, his mind sparkled, almost with the excitement of a university student. I could see he knew his Tagore.

“I have often wondered,” the President said, “has Tagore used the phrase ‘In this haven of freedom let my country awake’… or ‘heaven of freedom’?”

A gentle smile flashing across his face, Buddhababu took no more than a second to say, “Heaven, not haven”, and then proceeded to recite the immortal verse in its original.

Some six years later, President Hugo Chavez of Venezuela came visiting India and, of course, as any communist leader visiting India would, he came to West Bengal. By then I was working in Kolkata, entirely courtesy Buddhababu for it was he, as chief minister, who had asked Prime Minister Manmohan Singh to send me to its Raj Bhavan.

At a giant rally in the city, Chavez recited the same iconic poem in Spanish and his interpreter, a sincere Bengali, struggled to render the poem from the Spanish into Bangla.

The mass of humanity present knew the poem well and became impatient with the interpreter. It did not want to hear an “anyhow” rendering of the work in Bangla, it wanted the genuine thing.

Buddhababu, seated quietly to a side, then rose and telling Chavez something in his ear, proceeded to the mike and, replacing the interpreter, recited “Chitta jetha bhoyshunyo” from memory.

The concourse erupted in joy. And Chavez was thrilled – his Spanish rendering was being restored to Bangla.

Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee was an artist in politics, a curator of public discourse and debate. Had he not been impacted along with his generation by Marx, and had he not joined politics, he would still have been a man of few words and very restricted hand gestures but would have commanded the field he occupied – I believe which would have been academe.

He would have been an ardent student, a wonderful teacher, with students who would have hung on his every word – few and far between as those would have been — looking for deeper meanings.

And with wisps of tobacco smoke surrounding his elegant head of first black, then grey and then white crown, he would have been the toast of any campus.

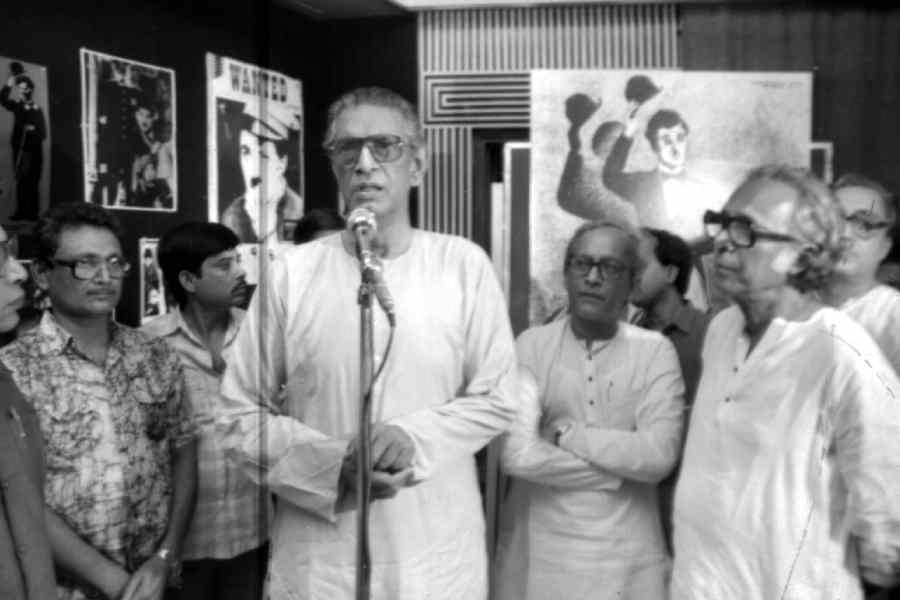

Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee with Satyajit Ray and Mrinal Sen at the Inauguration of an exhibition at Nandan to mark the birth centenary of Charlie Chaplin in 1989 Sourced by The Telegraph

There is one other field he would have been a master of: directing high art cinema.

He once told me, “Don’t go to see any Bengali film without asking me. I will tell you which to go to, which to avoid. Some of them are plain rubbish.”

As a film director, he would have towered. His films would have had character, psychology, humanity. Above all, they would have had engaging dialogue — in short sentences. And he would have stuck to black and white. Colour, he would have said, is bogus. He loved to use that word – “bogus” – for persons and things.

But it is India’s and Bengal’s great good fortune that he chose to be in politics where his transparent sincerity, his patent integrity and his total commitment to his ideology made him more than an asset – a treasure. Throughout my five-year tenure in the state, I had in Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee a chief minister I could respect, trust, and work with in mutuality.

The sharp conflict between us over Nandigram was to threaten the cordiality with which we started out; it could not and did not in the slightest reduce my respect for him and my admiration. But even in the white heat of Nandigram, I understood that such negativity as had crept into our equation was driven by the politics of compulsions and obligations.

I cannot forget two episodes. I once told him that a certain party functionary whose reputation was hurting the government should be sacked by him. “My party is the Communist Party. It is not a Nazi party. We do not work like that. We have procedures.”

I could think of some stern procedures adopted by the Communist Party (Marxist) but I was sobered by his reply. It is another story that the person concerned was to betray him and his party later.

And once when I saw that he was clearly unhappy with my statements on Nandigram, I said to him, “Buddhababu, you can ask for another governor, your party is in alliance with the Congress. That is how you were encouraged to ask for me to be posted here. You can in the same way ask for another governor.”

He was silent for a while and then said: “I will not do that. I am not such a person.” What could be more civil than that?

As a committed Marxist, a loyal member of his party, a steady soldier of the Left, he remained an independent thinker, judging people and observing processes from the standpoint of what was bhadra, bhalo. Something in him revolted against all that was in poor taste.

As governor and chief minister, we frequently exchanged letters, official, needless to say to each other. Mine would be longer than necessary. His shorter than they need have been.

Once Buddhababu asked me which year I was born and, when I said “1945”, he merely said, “I was born in 1944.”

More need not have been said. He was older, he knew the world that much better.

I cannot conclude without saying something in partial modification of what I have said at the start of this tribute. There was one person who understood him and whom he understood and was really close to – Anil Biswas, almost exactly the same age as him. The day Anilbabu died, something in Buddhababu closed up. One needs a thought-partner in life. He now had that only in Meeradebi, his remarkable wife.

Leaving his family behind would have torn Buddhababu’s departing heart. But then he being he, he would not have shown it.

“Ayyo,” I said when I heard of his demise. That Tamil word says it all. Ayyo, pity us, dear Time-Keeper, for you have bored a deep hole into our country’s civility.