History can be unkind. Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee, who died on August 8, was a victim of this bizarre unkindness. When he was alive, Bhattacharjee was often remembered, even by his comrades, as the man who sounded the death knell of the Communist Party of India (Marxist) and of the communist movement in West Bengal. There is an element of truth in this assessment but it does not capture in entirety what Bhattacharjee attempted to do and failed to do.

Bhattacharjee was West Bengal’s second communist chief minister. But this phase of his life cannot be appreciated without a knowledge of his formative years. The idealism associated with communism informed Bhattacharjee’s consciousness from his adolescence. The communist poet Sukanta Bhattacharya, whose poems are part of any educated Bengali’s memory, was his uncle. It was perhaps foretold that young Buddhadeb would join the communist movement, which he did as a student of Presidency College in the early 1960s. He started as an activist of the Student Federation of India but very soon became a whole-timer of the CPM. From then, Bhattacharjee’s identity and loyalty were inextricably tied to the party.

This point is important as the CPM was and is a Stalinist party. This orientation was pivotal in the fashioning of Bhattacharjee as a communist.

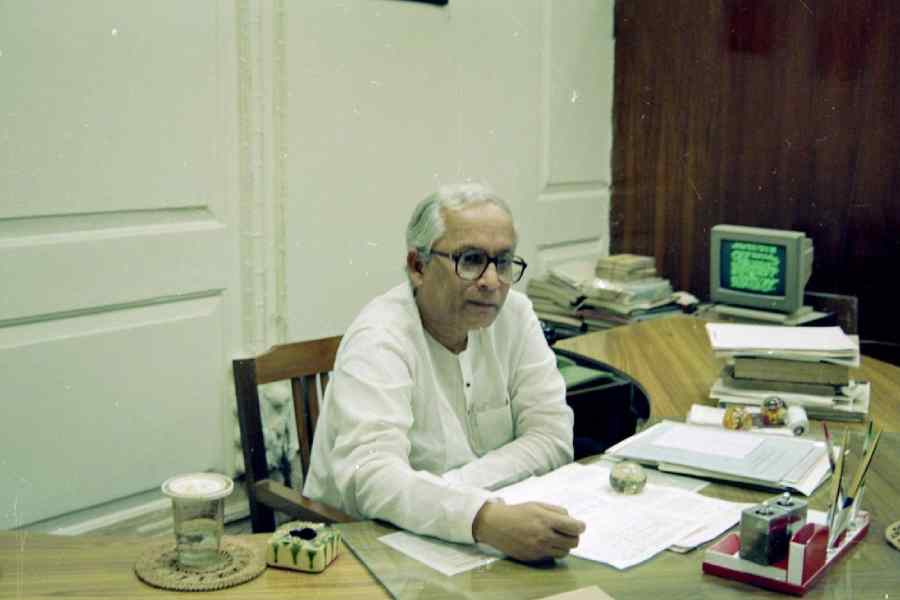

The CPM was and is a Stalinist party. This orientation was pivotal in the fashioning of Bhattacharjee as a communist TT Archives

The CPM in West Bengal, when Bhattacharjee was coming of age in the party, was controlled in terms of the party organisation by Pramode Dasgupta, who was Bhattacharjee’s principal mentor in the party. In fact, Bhattacharjee, Biman Bose and Anil Biswas formed a trio with strong bonds with Dasgupta. The latter believed that the party should dominate every sphere of life in West Bengal — from politics to education and culture. Dasgupta, in the way he operated, was a textbook machine politician with pronounced anti-intellectual attitudes. Every sphere, according to Dasgupta, would be run by CPM cadre or by party fellow travellers.

And so it was over the three decades that CPM monopolised the reins of power in West Bengal. Bhattacharjee imbibed these ideas and practices. Any kind of dissent was of course not permitted in a Stalinist party. There is no evidence to suggest that at this stage of his life, Bhattacharjee was uncomfortable with the way Dasgupta ran the party and the ideas he implanted in the minds of cadres. Bhattacharjee’s loyalty and commitment to the party earned for him important portfolios in successive Left Front governments led by Jyoti Basu.

Bhattacharjee’s loyalty and commitment to the party earned for him important portfolios in successive Left Front governments led by Jyoti Basu TT Archives

In the early 1990s, he resigned as minister in a fit of pique. The real reasons for his exit are not known and possibly will never be known. What is more telling is the fact that he was recalled to the ministry. This was the first and unmistakable signal that Bhattacharjee was being considered as a successor to Basu. Bhattacharjee told Ashis Chakrabarti, a very senior journalist and political commentator, that Basu’s chair was not for him. This was, at best, false modesty, at worst, a piece of dissembling. It is inconceivable that Bhattacharjee was unaware of a succession plan. He was, given his growing stature within the West Bengal party, probably one of the makers of such a plan.

With the coming of the 21st century a new and arguably the most important phase of Bhattacharjee’s career began. He succeeded Basu as chief minister seamlessly. It was perhaps then that reality dawned on Bhattacharjee and the scales of ideology fell from his eyes. The reality was stark: steeply plummeting employment opportunities in industry, which meant that the aspirations of the youth whose parents had benefited from the prosperity engendered in the rural world by the Left Front’s agrarian policies — irrigation, high-yielding seeds and fertilisers, multiple crops and so on — and land reforms (giving land rights to small tenant farmers, sharecroppers and landless labourers) were being frustrated. Added to this was the perilous state of education and public health.

With the vision for a new West Bengal, Bhattacharjee decided to take on these issues and veer away radically from the path trodden thus far by the CPM and the Left Front. He was rushing into dangerous terrain. But he was convinced that he had no other option.

With his vision for a new West Bengal, Bhattacharjee was rushing into dangerous terrain. But he was convinced that he had no other option TT Archives

Bhattacharjee went about what he saw as his responsibility to West Bengal with great gusto. In the process, he had to slough off the ideological beliefs that had sustained him since his youth. From seeing private capital and private profit as evil, he began to woo capitalists to invest in West Bengal. To reach out to capitalists, he even befriended Aveek Sarkar, the then editor in chief of the ABP group — a media house which the CPM and therefore Bhattacharjee had previously treated with hostility and unqualified contempt.

Bhattacharjee began to speak a different language, which was contrary to the usual CPM speak. For this he earned respect from many capitalists and even from Manmohan Singh, all of whom saw in the new incarnation of Bhattacharjee a breath of fresh air. But the most substantive result of this turnaround was Ratan Tata’s decision to set up the manufacturing unit for Nano in West Bengal.

This is where the CPM’s and therefore Bhattacharjee’s own past caught up with him and his plans. The availability of land is one of the necessary conditions for setting up a factory. In West Bengal, land was not freely available because the Left Front government’s land reforms had created rights on land. Different sections and layers of the rural population had legally vested rights on land. In a typical free market situation, a capitalist would have proceeded to get the land required to set up a factory by buying land from peasants at a negotiated market determined price. But given the situation in West Bengal, it would be a time-consuming and an almost impossible task for a capitalist investor to negotiate with every single right holder in a chosen and convenient area and buy contiguous pieces of land to set up a factory. The prevailing conditions demanded that the State step in to acquire the land for the Tatas.

The Tata Motors factory in Singur when it was coming up, in August 2008, before the Tatas pulled out TT Archives

Bhattacharjee proceeded to do exactly this and acquired land by dispossessing peasants in Singur, near Kolkata. There were questions raised about the compensation given to the peasants. There was a further anomaly: the land had been acquired to be used for public purposes but was being given to a private company. In a Stalinist manoeuvre, Bhattacharjee brushed aside such questions. The common assumption was that the land meant for the factory had been acquired by using State power. Thus, the paradox of trying to usher in capitalism through means that Stalin had used during forced collectivisation in the Soviet Union. One could argue that given Bhattacharjee’s Stalinist past, there was nothing surprising in the methods he adopted.

Acquiring peasant land for the Nano factory in Singur created a groundswell of peasant discontent. Mamata Banerjee took full advantage of this situation to launch a campaign that made the Tatas take the Nano project away from West Bengal. Ratan Tata, who Bhattacharjee implicitly trusted, as a shrewd businessman had a plan B in place, as he had already begun negotiations with the Gujarat government under Narendra Modi.

Bhattacharjee campaigning at Ranaghat, in 2011 TT Archives

Bhattacharjee’s dream was about to turn into a nightmare. Peasant discontent against land seizures turned into peasant resistance in Nandigram, where agricultural land had been acquired to create an SEZ. Bhattacharjee’s government and CPM cadre let loose a reign of terror in Nandigram. Violence led to loss of lives, which galvanised large sections of the people, including members of the intelligentsia, even left-leaning ones, to come out on the streets to protest against Bhattacharjee’s use of violence.

The writing was on the wall: Bhattacharjee politically was on borrowed time. A populist leader was waiting in the wings.

Bhattacharjee had dreamt of a new and rejuvenated West Bengal. To fulfil that dream, he had surrendered some of the beliefs that had been integral parts of his identity. There was something heroic in this attempt. The collapse of communist regimes globally had no doubt helped Bhattacharjee to reconfigure his thinking and to abandon some of his hard-held prejudices. But he could not win the battle with his past and his party. The violence embedded in the functioning of the CPM proved to be Bhattacharjee’s final undoing.

In a very famous passage, Marx wrote that men make their own history but they do not make it just as they please. The dead hand of the past hangs over them. Bhattacharjee had tried to make history but the dead and deadening hand of his and his party’s past made him a prophet doomed.

Rudrangshu Mukherjee is Chancellor and Professor of History at Ashoka University. The views expressed are personal.