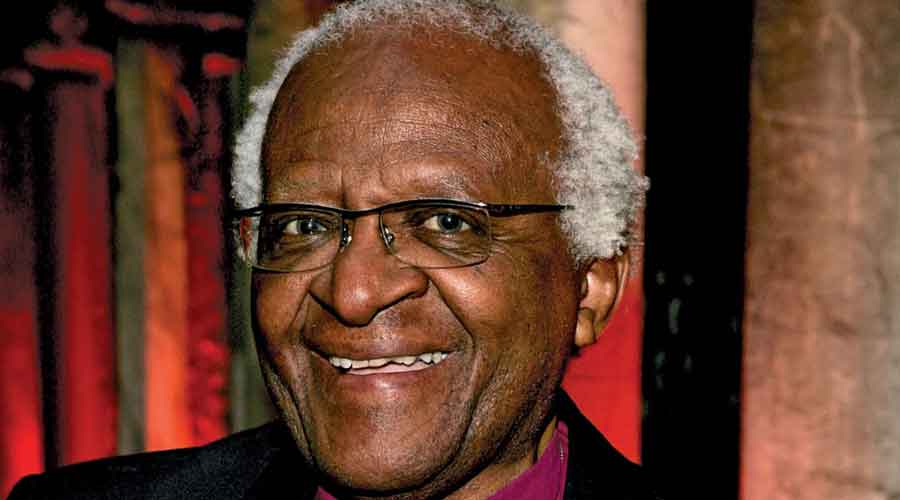

I have been thinking a great deal about South Africa these past few weeks, in part because of the Test series being played there, but mostly because of Archbishop Desmond Tutu, with whose passing the last of the great stalwarts of the anti-apartheid struggle has left the stage. Although best known for the work he did in South Africa, he commanded respect even when he spoke about injustice and oppression in countries that were not his own. He perhaps came closer to being the world’s conscience than any of his contemporaries.

I first saw Desmond Tutu on a television screen in January 1986. I was then teaching in the United States of America, and the priest had come on a visit of that country seeking to shake America, and Americans, from their tacit and, sometimes, explicit support for the apartheid State in South Africa. Tutu believed that economic pressure by the West might compel the ruling regime to finally take steps to end racial discrimination. He met corporate chiefs, including the head of General Motors, as well as the presidents of America’s greatest and best endowed universities, urging them to withdraw their very substantial and profitable investments in South Africa.

On this trip to the US, Tutu came across as a man of charm as well as courage, with an engaging, witty presence that belied the steely spine that lay beneath. Apart from meeting the wealthy and the powerful, Tutu also interacted with those who had taken part in the American civil rights struggle of the 1960s. There were frequent comparisons with Martin Luther King, which the South African rejected, telling reporters that, among other things, MLK was far more handsome than he, pointing as he spoke to his short, rotund, figure and unkempt hair.

Among the American universities which had invested in South Africa was Yale where I was based. Tutu’s visit galvanized the students as well as a section of the faculty, who approached the Yale Corporation to divest its holdings in South African companies. The Corporators haughtily refused. So the students occupied a large plaza outside the Beinecke Library and erected shacks made of wood and tin, where they sat, sang, raised slogans and made speeches. They put up portraits of Nelson Mandela, who, having been in prison for more than twenty years, embodied in his person the struggle and the sacrifice of the anti-apartheid movement.

These few months at Yale were the first time I had been out of India. Although I was in my late twenties, I had not—till I saw Bishop Tutu speak on American TV—been much concerned with what was happening in South Africa. It was not as if I was apolitical, since rising caste and religious tensions in my own country certainly did engage me. I had kept my eye on turbulent political events in Vietnam, Iran and other places, but not, somehow, in South Africa. I suppose I might blame it on the Indian press, which rarely carried any reports on that country, perhaps because we had no diplomatic ties with the racist regime there. Now, after hearing Tutu on the television and reading reports of his speeches and witnessing their impact on the mostly white students of Yale, my interest in South Africa was belatedly stoked.

After returning to India, I began to follow South African politics more closely. The movement for sanctions was beginning to take effect. Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan, previously unwilling to criticize the apartheid regime, began to make some noises. Nelson Mandela was still in prison, but allowed to meet the odd foreign visitor. They included the former Australian prime minister, Malcolm Fraser, to whom Mandela’s first question was: “Is Don Bradman still alive?”

In 1991, I was in London where, at the home of a friend, I met the Anglican priest, Trevor Huddleston, who had been expelled from South Africa in the 1950s because of his criticisms of apartheid. In his time as a parish priest in Johannesburg, Huddleston had mentored many gifted young men, Desmond Tutu being one, and the jazz musician, Hugh Masekela, being another. Now in his late seventies, the once fiery campaigner was frail and visibly ailing. When asked by another guest at the dinner how his health was, Huddleston replied: “I hope to see apartheid dead before I am.” Huddleston got his wish, visiting South Africa briefly after Nelson Mandela became president in 1994.

Between 1997 and 2009, I myself visited South Africa on five occasions. On these trips, I met some remarkable figures of the struggle against apartheid. They included the poet, Mongane Wally Serote, who was in charge of a parliamentary panel to nurture arts and culture; the sociologist, Fatima Meer, still active and alert despite old age and infirmity; the jurist, Albie Sachs, who had lost an arm and an eye to a bomb attack by the South African security forces but yet exuded zest and authority; the historian, Raymond Suttner, devotedly running an academic journal even as his face showed signs of the savage torture he had undergone in prison. They, and others like them, had heroically put the wounds of history behind them and were now working collectively to construct a full-fledged and properly multi-racial democracy.

These individuals were notable for their bravery, their resolution, their intellect, and — perhaps above all — their utter lack of rancour. They came from diverse racial backgrounds: African, Indian, Coloured, White. They represented the coming into being of a ‘Rainbow Nation’ (a term, incidentally, coined by Desmond Tutu). This, I thought, was what it must have been like to be a teacher, a social activist, a civil servant, a judge, in the India of the late 1940s and early 1950s, fired by idealism, inspired by the great leaders who lay above them.

On my visits to South Africa, I mostly interacted with writers and scholars, and never came close to seeing (let alone meeting) Archbishop Tutu. However, in 2005, Tutu came to Bangalore on a private visit, and I found myself invited to a small dinner in his honour. I had him to myself for about fifteen minutes. We first spoke about Sachin Tendulkar, whose deft footwork and thrilling stroke play against the South African fast bowlers he greatly admired. Then I told him of my meeting with Trevor Huddleston. This prompted the Archbishop to say, wistfully and lovingly: “Trevor laughed like an African — with his whole body.”

I would have been saddened by Desmond Tutu’s death even if I did not have those scanty personal connections to him—the memory of those student protests in America that had been inspired by him, and the brief meeting in my hometown two decades later. For he was perhaps the last person alive to be recognized as a moral authority in his own country, and in other countries too. He was the conscience of South Africa, who directly confronted the racial brutality of the apartheid regime and openly criticized the corruption and cronyism of the post-apartheid State run by the African National Congress as well. Tutu spoke out against injustice wherever it occurred, whether conducted by Jewish settlers and the Israeli State against the Palestinians, or against the Rohingyas in Myanmar by a regime led by his fellow Nobel Laureate, Aung Saan Suu Kyi. He even took to task his own Anglican Church for its enduring homophobia.

Tutu’s life and legacy have some salutary lessons for our own country. Particularly relevant to India is his passionate commitment to inter-religious harmony. A man of the cloth, a priest who first became a Bishop and then an Archbishop, he was remarkably undogmatic in the practice of his Christianity. As he once said, with regard to his own appreciation of exemplary individuals from other religious traditions, “God is not a Christian.” And God is not a Hindu either.