Politics, literature, cinema, football, or fish. The passions Malayalis and Bengalis share are legion. Bengali filmmakers, littérateurs, and their famed characters have been household names even in Kerala’s tiny villages. Whatever happens to Bengal used to be keenly watched by Kerala. Emblematic of this special relationship was a monumental poem, “Bengal”, penned in 1972, which became a milestone in the history of Malayalam’s modernist political poetry. The poem mirrored the tumultuous Bengal of the late 1960s and 1970s, which witnessed the violent Naxalite uprising and the brutal State repression against it. As it enters its fiftieth year, the about 800-word poem is being debated and discussed, once again, for its riveting political and poetic dimensions and the way West Bengal has changed during this period. It was the first significant poem by K.G. Sankara Pillai, who penned it when he was a 25-year-old lecturer in Malayalam literature and a fellow traveller of the Naxalite movement. Pillai, who has since emerged as one of Malayalam’s most respected contemporary poets, is the recipient of 2021’s prestigious Gangadhar Meher National Award for poetry instituted by Odisha’s Sambalpur University.

The poem, “Bengal”, is a first-person narration about the anguished, blind Kaurava king, Dhritarashtra, during his autumn, desperately seeking from his informant, Sanjaya, news about his children and grandchildren living in violence-torn West Bengal where the poor peasants’ uprising was spreading like a devastating cyclone. “Dhritarashtra was the symbol of unbridled and ruthless power. But all that the selfish dictator was concerned about was his family. For him, anything that affected his children was a blow against his authority. He represented the arrogant, selfish yet cowardly Indian bourgeoisie. Yet, the poem was neither a paean for the Naxalite movement. It carried my self-doubts and lack of complete faith in its ideology and ways. It’s superstitious to believe that one ideology could address all our problems. “Bengal” inhabits my split mind, caught between faith and doubt. So my Dhritarashtra was a collective trope that bore me too. More than a revolutionary poem, I think of it as a document of the deep political and personal fissures and fault lines of the period,” says KGS, as he is known. The 74-year-old poet has translated many foreign-language poems into Malayalam and retired as a college principal.

“Bengal” proved prophetic when, three years after it appeared, the then prime minister, Indira Gandhi, clamped the authoritarian Emergency and her nepotistic affection toward her son, Sanjay, led to disastrous effects for the country and herself, much like what happened in the story of Dhritarashtra and his capricious sons. The poem, with the ruthless patriarch as the protagonist who goes through extreme fear, agony, and solitude during his last days on account of his own atrocities and the recurring metaphors of autumn, ran strikingly parallel to Gabriel García Márquez’s novel, The Autumn of the Patriarch, which had been called “a poem on the solitude of power”. But KGS hastens: “Don’t accuse me of plagiarism. Marquez’s novel came three years after my poem. It should be some strange revelation that united the two works.”

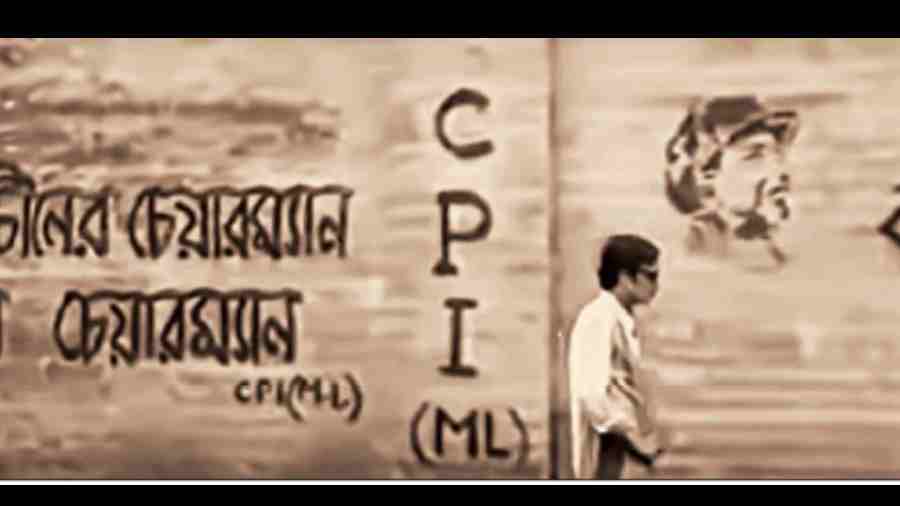

KGS penned the poem when he was closely associated with the nascent Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) movement, especially with its cultural activities. He was inspired by the Naxalbari peasants’ uprising. A visit to Calcutta in 1972, on an invitation from the Association for the Protection of Democratic Rights, which was fighting for human rights during the repressive rule by the former chief minister, Siddhartha Shankar Ray, also triggered the poem. “Kalyani Bhattacharyya was the ADPR president. Its activists took me from Howrah station through so many narrow gallis to a secret place, which I found unbearably conspiratorial,” he recalls.

Immediately after publishing “Bengal”, KGS was subjected to frequent interrogations and raids by the police. The magazine, Prasakthi, which published the poem, was edited by Pillai and was seized by the police and closed down after the third issue. “A stupid policeman also took away my three volumes of Marx’s Theories of Surplus Value only because they had red covers. Another asked me if I was running a publication called Parasakthi, mistaking it for Prasakthi (Relevance). I told him no and that I don’t believe in Parasakthi (Almighty). The worst torture I suffered was when a secret police guy made me listen to his unbearable English translation of my poem for it to be sent as proof of its subversive nature to his bosses in Delhi,” laughs KGS.

Half a century after publishing “Bengal”, what does come to his mind when he thinks of the state of West Bengal, which has seen the eclipse of the Left ideology that hegemonised the state for a long time? “Now, only great icons like Sri Ramakrishna, Vivekananda, Tagore, Jamini Roy, Ray, or Ghatak come to my mind,” says KGS. “They represent the great renaissance and the waves of creativity that it unleashed. Political Bengal no more comes to my mind. As for the Left’s eclipse, I consider these icons as the real Left. The so-called Left parties of today, which clamour for power and are divorced from Bengal’s rich cultural traditions and the creative genius of the renaissance, are not Left at all. It is no different in Kerala. Neither Marxism nor Maoism can survive without being organically linked to the region’s cultural legacy.”

B. Rajeevan, a prominent critic and KGS’s close comrade during their Naxalite past, thinks the poem, “Bengal”, is still relevant as dictators continue to emerge and there is also growing people’s resistance against them. “Shouldn’t we dismiss this poem as insignificant as the failed revolution that inspired it half a century ago? Not at all, because this poem’s emotional apparatus continues to connect with contemporary life’s virtual intensities when dictators thrive and resistance movements also gather strength.” According to Rajeevan, most of the intellectuals and middle-class activists who had backed the uprising have returned to the comfort of their homes as law-abiding gentlemen, celebrating the “flourishing of democracy” worldwide, repentant of their “wayward past”.

KGS, who has been associated with many human rights movements, feels that the MarxistLeninist movement did not do justice to those who laid down their lives for it or to their families. “Kanu Sanyal committed suicide. Charu Majumdar’s impoverished family was not supported after his death. Those who still brag about being Maoists are liars.” Yet, according to him, Bengal wouldn’t lie dormant for long, given its great cultural legacy. “Bengal is like a cinder buried under ash. Just a good wind would be enough to make it flame again”.

M.G. Radhakrishnan, a senior journalist based in Thiruvananthapuram, has worked with various print and electronic media organisations