Government departments in India excel in circular arguments. The ministry of social justice and empowerment explained the drastic reduction of funds allocated to the Self Employment Scheme for Rehabilitation of Manual Scavengers from over Rs 4,600 crore in 2013, when the law prohibiting employment as manual scavengers was enacted, to five crore rupees in 2017 — it has since been raised to Rs 20 crore — by saying that the government agency in charge of implementation had a lot of unused funds. The logic is flawless. If the government fails to, or is not bothered enough to, help manual scavengers, the government shall naturally tighten its purse-strings. The United Progressive Alliance, however late in the day, had at least started a process of righting an ancient wrong; the National Democratic Alliance headed by the Bharatiya Janata Party simply focused on reducing the funds for it. Whether or not this chimes in with Hindutva ideology — the majority of manual scavengers are Dalits — it certainly sits oddly with the prime minister’s passionate drive for Swachh Bharat. This passion offers as many rhetorical opportunities as visual, from eloquent speeches about an open-defecation free India to broom-fisted politicians led by the prime minister inspiring the nation to be clean.

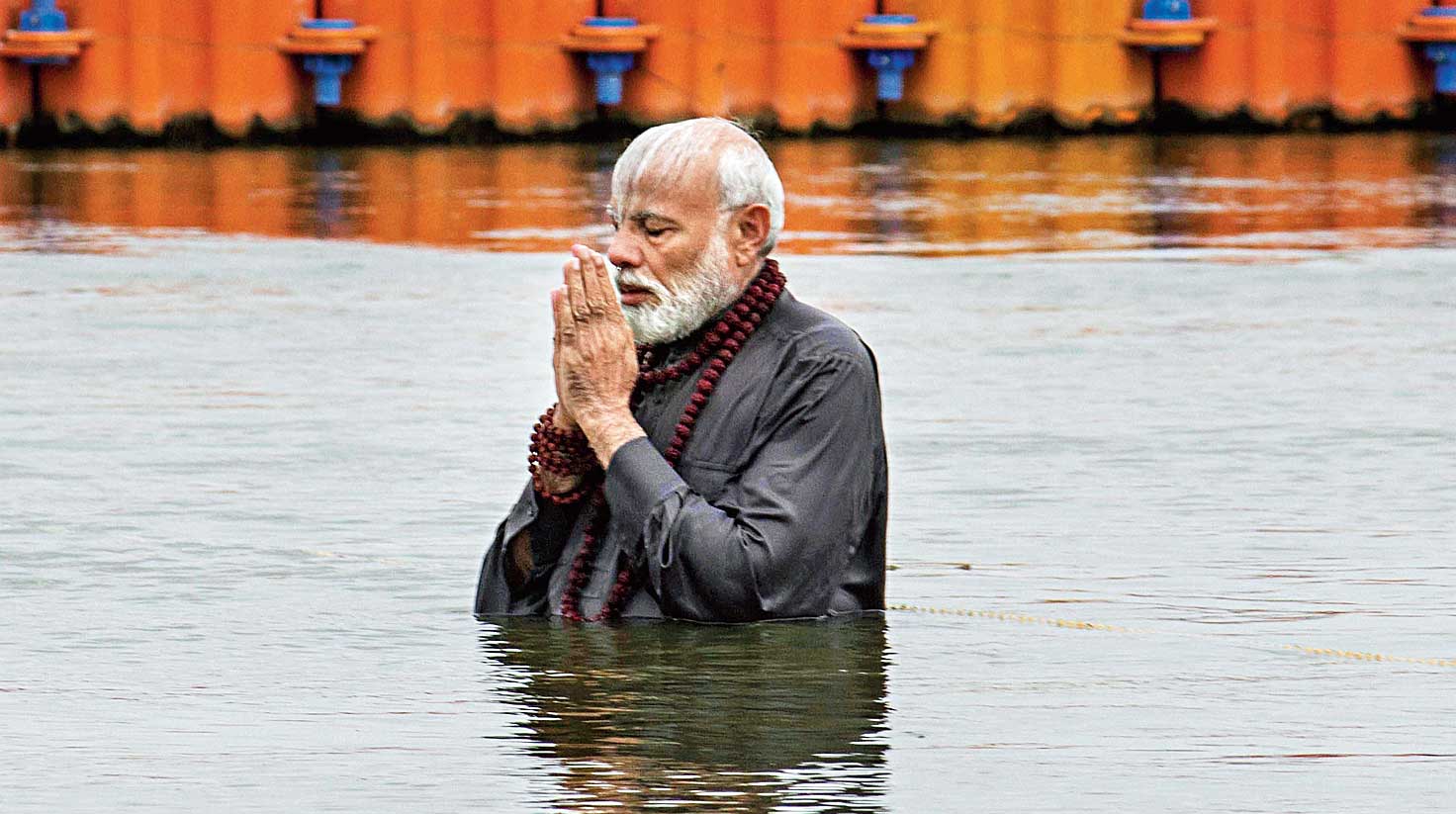

The latest photo op was designed for the Kumbh mela, where the prime minister was televised washing the feet of a few sanitation workers, offering his tribute to ‘his’ karmayogis who kept the mela clean. Perhaps the image was meant to obliterate the fact that two leaders of the association of sanitation workers had been detained a couple of weeks earlier and threatened with the National Security Act. They were freed, but the need to silence them was reportedly felt because the manual scavengers are demanding proper daily wages and overtime, adequate equipment for health and safety, and insurance. The trick has always been to underestimate officially the numbers of manual scavengers by lakhs. It keeps them invisible. But building toilets in rural areas to stop open defecation has increased, not reduced, the demand for cleaners of dry latrines. Without spending on sewage systems in villages as well as on waste treatment units to prevent the pollution of rivers and streams, making India open-defecation free will be meaningless. And these budgetary allocations should be made alongside usable amounts for the rehabilitation of manual scavengers.