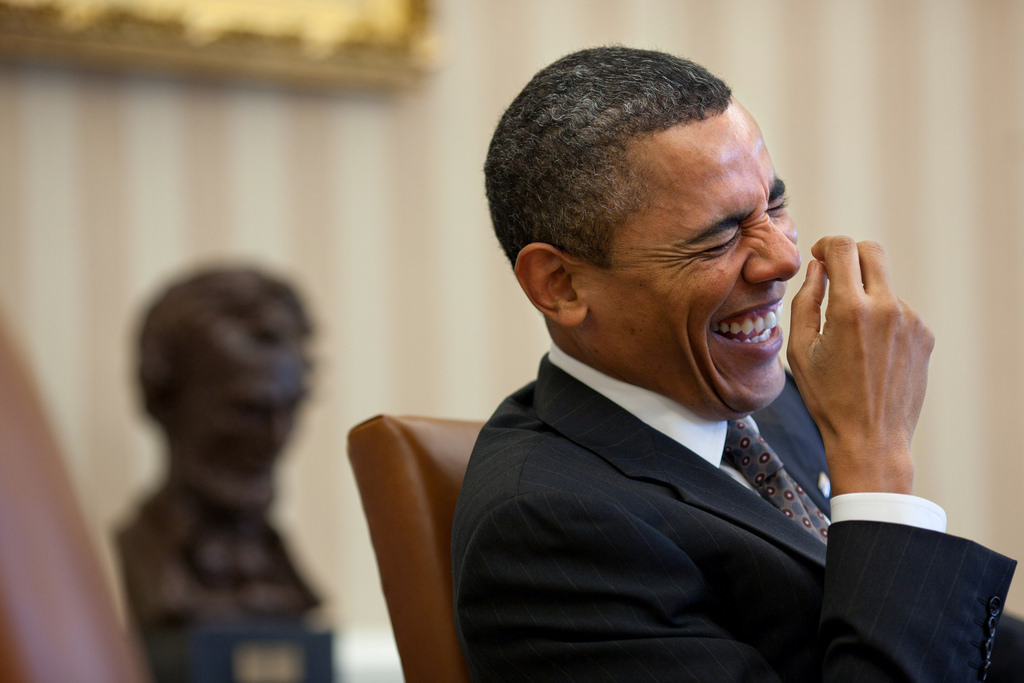

In the cornucopia of riches that the magic of the internet has brought to our fingertips, few things are as delight-giving as comparing YouTube videos of the present president of the United States of America with those of his predecessor. When doing this, one thing that never ceases to give your humble scrivener joy is the vast difference in the nature of the humour the two men employ. Whilst Barack Obama was never averse to taking digs at himself, often using them as a means to draw attention to his adversaries’ po-faced attacks on his person and policies — by, for example, bringing up the issue of his “Kenyan birth and citizenship” or his “socialist” views — the present incumbent’s attempts are eerily reminiscent of the neighbourhood bully taking away the nerdy kid’s candy, then laughing and going ‘Nyah! Nyah! Nyah!’ Donald Trump uses ridicule and slander to belittle others, especially those whom he sees as opponents or enemies (who are, at the time of writing, pretty much everyone), and thinks it hilariously funny; Obama, in sharp contrast, used his oratorical powers and ready wit to lighten a situation and lift a mood, often at his own expense.

Two of the traits that seem to be shared by every truly gifted or great individual I have encountered, whether through their words (or works) or in the flesh, are humility and a sense of humour. The humility I speak of is not the humblebrag variety of faux self-effacement that plagues us on social media, but rather the genuine sense of wonder that the real savant experiences when confronted with the limitless expanse of knowledge. It was this sense of humility that led an Isaac Newton to say that he had been able to look further into the mysteries of nature because he had stood on the shoulders of giants. It also made the 72-year-old Charles Darwin express uncertainty about his own understanding of the laws of heredity (“inheritance” in Darwin’s terminology) when writing to an unknown correspondent. Even if Gandhi did not say “It would be a good idea” when asked what he thought about Western civilization, the Great Soul’s impish sense of humour deserves a full column by itself in order to be exhibited in all its variegated variety. And who can forget Sarojini Naidu’s quip about the Congress Party having to spend a great deal of money to keep the great man in poverty?

Another facet of the Greats (as I think of them in secret but would never confess to doing so in public) is their ability to take pleasure in the remarkable fact and quotidian miracle of human existence — a joyous delight (ananda) that was central to Rabindranath Tagore’s idea and philosophy of art and life as indeed it was to the cinema of Chaplin, the novels of Dickens and the poetry of Neruda, to mention three favourites. The same qualities of humility, delight, laughter and joy can be found in our own times and lives in the works of scholars and artists such as Romila Thapar, Nabaneeta Dev Sen, K.R. Meera (whose novel, Hangwoman, is one of the finest, and funniest, satires published in recent years), and Ambai, to name just four individuals still living and working among us. The fairly-recently-deceased Mahasweta Devi possessed these qualities in buckets as did her son, the great Nabarun Bhattacharya.

Consider the situation as it now stands in what passes for public life in our benighted land. When is the last time you heard any of our leaders cracking a joke that was not meant to hurt or humiliate someone else? (Think “presstitute”, think “urban Naxal”, think “Pappu”, think “babalog brigade” — the list keeps expanding with every freshly-minted insult.) When last did our beloved defenders of shudh desi manners and mores find something funny that was not a put-down of someone or something else? When, for that matter, did you last hear of a neta having a laugh at his (or her) own expense? Can’t recall? Neither can I.

The author is professor of Comparative Literature, Jadavpur University, and has been working as a volunteer for a rural development NGO for the last 30 years

It’s all serious business now, or so it seems, with no time for a smile or even a bit of a chuckle. Not to mention our eagerness to take offence and be outraged at the slightest pretext. This seems to be true not just for those who belong to the ruling dispensation, their opponents too seem to have drunk from the same cauldron of high-seriousness. As students and farmers and teachers and ordinary women and men are labelled ‘anti-national’ if they question the powers-that-be on even the smallest matter, it might be a good time to look at how others responded to similar situations. One man who was often outraged at what he perceived to be the inequities of his time and from whom we might learn a trick or three was Mark Twain (1835 – 1910), whose wit never flagged even when taking on the biggest “humbugs” (a word he favoured) of his time. When he returned to the United States of America after five years abroad, in 1900, Twain was told he might not be able to vote in the presidential elections. Interestingly, in 1879, he had penned “A Presidential Candidate”, which began “I have pretty much made up my mind to run for President” and then went on to give a hilarious account of his qualifications for the office. “If you know the worst about a candidate, to begin with, every attempt to spring things on him will be checkmated. Now I am going to enter the field with an open record. I am going to own up in advance to all the wickedness I have done…” he wrote and then spoke of “the heartless brutality that is characteristic of me” which included, among other things, the fact that “I am not a friend of the poor man. I regard the poor man, in his present condition, as so much wasted raw material. Cut up and properly canned, he might be made useful to fatten the natives of the cannibal islands and to improve our export trade with that region. I shall recommend legislation upon the subject in my first message. My campaign cry will be: ‘Desiccate the poor workingman; stuff him into sausages!’”

Twain ended his brief piece with the ringing self-endorsement: “I recommend myself as a safe man — a man who starts from the basis of total depravity and proposes to be fiendish to the last.” Reading this over a century after it first appeared, I’m not quite sure whether to laugh at Twain’s satirical wit or crack a wry smile at just how little things seem to have changed since.