The noble bequest of humankind is articulate speech; the ignoble thing about it, very often, is the uses we put it to. It is at that turnstile revving between gift and curse that a newspaper stands — observer, scribe, reporter; interpreter of whisper and scream, babble and baloney; notekeeper to time, narrator of extant drama.

We speak to a deeply troubled and troubling world, a world mindfully amnesiac on its voluminous inventory of madness, a world intent on ripping the sutures on history and populating the future with new scores that will seek settling. We speak to a world gone eyeless with hatred and rage yet again, a world fed by unresolved furies, a world that has refreshed biblical appetites for land and blood, a world whose shrill endorsement of prejudice, at once visceral and lofty, is even uglier than its abominable enactments.

We speak to a broken nation, a nation at the precipice of its unmaking. We speak to a future that we are not recognising as already our present; it is taking us in, layer upon layer, in ways that we must grasp if we are to be able to combat its consequences. We speak to flaming demagoguery and the emergence from its energies, the tableau of a cult that, by definition, seeks subscription and submission. We speak to the disabling of our institutions and to the enabling of crony monopolies. We speak to the repetition of lies — malevolent lies, constructed lies, deliberate lies; blatant, unembarrassed lies. We speak to echoes coming off the violated frontiers in Ladakh.

We speak to our ridden lives — to hunger and joblessness, to violent disruption and dislocation, to inspired and amplified fractures; we speak to a simmering disquiet over who is Indian and who is not, and how one shall be sorted from the other like rotten chaff from grain, our plurality tortured into homogeneity. We speak to majoritarian tides that, through ballots instigated by bigotry, seek to subvert our pious vow to the Constitution; to tides that seek to dismantle the Constitution itself. We speak to our imperilled freedoms, we speak to elected authority grabbing rights to turn authoritarian. We speak to such anxieties.

But we speak to much else, for humankind has also progressed this far keeping hope and goodness and cheer forever kindled. We speak to achievement and to triumph; we speak to optimism and to dreams. We speak to the irrepressible tendrils that bind us and keep us humane. There is a single word in Bangla that answers to the question what do you do: Sansar.

We speak, on that note, to a city like no other on this planet: Calcutta.

In the mid-1990s, when I first came to this city for a short work residency, I chanced upon one morning on the story of one Shahida Khatoon. She had become a mother before she could fully become a girl and, at 16, was dead before she could fully become a mother, consumed in a hospital ward by a crew of predators — anaemia, tuberculosis, jaundice and that most terrible killer of them all: poverty. In no other city would the death of Shahida Khatoon, pavement dweller, have made news. In Calcutta, she was on the front pages; the city gave her death its signature.

It had rained the morning she was reported lying at the gates of the Calcutta Municipal Corporation headquarters abutting New Market. She had been badly burnt, trying to save Jarmina, her infant daughter, from a stove flame. She was frail and lacerated, she was in urgent need of attention, and she had nowhere to go because she had no money. The old man walking up to the gates of the CMC in the steady drizzle that morning must have read of her in the morning’s newspapers and that spirit called Calcutta must have driven him out of home, umbrella in one hand, a few crumpled rupee notes in the other. It wasn’t a morning for hobbled old men to go out walking but this one was there, desperately seeking Shahida. Shahida wasn’t there. The rain had pushed her out into a bylane by the piggery on New Market’s north face. Her mother, Jubeda, was with her. A classic Calcutta moment awaited them. The intent old man located Shahida in the drizzle and came to stand by her cot, currency in his palm like crushed rose petals for offering; and Jubeda stood there grabbing the notes hurriedly and pushing them down her blouse, furtively ensuring nobody saw and loudly assuring that the money had gone to the right place. Poverty had extracted the price of its spectacle.

But there was another Calcutta moment unfolding, around the face of the old man with the umbrella and the palmful of rupees. He was no do-gooder chasing fame, he had not brought reporters and camera crews in tow; it was clear he intended to do what he had come to do with the minimum fuss. He was nobody trying to get donation rebates on his taxes; his chappals were torn and the rain had worsted them even more. Scarcely anybody noticed him arrive, give and leave. Before Jubeda could put away the money, the old man had become a walking umbrella among many walking umbrellas on Corporation Street.

In no other city would Shahida have died cared for and mourned as she was here. In no other city would they have had time for her. Calcutta has time for its dead, and a little bit of honour (if column inches in newspapers could mean that). Which is probably why life lives here.

Calcutta lives with its heart poured out onto the streets; nothing comes between people and their lives, not even the misery of poverty. Take a ride late night across Park Circus and Rajabazar or Kadapara. It might teach you that a life of joy does not necessarily have to do with money. Bathing under streetside gargoyles can be more fun than a burger parlour munch. Or just be in Calcutta during the Pujas. It is celebration and everybody celebrates. There is no toll on being festive, not yet. Calcutta is festive like no other city can be and the essence of it is that the beaten underside of Narkeldanga can be as, if not more, joyful and festive as Alipore or Ballygunge.

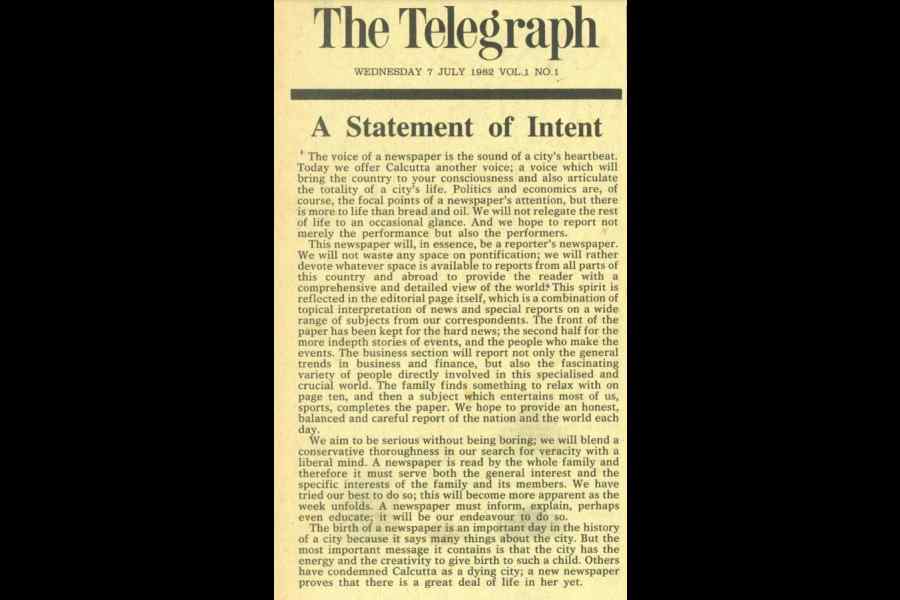

There is very little in Calcutta not to complain about. But there is very little Calcuttans complain about, perhaps because they are too busy living and making a life of it with a smile where there is so little to smile about. Shahida may be dead and a hundred others maybe dying but they are less inconsequential than they might have been elsewhere. This is no dying city. This is a city trying to live. And we are pledged, as the affixed “Statement of Intent” from the day of our birth says.

The renewal of the pledge to speak to you — as the affixed “Statement of Intent” from the day of our birth says — is, like the arrival of this newspaper at your doorstep, our daily rite.

sankarshan.thakur@abp.in