Khabar nahin is jug mein pal ki

Samajh mun! Ko jaane kal ki?

A moment’s meaning in this age no one can tell

Who then, O mind, can know the morrow? Ponder well!

Chapter 16 of Satyana Prayogo athava Atmakatha, Gandhi’s autobiography, contains this Hindi couplet, translated for me by the renowned scholar of Hindi and Braj Bhasha, Rupert Snell. The chapter itself is titled Ko Jaane Kal Ki.

In Mahadev Desai’s celebrated English version of the autobiography, An Autobiography or The Story of My Experiments with Truth, the chapter-heading is logically trans-titled “Man Proposes, God Disposes” but the verse itself has been dispensed with. This is a pity for, apart from being poetically compelling, it reflects a feeling that completely accords with Gandhi’s experience of life. As, I believe, it does with that of so many of us, constantly surprised as we are by the unexpected, notably by those most universal of occurrences which yet remain deeply traumatizing — illness and death.

There is another human condition on which the couplet fits neatly, political imponderables and the rule of law or, rather, the law of rules. Or, a perverse application of those. Gandhi’s autobiography, with that Chapter 16 heading “Ko Jaane Kal Ki” is among the most translated, with about 20 Indian language editions and some 30 plus in other languages of the world ranging from Swedish to Swahili, Tibetan to Turkish. In all the four of those language-societies, randomly selected here, “Ko jaane...” has applied, continues to apply. We have only to recall Olof Palme’s assassination in Stockholm, the capture and killing of Patrice Lumumba in the Congo, the exile of the Dalai Lama and the experience of only a few days ago, in Turkey, of Canan Kaftancioglu, sentenced to nine years and eight months for insulting the president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, to see that in all those, Gandhi’s “Ko jaane kal ki” is a real satya.

The book will continue to be translated. And, through that un-sourced couplet, will continue to tell us to always expect the unexpected. The first translation of Gandhi’s autobiography into Bangla by Anil Kumar Mitra uses, for the chapter-heading title, “Bhabi Ek, Hoy Ar”. And, like Desai, Mitra also drops the verse. Birendranath Guha’s Bangla version (Atmakatha: Satyer Prayog, Gandhi Smarak Nidhi, 1967) reproduces the original Hindi verse, but without translating it. Satish Chandra Dasgupta (Atmakatha athaba Satyer Prayog, Gandhi Satabarshiki Samiti, Calcutta, 1970), to his great credit, accesses the original Gujarati and retains the verse as well as its rhyme-form:

Paler thikana nai ei bhabe,

Bujho mon, ke jane kal ki habe!

Gandhi, who tried assiduously to learn Bangla until, and even on, his very last day in life, would have liked that translation and said, each time he was arrested, softly to himself or to Kasturba near him, Ke jane kal ki habe! He was arrested about ten times in South Africa and an equal number of times in India. On most of these occasions he was expecting or half-expecting to be apprehended. But on three occasions he was surprised by the timing of the moment, the ‘pal’, leading him, one can be sure, to the absurdity of taking the morrow or ‘kal’, for granted.

His first arrest came to him as no surprise. He had asked for it. Three articles of his in Young India, his brave and meticulously edited journal (of which this year — 2019 — is the centenary) were cited as evidence for his arrest and prosecution in 1922. Gandhi knew, when he wrote those articles, thereby summoning Indians to offer non-violent non-cooperation, that he was ‘playing with fire’. And so he was prepared for arrest, prosecution. When told, in the courtroom, that his campaign was inflaming the people against the government or, in other words, he was causing disaffection towards His Majesty’s Government, Gandhi pleaded guilty, as did Young India’s publisher, Shankerlal Banker. But something did come to him as a surprise even in that episode — not an unpleasant one: the judge, Robert S. Broomfield, saying to him from his high seat: “... [Y]ou are in a different category from any person I have ever tried or am likely to have to try... [But] it is my duty to judge you as a man subject to the law, who has by his own admission broken the law...” Another surprise was the severity of the sentence. Complete silence filled the packed courtroom as the judge prepared to announce it. A contemporary account says, “It was as if the birds and animals too were still and people had stopped breathing.” He awarded Gandhi six years in jail and Banker one year. As the judge left, people present wept and fell at Gandhi’s feet.

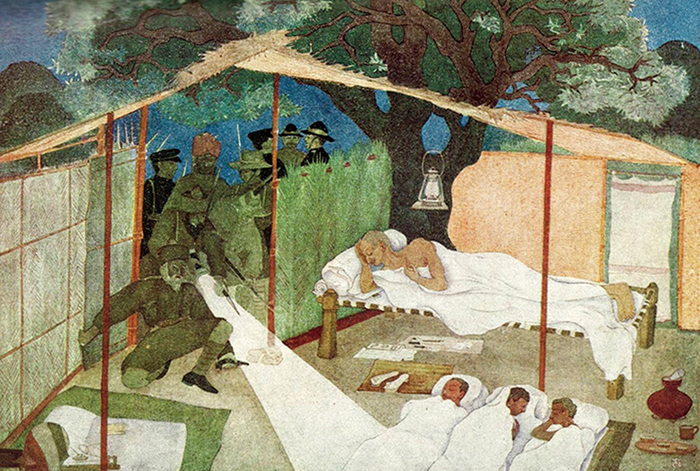

But two other arrests came before he was quite ready for them. Learning, perhaps, from the Ahmedabad experience, the raj did not want to give him the chance to make the moment of his arrest a point for national catharsis. It crept up to him on the hushed paws of a seasoned predator. His ‘midnight arrest’ in Karadi on May 4, 1930 following the Dandi satyagraha, from his camp in a hut in the village he was halting in that night has been described by Rajmohan Gandhi in his biography of Gandhi, Mohandas, thus: “About forty minutes after midnight, three officers (two British and an Indian), accompanied by between twenty and thirty rifle-carrying Indian policemen, entered the camp, walked quietly past marchers sleeping under stars and mango trees, and stepped inside Gandhi’s hut. By now sound asleep… Gandhi was woken up by lights flashed into his face. ‘Do you want me?’ Gandhi asked, even though he knew the answer...” Obtaining the officers’ nod to wash and brush his teeth (yes, they said, but be quick) he then asked his fellow marcher, the musicologist-singer, Pandit Narayan Moreshwar Khare, to sing “Vaishnava Jana” before being removed.

An unforgettable painting (picture) by Vinayak S. Masoji captures that arrest dramatically. Taken, first, in a lorry in total darkness, to a level-crossing, then by the Frontier Mail to an unscheduled halt just short of Bombay, then transferred to a Buick and whisked to Poona, Gandhi must have pondered well, Ko jaane kal ki... or Ke jane kal ki habe!

Not the arrest itself but the timing of it again came to him as a surprise in his last imprisoning in the pre-dawn hour of August 9, 1942 within hours of his call, “... freedom has to come not tomorrow but today... do or die...” Gandhi had thought the arrest would come but not before the viceroy, Lord Linlithgow, had granted him the appointment he had sought. But he was proved wrong. He was taken, with Mahadev Desai, to the Aga Khan Palace prison where Kasturba, also arrested for announcing her intention to speak at a rally in lieu of her arrested husband, joined them. Ke jane kal ki habe! was replayed to Gandhi and Kasturba when, six days after they had been locked up, on August 15, 1942, Mahadev Desai, just after having typed a letter from Gandhi to the viceroy, Lord Linlithgow, collapsed ‘just like that’ and died. “Mahadev! Mahadev!” Kasturba sobbed while Gandhi, bending over on the inert body said softly, “Mahadev... Mahadev... speak to me...” No reply. I knew that, Gandhi later said, I called him only because he never disobeyed me. Kasturba, already ill, could not survive her ailments compounded by the imprisoning and died on February 22, 1944. Mahadev and Kasturba, whose sesquicentennial also occurs this year along with her husband’s, were the kal that hides in each pal.

To the unforeseeables that each pal conceals we must now add the macabre reality of terrorism, as has been seen in site after blood-smeared site, and of the retaliations that can follow.

Ke jane kal ki habe! is not fatalism. It is not an intimation of death. It is an awareness of the value of each passing moment and its potential for a life in liberty.