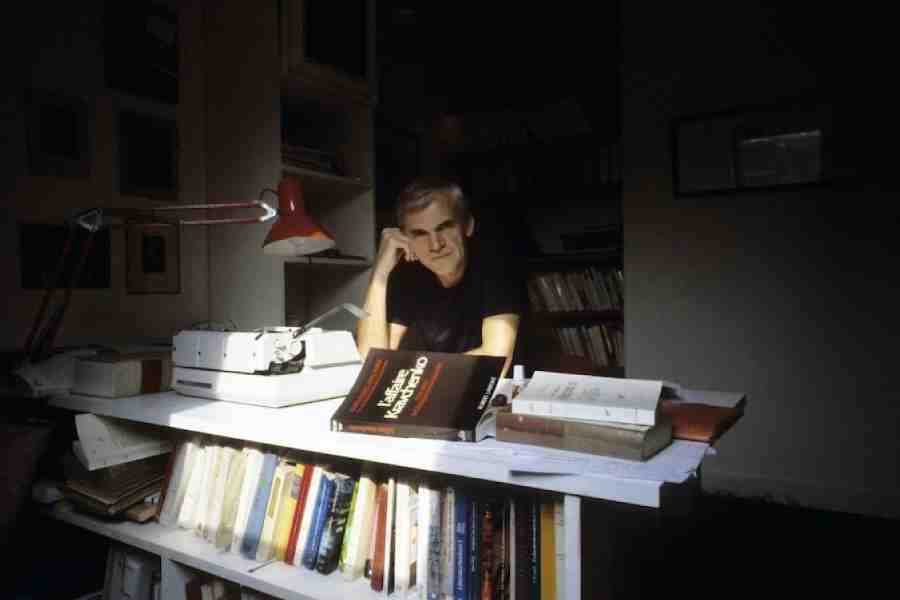

For anyone whose aesthetic sensibility included the unbearable heaviness of the Iron Curtain, or even the memory of it that was drawn out in Bengal till the end of communist rule in the state — the death of the Czech novelist, Milan Kundera (picture), was much larger than the demise of a person, or even that of an individual artist with an influential oeuvre. I don’t just mean the end of a looming reality, that of totalitarian rule, or the suppression of the freedom of speech, which has returned as a reality in India today. I mean the death of that mischief-making figure of speech. The death of irony.

Modernism evoked a real world of sensory, atmospheric details. Cleaved by the poststructuralist loss of faith in the power of language, postmodernist fiction felt it was futile to try to create a real world. Hence the metafictional, the spiky ironies, the advertising/copywriting lingo, the pastiche of commercial discourse. But for me, the disenchantment always felt tiring in Anglo-American writing, as opposed to the shockingly real invocation of this unreality in continental Europe. The dead serious playfulness of Kundera and Italo Calvino spoke to me, though I never had much appetite for Umberto Eco’s semiotic sleuthing. Literary taste is a bizarre thing. Pushing against oppression of one kind, Kundera created another kind in his fiction — the masculinist world of unsympathetically drawn women characters and relentless male philandering. The philandering Karel, in The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, meets Eva; together they plot a friendship between Eva and Karel’s wife, Marketa; taking the credit of introducing Eva to Karel, Marketa doesn’t know that Eva is already her husband’s lover. The best way to fool-proof an affair, the narrator implies, is to make sure that your mistress ‘enters’ your life as your wife’s friend, not yours. The pride of that discovery, and the trust in friendship, will insure you against the suspicion of infidelity for a long stretch. Irony glistens right in the heart of the fiction that plays such vicious double standards between the personal and the political.

In the tradition of the great European absurdists and existentialists, postmodernists like Kundera and Calvino evoked lightness and laughter in the face of political crises. “If the writer has an ideological goal, and he always has,” wrote the black South African writer, Njabulo Ndebele, in the last decade before the end of apartheid, “he has to reach that goal through a serious and inevitable confrontation with irony, and must earn his conclusions through the resulting sweat.” The artist bears that enhanced human vision which sees laughter in the grotesque, lightness in suffering, and complexities that rivet and seduce. The 20th century experienced the sharp modernisation of death, war, and mass-murder — their technologisation and bureaucratisation — from Adolf Eichmann’s filing cabinets to Robert Oppenheimer’s nuclear physics. It has pushed art to the limits of absurdity and irony as much as to that of lyrical lamentation — Franz Kafka and Samuel Beckett as much as the anguished cry of war poetry.

But the West has sought to keep irony to itself. When it comes to crises in the non-Western world, particularly after decolonisation, it has bared its appetite for trauma porn and poverty porn. Past the irreverence of the Rushdiesque national allegory, representations of the non-Western world in European languages can no longer afford irony, now again a Western privilege. Art and media reports now sharpen each other’s fetish for the spectacle of poverty and trauma. An Amazon review of a recent English novel about communal violence by an Indian-origin author says: “I’m glad I live in the United States.” Spectacular narratives of pain about alien parts of the world make the West feel better about itself. That fetish shapes the reception of writing from sub-Saharan Africa. The DIY instruction essay, “How to Write about Africa”, by the Kenyan writer, Binyavanga Wainaina, will evoke grotesque laughter for what I worry is a long time to come: “Describe, in detail, naked breasts (young, old, conservative, recently raped, big, small) or mutilated genitals, or enhanced genitals. Or any kind of genitals. And dead bodies. Or, better, naked dead bodies. And especially rotting naked dead bodies. Remember, any work you submit in which people look filthy and miserable will be referred to as the ‘real Africa’, and you want that on your dust jacket.” Forbidden are subjects that might resemble quotidian life, or anything resembling middle-class aspirations, because there is no such thing in Africa: “Taboo subjects: ordinary domestic scenes, love between Africans (unless a death is involved), references to African writers or intellectuals, mention of school-going children who are not suffering from yaws or Ebola fever or female genital mutilation.”

The storm of sarcasm that is Wainaina’s instruction manual is such a sharp slap on the metropolitan appetite for the spectacle of suffering that it remains ironic no longer. But the strategic selection of pain, abundant as it is in the Global South, is the Orientalism for liberal whiteness even today. No room here for the pervasive gray between the public and the private that makes the prime space for irony — the unpredictability of private response to public crisis. Artistic irony needs the freedom to be morally irresponsible, something which Milan Kundera enjoyed to the fullest, an abundance of which I found in a recently-translated bangla book, one not widely read even by Bengali readers — Entering the Maze: Queer Fiction of Krishnagopal Mallick, translated into English by Niladri Chatterjee. Mallick, who lived from 1936 to 2003, used truth as irony in his unabashedly erotic, often deeply autobiographical, fiction about personal growth — growing as much in one’s late fifties as in one’s teens. The unadorned truth about his homosexuality beyond his married life and fatherhood, his relentless cruising for sex in College Square, articulated in an idiom of childlike innocence, simmers in irony in the broad daylight of a deeply closeted bhadralok society. The sharpest irony is reserved for the phrase, “senior citizen”, in a story of that title. “On the last leg of the twentieth century, when the progressive world should be establishing a classless society, our government, and may be governments elsewhere too, pulled a back gear and created a new class — senior citizen — Thereby injecting divisiveness between the young and the old, between the son and the father, further poisoning the relationship by creating senior citizens as a privileged class.”

It is the class that doesn’t have to file tax returns, gets discounts on tram tickets and higher interests and incites jealousy from younger people. But Mallick is no saintly old man. He gropes private parts of attractive men in crowded buses, his efforts often appreciated and occasionally reciprocated. The day comes when a man appears in a bus, the “VIP Frenchie” commercial kind over whom ladies swoon, and Mallick does his thing. As they step off the bus, the man grabs Mallick’s throat and wrist and threatens violence, only to let him off “because you are a senior citizen.” Mallick, who called himself neither gay nor queer but by that old English name, homosexual, considered sexuality a private matter, not the political struggle it had already become during his lifetime. But unashamed about placing self-corroding irony between himself and the ideological, Mallick becomes an unlikely but deeply potent champion of queer consciousness today.

Saikat Majumdar is Professor of English and Creative Writing at Ashoka University